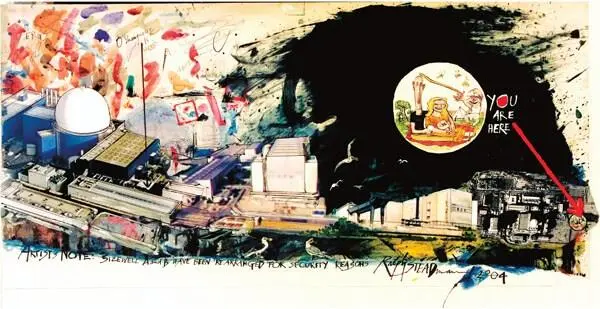

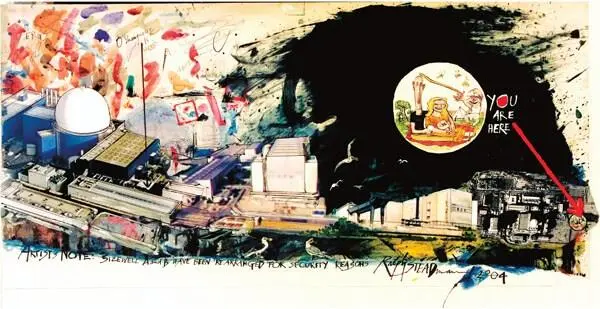

The two power stations — ‘A’, a humungous, four-square chunk of 1960s concrete, complete with outsize transom windows; ‘B’, a 1980s plinth of dark, yet iridescent blue steel, topped off by a vast golf ball of a dome — squat in back of the dunes, willing you to impose your own imaginative vision on them. I think the Supreme Ruler of the Entire Known Universe will probably take a lease on ‘B’ some time in the future, furnishing it with 100-metre-long smoked glass coffee tables and square hectares of quarry tiling. ‘A’ will become a charmingly recherché guest annexe.

The interzone between the fortified plutonium piles and the sea has been landscaped since I was last here, dinky hillocks skilfully mounded by British Nuclear Fuels, then planted with reed, furze and alien-flesh samphire. But off shore the two iron platforms which mark the intake and outflow of the power stations’ cooling system remain, streaked with rust and guano, capped by wheeling gulls. This plot of water is a few degrees warmer than the surrounding North Sea, so it attracts fish, fowl and fishermen, links in a strange food chain. The fishermen come mostly from the Midlands. Having headed in large numbers due east across country, as if summoned by some collective, phylogenetic impulse, they erect their little nylon huts on the beach. Here they sit until dawn, dabbling their lines in the Roentgen briny, sucking on filter tips and cans of Stella Artois, a peculiar temporary settlement of moody anchorites.

The beach has a visitor car park and a prefab tea shop dubbed, appropriately enough, Sizewell ‘T’; while drawn up on the shingle is the fag end of a centuries-old inshore fishing fleet, clinker-built and tar-caulked; but neither industry nor leisure can truly impose itself on Sizewell, where the collision between crumbling coastline and a human artefact with a guaranteed lethal half-life of tens of thousands of years induces a sense of exhilarating queasiness: deep time interpenetrating every grain of sand.

The small boys demanded an isolated camping spot, so their mother and I hauled our mishmash of equipment out along the beach, to where the BNFL land marches with the Minsmere Nature Reserve. Here, in a thicket of dwarf oaks, we erected our two-person tent. The campsite was soon invaded by many tens of hover flies, attracted by the gaudy flysheet. These curiously attractive insects looked like smallish bees redesigned by a contemporary jeweller: their flattened, angular abdomens had jagged markings, their compound eyes a grey sheen. Later, when we hit the beach, we found a positive wrack of them, lying dead above the tide line.

Darkness fell and the obligatory sausages were eaten, then it was back to the beach for a bonfire. The Matriarch pulled this off in fine style, arranging driftwood against a half-buried concrete dragon’s tooth with an artistry that would’ve caused Richard Long to tear his own heart out with envy and throw it, still beating, to the ground. The oily spars burnt green and purple, the slack waves rattled the shingle; we were snug in a little sitting room carved out of the soft night.

The following afternoon, heading back to the Great Wen, I turned the car off the road on to a track. I wanted to see a house that I remembered from ten years before. A perfectly nice dyad of farm labourers’ cottages, remarkable only in that they are tucked up in a dell within a hundred metres of the fizzing, popping hank of power lines that loop from the power stations to the first of the pylons, then march, seriatim, across the flat lands in the direction of Ipswich.

A decade before the house was untenanted, and it was difficult to imagine who would want to reside in this potential cancer risk; but now there was a young, well-spoken man, tinkering with an immaculate vintage motorcycle in the garage. We chatted a bit, and he laughingly acknowledged the preposterous character of the dwelling. Our six-year-old, sensing a toehold, chimed up from the back seat: ‘Excuse me, when we come back here again, can we visit your house properly?’ Sizewell, again.

In the early medieval period the lives of countless peasants were defined by their relation to the castle. From the stern keep of the Norman overlord issued forth decrees and exactions; in a world of wood, wheat and water, its high stone walls were the most adamantine confirmation of the temporal order, just as the acuminate spire of the church pricked the oppressive heavens. Writing, then, as a descendant of peasants, it seems only meet that I should testify to the manner in which my own life has revolved around and been shaped by the lineal descendant of these bastions. I refer, of course, to the bouncy castle.

I first went on a bouncy castle in the early 1960s. It was a wholly enclosed, striped, latex structure positioned on Brighton’s West Pier. Moon-walking around its interior, which whined with the ultrasonic echoes of other screeching children, I felt oddly empowered, ready to leap in my stockinged feet through some mystic portal and into the very future itself. How right I was. It seems to me that, throughout the seventies, eighties and nineties as the influence of Windsor Castle has waned so that of the bouncy castle has waxed. Could the two phenomena by any chance be related? After all, it’s impossible to retain any faith in the monarchical principle if you’ve grown up leaping around on a rubber simulacrum of their hallowed halls.

In 1980 I got a vacation job for the old Greater London Council’s Recreation Department. Together with a handful of other bohemian types I was responsible for the ‘inflatable project’. This involved constructing freeform inflatable structures and then transporting them around London parks during the school holidays. In charge of the inflatables was James, a one-time organiser — together with Brian Eno — of the Portsmouth Sinfonia. This avant-garde ensemble comprised scores of unlearned instrumentalists who would gather together to hack spontaneously — and unmercifully — away at classical music standards. The Sinfonia had a top thirty hit in September of 1981 with their ‘Classical Muddly’ — I was much impressed.

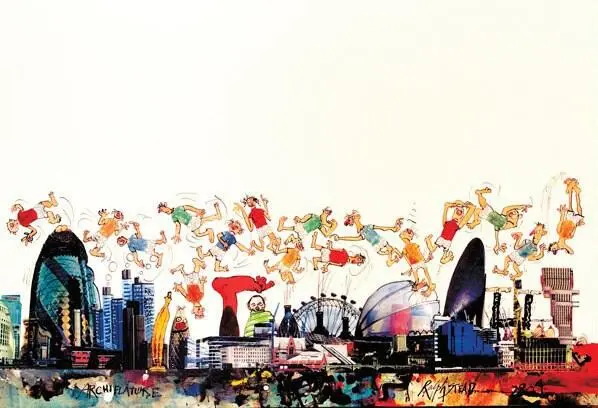

James, who also tutored at the Slade, brought a certain brio to the construction of bouncy castles. There was ‘the Child Psychologist’s Nightmare’, a bizarre maze of black and red tubes; ‘the Big H’, which was just that; and there were assorted giant spheres and rhomboids which we, the soi-disant ‘playleaders’, could climb inside and be pushed about by hundreds of squealing kids. I tell you it was a fine sight when all the blowers were working properly and some urban veldt was scattered with these Pantagruelian playthings. We would get anything up to five hundred kids a session, supervised by just four adults; and often, when ten or so sprogs leapt on to the crosspiece of the ‘H’, another forty would be thrown high into the air off its uprights. None of the structures was enclosed and yet injuries were far from common.

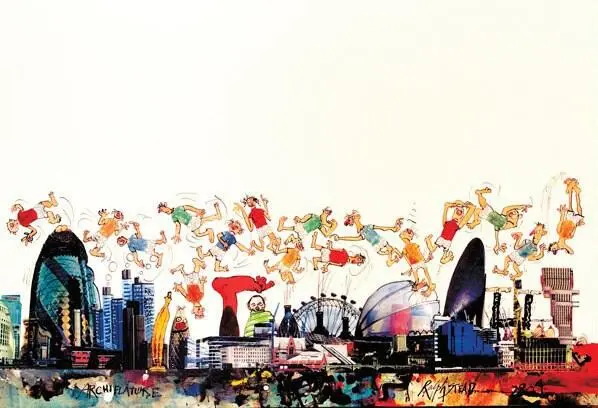

In those days the GLC had suzerainty over a number of open spaces unincorporated by the London boroughs. These were scattered as far afield as Thamesmead in the east, Eltham in the deep south, Shepherd’s Bush in the west and Alexandra Park in the north. So it was that I came to an adult consciousness of the geography of my natal city through the praxis of bouncy castles. For me London is neither the moneyed bulk of the City nor the bright lights of the West End; rather, it is an endless realm of boating lakes, bowling greens, football pitches and adventure playgrounds, all scarified by the summer heat and populated by a strange race of yammering gnomes, their faces coated with sucrose.

Читать дальше