Empty sky, flat sea, sharp wind. The occasional lonely walker, head bowed to escape the oppression of the sky. If I felt alone in the echoing precincts of the city, I now feel completely abandoned. On the outskirts of Hoylake a fat middle manager sleeps off his expense account pub lunch slumped in his Ford Omega, while I take a piss in a public toilet acrid with fresh saltwater and ancient urine. I thought I might walk from the point across to the tidal island of Hilbre, there to commune with seals, but in the event my timing is wrong, so I cycle to the station, fold the bike up and take the train back into the centre.

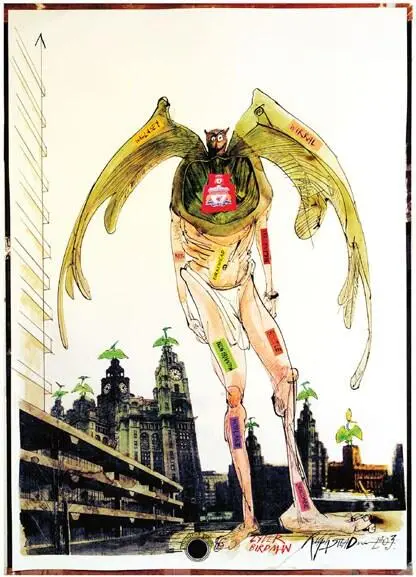

At Birkenhead we descend clanking into the tunnel under the Mersey, and suddenly all is echoing expanses of white tiling, festoons of cabling, and glimpses of tortuous machinery which suggest the nightmare visions of Piranesi. Intended for a far larger population, the superb local rail system of Merseyside is housed in caverns beneath the city itself, a ghost train endlessly circumnavigating the interior of this dark star of urbanity. But as if these tunnels, and the Queensway road tunnel under the river, weren’t enough of a vermiculation, in the last few years a group of enthusiastic volunteers have been opening up the Williamson tunnels. These brick-lined conduits were built by a local magnate during the early decades of the nineteenth century. Some say they were a labour-creating project, a piece of proto-Keynesianism, intended to provide employment for soldiers returned from the Napoleonic Wars. Others aver that Williamson himself was a millenarian, and that the tunnels were intended as a refuge for Liverpudlians from the coming apocalypse.

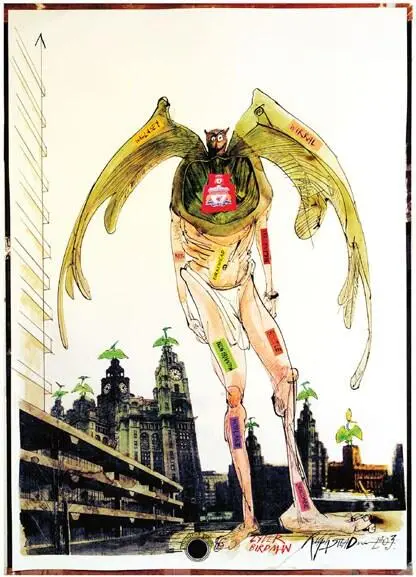

If the tunnels’ genesis is in dispute, then so is their extent. Some claim there are only a few hundred metres of them, but others swear that the whole fabric of the city is riddled like a vast Emmental cheese. Whatever the truth of the matter, the tunnels are a curious complement to the depopulation of Liverpool, an introjection of the municipality’s own sense of its emptiness; after all, if so many people have vanished, where can they possibly have gone to?

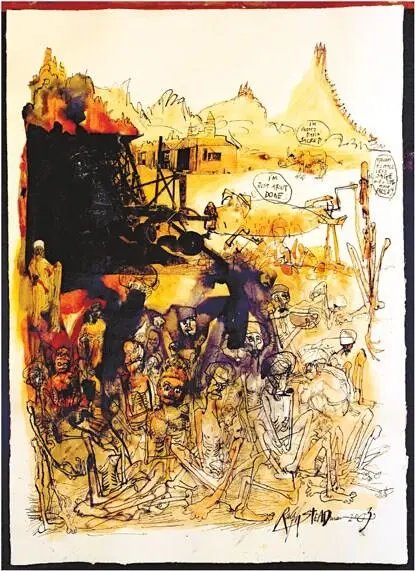

I arrived in Varanasi by minibus, a stubby little eight-seater which clumped and bumped along the straight and rutted roads of Uttar Pradesh from the Nepalese border. It took three interminable and baking days, days I spent sitting opposite an Australian hippy wearing a Victorian nightdress. Having no humanity or fellow feeling whatsoever, he read aloud from Shakespeare’s sonnets the whole way. I’ll never compare anyone to a summer’s day as long as I live, not after that.

Other passengers included a family of diminutive Indians. The pocket paterfamilias wore a white shirt, string vest, pressed trousers and shined shoes; the mini-matriarch was sandalwood-scented in a silk sari; the young princeling sported an Aertex shirt, grey shorts and school sandals. They never seemed to sweat, this family; the flies never alighted on them. They took chapattis from one Tupperware box and scooped up dahl from another, yet no grease was left on their nimble fingers. Were they perhaps — I idly considered — coated in transparent Teflon?

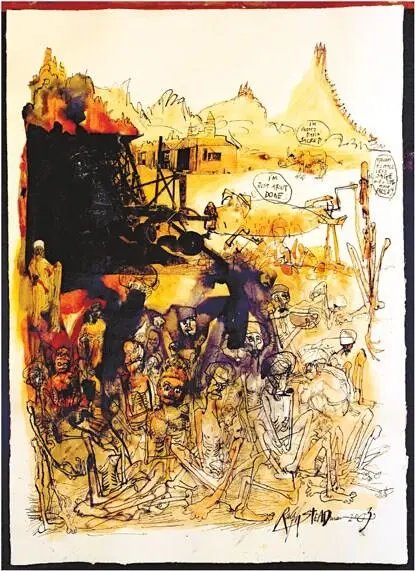

The nights we spent in wayside caravanserai, where I sweated and boinged on unstrung charpoys. Grey dawn would find me as fatalistic as any native, and shamelessly shitting at the side of a field. The landscape was so unfinished and yet so used up, like a vast kitchen in which no one had troubled to do the washing up for several millennia. By the time we reached the Holy City I’d just about had enough of travelling. I booked into the government Tourist Bungalow and took to my bed. The room was an upended stone shoebox with nothing in it besides a mattress and a bare light bulb. Outside there was an ox park. All day long an Untouchable woman scraped up the dung and mounded it into a compact ziggurat which abutted the exterior wall of my room. When night came she lay down on top of it and we slept within arm’s reach of one another.

After three supine days I ventured out. I’d met an excitable Ukrainian while sucking on bottles of Stag Ale in the Bungalow’s restaurant. He told me that he was in exile; his father — a high Soviet official — had sent him abroad to escape military service in Afghanistan. He believed in every conspiracy theory going: the Jews controlled the US and the USSR, while being controlled themselves by Venutians whose spacecraft was moored in the Bermuda Triangle. You could spot the aliens, he said, by their propensity for baldness and driving convertible Mercedes. On his old rucksack the wandering anti-Semite had the names of every country he’d visited, from Swaziland to Switzerland, crudely inscribed in ballpoint pen.

We went to the railway station so that I could buy a ticket for the Himigiri — Howrah Express, a mighty Aryan iron horse that would drag me clear across the north of the subcontinent to Chandigarh. I got a chitty from Window A and took it for authorisation to Window B. At Window B I received a second chitty and took it to the Sales Booth. Every single step had to be taken through a dense thicket of humanity; thorny limbs pricked me, twiggy fingers scratched me. I emerged blinking and bedevilled into the harsh light of the maidan. The Ukrainian examined my ticket and pointed out that I’d mistakenly bought one for the service which departed in eight days’ time, rather than on the morrow. I considered the hourlong battle that would be required to change the ticket, and, taking my lead from the ideas of astrological propitiousness embodied in Indian culture, rather than the cult of horological precipitateness enshrined in my own, I determined to stay the extra seven days in the Holy City.

Another kulfi-headache dawn. I’d linked up with a Canadian Buddhist — the very worst kind. He propped me on the handlebars of his Supercomet bike and pedalled us both down to the bathing ghats. Downriver I could see smoke rising from the death barbecue: long pig griddling for breakfast. The Buddhist knelt and prayed angrily, while I shared a chillum with a crusty sadhu. There was grit in the air, grit on my eyes, grit in my retinal afterimages. The terracing of temples and shrines, the lapping brown limbs of the goddess Ganga — for some hazy, hashy reason it all reminded me of Brighton. So it seemed like a perfectly logical step to strip, wind a lungi around my snaky hips, and descend into the natal flow. Halfway across I collided with the corpse of a cow, which, bloated to four times its life size, revolved slowly in the viral current. I spluttered, coughed, and went under while ingurgitating spirochaetes to last me a lifetime.

All this happened twenty years ago and I’d like to say that it seems like yesterday, but it doesn’t: it seems like twenty years ago. Now I’m an older, less adventurous and less stoned man. Nowadays I would change my ticket. Although, come to think of it, since my ultimate destination was Kashmir, I probably wouldn’t be travelling there at all. The past is another country — and the frontier is always closed.

Slogging up through the woods and on to the main ridge of the Chilterns on a damp morning in late autumn, the joys of summer rambles seem long departed. Ah! If only I could recapture that fearless rapture with which I turned the golden key, wrenched open the door and ran laughing down the corridor into the Queen of Hearts’ rose garden. Dandelion days! Sweet scattered spore of youth! When to the sessions of sweet silent thought we summon up. . and so on and so forth, jaw-jaw, bore-bloody-bore. No, the fact is that it’s pissing down and I’m a middle-class, middle-aged man making tea on a miniature gas stove in a tiny covert, while down the muddy track beside me ride upper-class middle-aged women on chestnut stallions exchanging the small change, the he-shagged-she-spat of hacking society.

Читать дальше