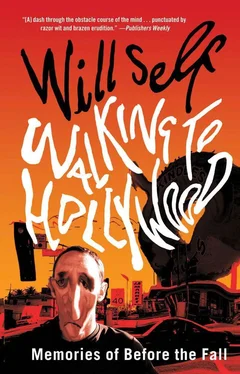

Will Self - Walking to Hollywood

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Will Self - Walking to Hollywood» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Grove/Atlantic, Inc., Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Walking to Hollywood

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Walking to Hollywood: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Walking to Hollywood»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Walking to Hollywood — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Walking to Hollywood», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The sixth impression of a Fontana paperback published in 1972, I had read it in this very edition, concurrently with my father, when we were rained in during a Cornish walking tour. Can there ever have been anywhere more subdued than that parlour, with its carriage clock’s gold-balled gimbals slowrevolving on the mantelpiece, and the superfluity of Windsor and wing chairs? We had lingered over breakfast as long as we could, my father, as was his way, elaborately buttering a single, mouthful-sized section of toast, then anointing it with marmalade, before finally and reverently consuming it. The rain lulled outside gathering its strength, then gushed. My father went out to negotiate with the lady of the house — we were permitted to stay but confined to the parlour, where we sat all that long day, either side of an electric fire, its bars furry with summer dust, and read alternate chapters of the Christie, the contest being — with my father there always had to be competition — to see who could guess the murderer first.

Night fell with the rain. A flyer in the bus shelter promised a choral performance at the village hall. We sallied out along oilskin roads from Trebetherick to Rock. I was so bored by then that even the red-faced farmer’s wives belting out Handel pleased me, while as for my dad—

‘These might interest you.’

‘I’m sorry’.

‘These may interest you — these here.’

The Elastoplast he had wrapped around the bridge of his spectacles fitted precisely in the groove of his frown. His eyes — of an awesome mildness — held me as he leant forward over the counter. At the base of the triangle formed by his forearms, between the heels of his liver-spotted hands, were five wood carvings of etiolated human figures. They were perhaps a foot to eighteen inches long and lay in a pile like outsized spillikins. There was also a larger piece of wood: one end curved into a stern, while the prow had been whittled into a serpent’s streamlined head. There were also three discs that, if shields, were to scale with the figures. To one side lay a little heap of what looked like spare limbs — or possibly clubs.

The man wearing the corduroy cap had gone. Outside the lunchtime shoppers had evaporated, while in front of the newsagent opposite a handwritten shout for the Hornsea Echo lamented: THREE SISTERS DISAPPEAR IN BEWHOLME. ‘Pick one up,’ the shopkeeper ordered me. ‘D’you recognize it?’

Fragments of quartzite had been rammed into the figure’s roughly carved pinhead, a head reduced by bronze blade to its essential planes: a sharp chin, a triangular nose, the oval slot of a mouth. It lay on its back in my palm. The wood was warm to the touch, fine-fissured pine. I hefted the figurine — it was perfectly balanced, more like a tool than anything decorative. I guessed it must be very old, although the neoteny of the head, the armless shoulder sockets, the notched crotch and legs that tapered to a point also called to mind wavering aliens silhouetted in the molten light spilling from the cracked shell of a flying saucer.

I gingerly set the figure down on the counter and said, ‘I think I’d remember that .’

Then I was sitting on the seawall watching the tide lap back from muddy shingle. The wall was in three smooth tiers, with orange-painted steel gates set on mammoth hinges in the uppermost one. The sunlight was bright enough to strike sparks on the wavelets, yet overall visibility was only a couple of hundred yards, the sea mist enclosing what might be — for all I knew — an isolated section of coral reef. I peered closely at the smooth whiteness between my thighs — was it concrete, or the massively compacted exoskeletons of myriad antediluvian crustaceans?

I was getting out my oat cakes and the sweating cheese I’d bought in Skipsea, when a family came trundling out of the mist and sat right beside me. There was a chocolate-smeared three-year-old in a pushchair, its feet trailing along the path. Too bloody big for it, I thought, it’ll end up fat as its mother — who was mountainous in a bright red blouse and black slacks. A sixtyish mother-in-law was in attendance, her senior hair set hard. Her hovering around the pushchair was a mute agony: she mustn’t interfere , although everything her daughter-in-law did was wrong as wrong could be .

A short way off, on the steel stairway down to the strand, a skinny husband in a bowling shirt fiddled with a tacky kite. The six-year-old boy pestering him was equally skinny — all bone struts, stringy tendons and plastic skin. I watched them get tangled up in each other, while I removed from my rucksack my tea-making kit, a paperback thriller and a small oilcloth bundle, which when I unrolled it contained what appeared to be the detachable wooden penises of some Bronze Age figurines.

‘D’you want yer bap now?’ The mountainous mummy thrust the white roll at the child in the pushchair.

‘I thought, maybe—’ the mother-in-law ventured, then was silenced by a furious glare.

‘Go on, ’ave yer bap now!’ the mother insisted, kneading love and hatred together.

‘Ah, well,’ the mother-in-law sighed.

‘Whaddya mean by that?’ the mother snapped, and as the mother-in-law quailed I thought it will always be thus, until one or the other of them dies.

I couldn’t remember acquiring the Agatha Christie or the bundle of wooden penises. I knew that on my holiday I had taken with me a formerly lascivious madman, a neurofibrillary tangle, a pig-headed rubber figurine and a dead porpoise rescued from the long fetch of the German Ocean — but these?

While I was playing the memory game the skinny husband came up to get his own bap, abandoning the older kid to crunch along the shingle, the kite nipping at his heels.

‘Oh, it’s you,’ the man said when he saw me. ‘What’re you doing up this way again?’

I was grateful to him for two things: first, his bowling shirt, which was lilac with a blue revere collar, cuffs and pocket-facing; it was also monogrammed ‘Derek’ across the breast pocket. Secondly, there was Derek’s low-key reaction to what I assumed must be a quite a coincidence. I imagined he was responding intuitively to my blank expression, and fed me this easy question so I could skirt whatever mutual history we had, leaving it for him to unearth later.

I began explaining that I was taking a few days out to walk the Holderness coast, but no sooner had I begun talking than Derek interrupted me, turning to the uncongenial woman-mountain and blurting, ‘Look, it’s ’im who came round that evening we ’ad the bees.’

‘Oh, ho!’ she laughed. ‘It’s you — I didn’t even notice you sitting there all quiet, like. ’Ow yer doin’? Still writing your cra-azy books?’

Her sudden warmth was overpowering — I thought, how sad she has so little of this for her own, and also for an instant — could I spill it all out? My deteriorating memory — the quixotic quest for the man in the scrap of photograph I’d found in the gutter of St Rule Street? Might I throw myself on the soft mercy of her bosom?

‘It weren’t ’til well after midnight that the police got hold of some feller who knew how to deal wi’ it,’ Derek was saying.

In the course of a few more exchanges I gathered this: that he had gone to see me give a book reading at the Pave Café in Hull the previous summer. She — Karen, that is — would’ve gone too, were it not for a swarm of bees that had blanketed the front of the house: ‘The babysitter were absolutely bloody terrified.’ I, however, had risen to the challenge, and when I heard the tale accompanied Derek home and gave an impromptu recital in the kitchen, ‘While me an’ my mate drank oor gin.’

As this was transpiring the mother-in-law, released from her daughter-in-law’s cage of contempt, escaped with the pushchair. Wheeling it twenty yards off, she snatched back the child’s bap and began vigorously to wipe the chocolate from its mouth with an index finger cowled in saliva-dampened cloth.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Walking to Hollywood»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Walking to Hollywood» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Walking to Hollywood» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.