He didn’t say anything for a long time. I could see he was shaking but his eyes were obscured by shadows. He was breathing hard, or perhaps that was merely the rarefied, obsessive awareness of sound produced by the dark.

“Do you want to sleep?” he asked.

“It doesn’t matter.”

I was ashamed for not trying to disguise how tired I was. Red, green, a motorbike setting off and fading away. He sighed.

“Row with Irene. Violent. Nasty. In the letter I called her ‘sweet.’ Anyway … she’s leaving tomorrow.”

“Did you see Aurora?”

He whispered her name as if calling to her softly.

“I went to the hothouse, to her ‘island,’ as she calls it. She was there with a fair-haired man with very fine, almost feminine features, he was holding her hand, they were kissing. As soon as she saw me she came over, smiling. She didn’t seem to feel caught out. I wanted to explain things but she stopped me short by kissing my cheek. She introduced me to her friend, with a simple ‘Timoteo, my friend.’ And to him she said, ‘Antonio.’ She didn’t say anything resentful, behaved quite naturally, was sweet. It was as if an eternity had passed. I belonged to her past. I left pretty much right away. I looked back one last time, Aurora and her Timoteo gave me a friendly wave goodbye. And I knew I’d lost her.”

He put his glass on the table, near the Macintosh.

“Do you think she really loved me?”

I repressed a smile at this adolescent question. But what sort of answer could I give, as I know nothing about love, and never understand women better than on the day they leave me. He leaned with his back to the wall, against the nearly empty bookshelves. We stayed like that for a long time, not speaking.

I recognized the color of that silence. Years ago I spent three weeks in Inuit country, in Iqaluit and then Kugaaruk, far above the Arctic Circle. That was where I got the Reverend Samuel Wallis’s mask. Rather than staying in the Pelly Bay Inn, a hotel made of prefabricated units, I rented a room in a private home. My host was called Niam Amgoalik. In Inupiak, Niam means “sweetness” or “my darling” but, although he was welcoming enough, this man was not the image Europeans have of sweetness. One evening when Niam and I were in the living room — I was reading a copy of Nunatsiak News several months old and he was repairing the handlebar of his Skidoo — there was a knock at the door and a man came straight in without waiting for an answer. Niam didn’t say a word, just gave a friendly nod. The visitor took a Coke from his bag, opened it and sat slowly in an armchair. Niam carried on mending his handlebars while his friend sipped his Coke. It wasn’t completely silent: Niam breathed loudly as he tinkered with the brake lever, his friend burped from time to time, and I turned the pages of the newspaper. Outside there was the noise of a snowstorm, the smack of a badly secured shutter.

I eventually got used to this muteness and forgot my initial embarrassment. But while Niam and his friend were sharing the simple fact of being together, I was withdrawing into myself to the point of indifference. And when, after half an hour, or perhaps a little more, the friend waved goodbye to Niam and left, I felt incomplete, like a deaf person who has watched musicians play but heard nothing of the tune. I never knew Niam’s friend’s name.

A motorbike backfiring on the street broke the spell. Antonio knocked back the rest of his ouzo.

“Thanks, Vincent. I’ll go back to the hotel.”

But he didn’t move. The wall turned from red to green. I went over to the window and opened it wide, a breeze carrying the smell of the sea swept through the room.

“I think I have a couple beers, if you like.”

“Okay.”

I opened the fridge, and as I took the bottles out the cold neon light briefly illuminated the portrait of Duck. It was too late to hide it from Antonio.

“What the hell’s that, Vincent? It’s — it can’t be.”

He took out his wallet, searching through it feverishly.

“Yes, it’s Duck,” I preempted him. “I — drew it from memory. I thought she was beautiful. Her face is so … pure.”

Antonio found the photo and compared it to the portrait, speechless.

“I know I should have told you,” I went on, “but I never thought you’d end up seeing it.”

“But, Vincent, I don’t understand. You don’t know her, and this portrait … it’s not just a drawing.”

“I could give it to you, it doesn’t mean anything. It’s just a, what would you call it? Just an amateur sketch. I wanted to get back into working with charcoal. Since meeting Aurora.”

“You’re messing with me, Vincent … I think this is … sick. Kind of love by proxy.”

“What are you talking about? What love? Forgive the comparison, but Leonardo da Vinci wasn’t in love with Mona Lisa. It’s just a picture.”

I must have hit the right note because Antonio grimaced, then smiled properly.

“Okay. I’ll give you that. I should apologize. Let’s open these bottles.”

I prized the lids off and Antonio took one of the beers and walked over to the window. He looked at the portrait, more relaxed, appeased.

“It’s good, for something done from memory. It would have been even more faithful if you’d had the photo. You’ve aged her a bit, but she must actually look like that now.”

I didn’t mention the printers on the rua da Barroca but asked, “Wouldn’t you like to know?”

“No.”

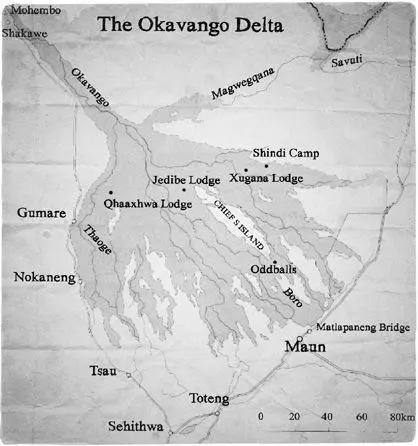

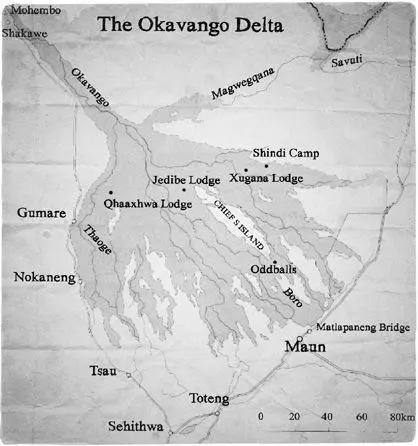

It was a cold no. I showed Antonio the map of the Okavango Delta.

“Do you remember Okavango in Botswana, Antonio? You took the pictures, I wrote the piece. You hired a small plane, flew over the delta and the Moremi Reserve … They were magnificent pictures.”

“That was a long time ago. I don’t know why you brought that up. Sorry, I’m tired, I’m going back.”

Antonio finished his beer, nodded, and left.

But no one forgets the Okavango. It’s an African river, a really long river, much more powerful than the Tagus or the Rhône and over half a mile wide at the Popa Falls. Its source is in Angola, it flows through Namibia before reaching Botswana. That’s where it meets the Kalahari Desert, where it coils into meanders, creating a rich tropical forest and producing a vast, swampy, saltwater delta that is home to tens of thousands of flamingoes. In the dry season, there are a myriad of islands formed around giant termite mounds and dense shrubs. Tourist leaflets describe luxuriant marshes, a miracle performed by water, an earthly paradise. All rivers run into the sea, yet the sea is not full, says Ecclesiastes. That’s not true: the Kalahari is vast and all the water of the Okavango gradually evaporates, or seeps into mud and sand.

The Okavango never reaches the sea. Its destiny as a river is never fulfilled. Of course other watercourses have the same fate: the Awash in the Afar region of Ethiopia simply irrigates that country’s great lakes, the Bear River ends its days in the brine of the Great Salt Lake. But no river is as powerful as the Okavango, none as indomitable. Its defeat in the face of the scorching Kalahari Desert is a catastrophe, its slow absorption like the end of the world. I’ve always liked old geographical maps, which is why I had bought the one I hung on the wall. That old map of the Okavango Basin was a metaphor for unfinished business, for adversity, for an unreachable goal.

I listened to Antonio walking along the deserted street. He suddenly started running and I heard the sound of his racing footsteps for a long time. Then the hubbub from farther down in the city smothered everything. I knew why Antonio was running. Sometimes the sound of our own footsteps becomes unbearable. It describes our impotence, our density, our weight. Walking means being resigned to that. So we refuse to be, and we run, it doesn’t matter where, because we’re running away from ourselves.

Читать дальше