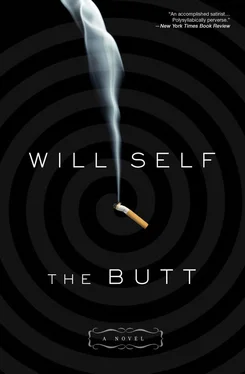

Prentice roused himself. The cigarette between his fingers had burned down. His waxy features had melted in the night-time heat. He was transfixed by Von Sasser, a feeble rodent pinioned by relentless talons. ‘Euch, no,’ he coughed, ‘we mustn’t forget them.’ Then he jerked upright and pushed his cigarette butt into the crowded ashtray.

A wild dog howled out in the desert, a cry that was taken up by others on all sides of the Tyrolean chalet. Tom thought: perhaps if I open the shutters there will be icing-sugar snow sparkling in the moon-light, a huddle of happy carollers under a cheery lantern. I fucked up in the dunes — but maybe he’s gonna give me a second chance?

‘The kiddies, yes. .’ the anthropologist mused enigmatically, and set his long pipe down at last. ‘They bring us back to where we started.’ The hollow eyes sucked in Tom and Prentice’s tacit assent. ‘We are in complete agreement, then: morality is always an instrumental affair. For the Anglo governments those instruments are the survey, the bell curve, and the statistician with no more imagination than this plastic fork.’ He held it up and deftly snapped off a single tine. This then became a diminutive baton, with which he conducted his own final remarks.

‘I spent a further decade acquiring the necessary skills needed to facilitate Papa’s conception of the good.’ The little baton swung in the direction of the scalpel case. ‘He had reached an impasse. He had cultivated these people, right enough — yet he had failed to harvest them. They still remained passively in the path of the Anglo combines. What was needed were mystics, firebrands and charismatics who would galvanize the embryonic body politic! Papa — who had no formal medical, let alone surgical, training himself — was relying on me to provide them.’

Von Sasser flexed the spillikin between his slim surgeon’s fingers; with a scarcely audible ‘ping’, a bit snapped off and hit the Consul’s forehead, then dropped to the tabletop. Adams stirred, groaned, drool looping from his slack mouth.

‘And that, gentlemen, is enough for one night.’ Von Sasser scraped back his chair and rose. ‘We will resume our discussions tomorrow. Very good!’

Discussions, Tom thought, was hardly the right word.

The anthropologist strafed the natives slumped against the wall with the tracer phonemes of his father’s made-up language. They got up — penitent, monkish in their black togas — and filed out. Swai-Phillips brought up the rear with his jazzy plainsong — ‘Oh, yes! The man, OK, the man — he’s said it all, he’s done it all. He’s the big sharp ’un. .’ which faded into the silvered negative of the starlit desert.

The Anglos’ exodus was a more awkward affair. Perversely, Adams, Loman and Gloria all chose to behave as if they had been lapping up their host’s every word. They took their time to say their grateful goodbyes, praising Von Sasser’s food, his drink, his conversation. But when they stumped across the veranda and stumbled down the steps, their sleep-cramped legs betrayed them.

Tom and Prentice followed on behind.

‘Until the morning, then.’ Von Sasser bade them goodnight from the top of the stairs. ‘There are some things I’d like the two of you, in particular, to see, yeah.’

Tom went to his swag in the classroom of the abandoned school, musing on how it was that, for so long as he was lecturing, Von Sasser’s accent was located in the Northern Hemisphere; yet as soon as he ceased, the squawking indigenous vowels came home to roost.

As he undressed, Tom admired the scissoring of his lean heat-tempered limbs. He slid into the canvas pouch and was soon asleep.

In the night, first one of his twins and then the second crawled in with him. Tom buried his face in their downy little backs. Later on, more disturbingly, Dixie joined them. Tom had to manouevre a twin in between them, lest he inadvertently press his groin against her thigh. Finally, shortly before dawn, Tommy Junior came into the classroom. ‘Where are you, Dad?’ he called out in the anaemic light. ‘Where are you?’

Tom wanted to respond to his adoptive son, but he was encumbered by the fleshy straitjacket of his own flesh. He could see Tommy Junior plainly enough, but the boy wasn’t helping himself. He refused — or was unable — to remove the hand-held games console from right in front of his eyes, so he bumped into the desks and collided with the walls.

He persisted, though: ‘Where are you, Dad? Where are you?’ His own wanderings in the maze of furniture replicated those of the tiny avatars on the screen he was fixated by.

Dixie, the succubus, rolled over and grasped Tom’s thigh between her own legs. It was she who had the impressive morning erection: a pestle that she ground into him. He screamed, but there was a rock rolled across his mouth, and the cry echoed only in the cave of his skull.

Between sleep and waking, paralysis and flight, myth and the prosaic, the existential and the universal, Tom watched, horrified, as Tommy Junior at last found a way through. He flopped forward on to the swag, and his adoptive siblings splattered into nothing. Now, there was only the overgrown cuckoo child bearing down on Tom, crushing the life out of him.

Tom ungummed his swollen lids. Gloria Swai-Phillips was sitting in a chair by the window. She wore a cotton dressing gown patterned with parrots, and her hair was wet from the shower. The sunlight flared on its damp sheen, but her face was deep in shadow.

‘You’re gonna haveta get your shit together today, yeah?’

Why, thought Tom, did no one in this country ever prefix their remarks with the verbal foreplay that made it possible for humans to rub along with each other? Every conversation was as brusque as a military briefing. He slid upright in the sweat-lubricated sheath of the swag.

‘I know that,’ he replied, groping underneath the mattress for the reassurance of the envelope with his tontine in it.

‘So long as you know, right?’

She stood and her gown fell open. Her pubis was bare but for a pubescent tuft. The mousetail of a tampon dangled from her cleft. She moved to the door in wifely déshabillé. I’m spotting, Tom. . and it’s your fault. .

As he dressed, Tom reflected on the previous evening. They were all — Adams, Gloria, Loman, the mentally ill Swai-Phillips — in thrall to Von Sasser. It was equally plain that the anthropologist thought little — if anything — of them. However, with Tom himself there was surely a shared bond: the matter of Prentice. Tom may have had a failure of nerve back in the dunes, but Von Sasser’s manner towards him suggested that this need not affect the current situation. The important thing was to act. ‘I am the Swift One,’ Tom said aloud as he splashed brownish water on to his tanned face. ‘I am the Righter of Wrongs.’

Breakfast was already under way. Last night’s company were seated at a long trestle table that had been set up on the veranda of Von Sasser’s chalet. An awning protected them from the fierce sun. There were thermos jugs of milk and coffee, cartons of juice and cereal boxes dotting the tabletop; among these were salvers heaped with the scary fruit that Tom remembered from the Mimosa.

‘See, Brian,’ he said bumptiously to Prentice, who was nursing his hangover with a can of Coke. ‘Aluminium bowls and aluminium cans — even the Intwennyfortee mob can’t do without Eyre’s Pit, so no need for you to become a bleeding heart after all.’

The long night of serious schnapps-drinking had paradoxically agreed with Tom. It occurred to him, as he munched his Rice Krispies, that this might have been because of the small quantity of gasoline Von Sasser put in the spirit: maybe I was running on empty after all that damn driving and just needed to refuel.

Читать дальше