“What’s this going to run?”

“Tuition will be enrollment-dependent. We’re looking to offer top-dollar education at economy rates. That means special emphasis on each child’s distinctive needs, within a friendly, traditional, family-style setting. That’s the home school advantage.”

“Susy! Brad! Come in here!” Suddenly the two sopping pink children ran howling from pool to porch to kitchen; the screen door slammed and daughter and son stamped in, streaming water. They stopped and stood in the dirty puddles they made, before us.

Jenny leaned over to address them at eye level, “Susy, Brad, what are you supposed to do before you come in the house after swimming?”

“Um, dry?” This from Susy, assuredly the leader, by virtue of age and intelligence, of the sibling pair. She clasped her brother’s arm and began tugging him roughly back toward the screen door.

“Hang on,” called her mother.

Without letting go of Brad, Susy turned, her quick and forceful motion requiring Brad to race around her in a half-circle, like a cruelly led dance partner. He almost slipped and fell. Jenny scolded, “Brad, be careful, the floor’s wet. That’s why you’re supposed to towel off.”

Susy said, “I’ve got him, Mom. I won’t let him fall.” It was one of those beautiful family moments, the elder child’s urge to nurture and protect.

“Guys, this man wants to be your teacher. How do you feel about that?”

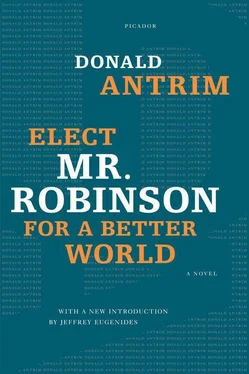

I couldn’t believe it. Was Jenny going to leave the education of her children, aged five and seven, in their own hands? The kids watched me with blank expressions. Susy seemed to be squeezing down on Brad’s arm — she was giving him an Indian burn. I smiled benignly, winked in a charming, avuncular, fun/conspiratorial way, generally nodded and grinned, as Jenny pressed her offspring, “What do you think? Want to study with Mr. Robinson?”

It was all about trust. I was being judged. By babes. It hadn’t occurred to me that I might have to win over the kids. But of course that’s always the way. Parents seem to embrace, almost unquestioningly, this bizarre, superstitious belief in infant clairvoyance, as though their “innocent” offspring have access to deep truths lost to them, to the parents — lost to maturity, cynicism, compromise. It’s one of our most esteemed cultural archetypes: the Prescient Child.

Brad and Susy didn’t strike me as a couple of oracles. In fact, they looked a little stupid. Even Susy looked stupid. Her mouth hung open, her hair stood up in wet spikes. I wanted to come to her defense, to hers and to Brad’s, to say to their mother, Don’t lay this on them, it has to be your choice, you’re their mother.

But then Susy spoke, in syllables soft and quiet, too quiet, almost, to be heard. “Okay.”

It was sweet, I could’ve hugged her. The home school was now officially in business. Enrollment, two.

“What will you call your school, Mr. Robinson?”

Good question. “We’ll see when we get farther along. A school is a place to make sober inquiry into the workings of the world and the mind. The name of the school, the right name, should reveal itself through this inquiry.”

Robinson Country Day? The Robinson Academy of Arts and Letters? The Robinson Institute? It was, after all, my idea, my ideology. It was my school, in my house.

I made a total of seven recruitment visits that day and the next, was successful at each, and in danger of dying only once, when Deborah and Carl Harris’s automatic garage door/catapult discharged a fusillade of calcified coral fragments, missing my head by inches.

Deborah Harris cooed apologies from the house, “Yoo-hoo, Pete, sorry about that. I told Carl to turn that thing off. He must’ve forgotten.”

“I’m fine,” rising from the Harrises’ lawn and brushing myself off. “That’s quite a device.”

“Hey, Pete.” It was Carl Harris, emerging from the dark garage with a crescent wrench in his hand. This man had once spent twenty days adrift on the high seas in a rubber raft, with no fresh water, surviving on the blood and flesh of fish caught bare-handed. LOST PLEASURE BOATER LIVES! ORDEAL CALLED “HARROWING,” ran the headline. Looking at Carl now, you wouldn’t guess such a thing possible. His skin was white, he had a gut; he ambled splayfooted on short, bowed-out legs. “Almost plugged you, Pete. I’ve been experimenting with a new garage-door-to-air gyroscope.”

We shook hands, and I said, not discourteously, “I guess it’s a good thing you’re still experimenting.”

“Hell, Pete. I had no idea you were out there. Please believe me. Please, accept my apologies.”

“Apologies accepted. It’s my fault, too. We’ve all got to be more careful these days.”

After that it was easy to get Deborah and Carl to commit their ten-year-old twin sons, Matt and Larry, to the school. I felt no remorse about playing on the Harrises’ contrition — they had almost killed me. Besides, the important thing was the education of the children. “Okay. School starts next Monday at eight. We haven’t worked out busing, so for now it’ll be the responsibility of parents to provide transportation to and from, and also you’ll need to supply Matt and Larry’s lunches. I recommend a sandwich, Pop-Tarts, and a piece of fruit. You might stock up on eight-ounce cartons of low-fat milk. Additionally, we ask all students to bring along a favorite toy. I typically kick off the year with an open play session, in order to implant the idea that learning is fun.”

Deborah said, “The boys’ favorite toys are their bow-and-arrow sets. Is that going to be all right in class?”

“What kind of arrows? Do they have metal points, or those rubber suction cups?”

“They’re carbon steel shafts with two-bladed broadheads and helical fletches. They’ll shave a hair,” said Carl.

“Tell you what. Have Matt and Larry bring their bows and quivers, and we’ll work out something in the way of a target range out back.”

Which is exactly what we did, come Sunday — we affixed, Meredith and I, to the tangerine tree out back, a round piece of cardboard painted eggshell-white and crayoned with an imperfectly round, lavender bull’s-eye. I held the flimsy target against the trunk and queried, “Higher? Lower?”

“Higher.”

“Here?”

“Up more.”

“Here?”

“ Higher. ” She came and held the target against the tree while I delicately tapped in narrow finishing brads meant for fiberboard or plaster, for hanging light pictures. I’d gotten the nails from the tool cabinet in the basement. They were short, soft, inadequate.

“Pete, can we talk? About those fifth- and sixth-grade bio electives I was going to teach? Seeing as, so far, there aren’t any fifth- or sixth-graders? I mean, there’s Susy Jordan, she’s smart enough for bio, she’s smart enough for physics I’ll bet, but you know, she’s only second grade. I thought I might take the opportunity to switch over from science, and do an elective in religion.”

“Religion?” It seemed like trouble, tackling religion at the elementary level, though what kind of trouble, and for whom, I wasn’t sure. Meanwhile the nails were bending; it was as if they were made of putty.

“Pete, I feel like I don’t know anymore what’s up and what’s down. It might help me to teach a course in spiritual doubt,” biting her lower lip, brushing away from her face, with one hand, a hovering green bug. Meredith’s abrupt movement shook free a couple of imperfectly pounded nails, which trembled from their ragged holes and dropped to the ground. No way this crummy cardboard bull’s-eye was going to withstand arrow impact. I chucked the remaining picture nails and Frisbeed the cardboard over the pit; it winged spinning in an upward arc, planing skyward, six, eight, ten feet. In higher air it paused — the illusion of rest at the peak of ascent — before plunging to rest atop a triangle of nautical spear tips.

Читать дальше