The man turned red-veined engwegge eyes towards Tom; his face was masked with indifference. ‘Gas,’ he clicked. ‘Then road block. Only gas fer a thousan’ klicks — plenny road blocks.’

He snorted derisively, then spat a stream of brown juice through the window on to the rusty roadway.

The motel was a blockhouse of blue-grey cinder-blocks with a corrugated-iron roof. It looked like a latrine built by intelligent horses. Each of the stall doors was equipped with a coin-operated lock, into which the ‘guest’ was obliged to feed twenty dollar-pieces in order to obtain his key. There were no staff in evidence.

Tom, having left Prentice at the wheel of the car with strict instructions to pull forward if the line moved — ‘No matter what your degree of fucking astande is’ — now worked his way back along the scores of stalled vehicles, gathering the required change as he went.

Most of the drivers were indifferent to his plea. They sat in their hot boxes, oblivious to the flies dancing on their faces, and listening — Anglos, Tugganarong and natives alike — to the radio commentary on the same interminable sports fixture that Prentice was obsessed by.

As he moved from fan to fan, Tom gathered that this was being played at the Capital City Oval, between the national side and a team from Prentice’s homeland. The commentators spewed the usual trivia, but Tom did learn — with considerable pleasure — that Prentice’s team were losing by many points.

This explained the sulky expression on his face when Tom eventually rejoined him. Tom dumped the forty bucks’ worth of coin into his cupped hands.

‘Go along to the motel and check us in,’ he ordered. ‘You can at least do that, can’t you?’

Prentice stubbed his cigarette out in the car ashtray with unnecessary violence. ‘Only so long as I don’t have to carry anything, Brodzinski.’

‘Anything?’

‘Anything.’ Then Prentice tried to be emollient; it didn’t suit him. ‘Look, y’know I don’t hold with this bing-bong rubbish, but I feel, well, forced to obey it. And. .’ He turned in his seat, eyes flicking to the boxes of medical supplies. ‘Well, if I don’t get this stuff to the Tontines, things could go very badly for me.’

It was the first time Prentice had referred directly to his own crime. Tom again felt the urge arise to force the foul man to reveal exactly what he had done. He pictured a summary execution out in the desert sunset: Prentice kneeling beside a shallow grave he had, in a break with taboo, dug himself. His face was a study in contrition; ‘Goodbye, old chap,’ he was saying. ‘Sorry for any inconvenience I may’ve caused you. .’

‘Whatever.’ Tom snapped back to the present. ‘I’ll wait here; if we don’t fill up with gas now, things will go badly for both of us.’

The sun swelled, grew darker, its ripe bulk squashed against the horizon. The stony bled, so unlovely in full daylight, transited rapidly through a bewildering succession of poignant shades: roseate red, early-spring violet, silvery-grey — until night empurpled the gigantic mesas in the far distance, and bunches of stars dangled down from the empyrean.

The gas line had barely moved.

Prentice’s game had long since been abandoned for the night, and the radio station had ceased transmission soon afterwards. Tom twiddled the dial, but he could find no other. They sat, not talking, and Tom ruminated: would it go as Swai-Phillips had suggested? Once the rifles, the cooking pots and the cash had been delivered, would the constipated legal process back in Vance loosen up? Maybe he would be at home in Milford in time for Thanksgiving. The candles modelled like effigies of the Pilgrim Fathers would be burning on the sideboard in the dining room, wax dripping from the brims of their black hats.

‘Look,’ Tom said eventually, ‘I gotta get some sleep. I’m gonna drive the car off the road a ways, then we can take the valuable stuff and head for the motel. We’ll have to get the gas in the morning.’

‘Are you sure that’s wise, old chap?’

Tom was only grateful he couldn’t see Prentice’s superior expression, and the idiotic lappet of his dyed hair. Tom turned the key in the ignition and pulled off Route 1. With headlights off, they bumped a few hundred yards into the desert. Then, humping the rifles, their ammunition and the boxes of Prentice’s ribavirin and amoxycillin, Tom followed him towards the blazing lights of the road stop.

Later, they stood at the motel’s sixteen-metre line while Prentice smoked and Tom applied the ointment to his psoriasis.

‘The hot springs seem to’ve cleared this up,’ he said. Then, hating his own note of wifely concern, he added: ‘You should’ve stayed there.’

Prentice only grunted.

They were both tired and hungry. There was no hot food available, except for meat pies from the gas station: sad pastry sacks containing a disgusting purée of minced meat and potato. Even Prentice hadn’t been able to finish his.

Besides, rank exhaust and gasoline fumes hung over the whole area, while the heavily armed paramilitary police manning the checkpoint introduced a nervy tension to the soiled atmosphere.

‘I’m gonna bunk down,’ Tom said, and handed Prentice the tube of ointment.

For a few seconds the macho remark sustained him, then Tom found himself alone in the neon light of his rental cubicle, with its blue insecutor fizzing and popping as the night bugs committed unpremeditated self-murder.

Tom woke in the utter darkness. He could hear the wheezing and trickling of the aircon’, a generator pounded, a helicopter chattered overhead. He had fallen asleep reading the Von Sassers, and the weighty tome still sat on his chest, pinning him down, a somnolent lover spent by coitus. Shreds of dream whirled behind his eyes. He had been reading of the engwegge ceremony before he slept: how the women chewed the seared shoots, then passed the wad from their mouths to those of the men. He had dreamed of Gloria doing the same to him, her assiduous tongue pushing the bitter cud.

Tom groped for the cord and yanked it. The tube flickered, then slammed the cinder-block walls, the concrete floor and the rifles propped in the corner into stagy existence. The Gloria succubus flew towards the insecutor, then fizzed and popped out of the playlet. Tom groped for the bottle of mineral water and drank deep of its warm, brackish contents. He felt like a cigarette; felt that deep and visceral need for nicotine that had long been absent. Felt it as if it were a banal mode of lust.

Outside the arc lights blazed down on the checkpoint. The long gas line had evaporated, and the only vehicles Tom could see were a couple of police half-tracks parked in front of the steel bar lowered across Route 1.

He wandered on to the garage forecourt. Behind the plate-glass windows a clerk was sitting by the cash register, drinking a can of Coke. It could have been somewhere on the outskirts of Tom’s own home town — the building was that international, that dull. The oval sign bearing the corporation’s logo was an a priori category: this was how creatures like Tom viewed the world.

He found himself inside, fondling the crackling balloon of a bag of potato chips. The clerk looked up at the sound.

‘Forty Greens,’ Tom said.

The clerk pulled an ectomorphic pack from the rack. ‘We only got fifties, mate,’ he explained, holding it aloft.

Tom pulled limp bills from his jeans pocket. Together with the cigarettes he received a promotional lighter with the legend EYRE’S PIT: EXPERIENCE THE DEPTHS OF PROFUNDITY printed on it.

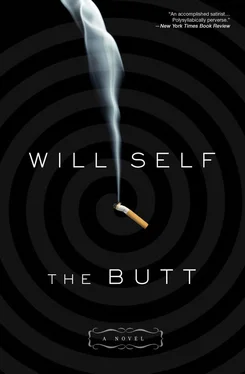

Back in the night, Tom stalked to the edge of the forecourt, then took sixteen careful paces. Peering at the gravel between his boots, he could make out the expected line of butts, tidal wrack left behind by the great perturbation of human need, its empty troughs and satiated peaks.

Читать дальше