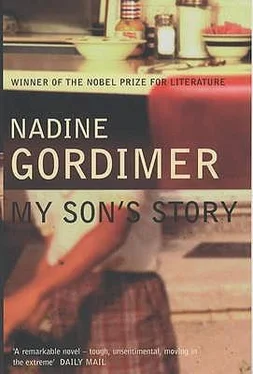

Nadine Gordimer - My Son's Story

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - My Son's Story» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, Издательство: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:My Son's Story

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Publishing PLC

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

My Son's Story: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «My Son's Story»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

My Son's Story — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «My Son's Story», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She was shut in there. She, who had held us close to her, not wanting our clothing to touch the walls of the prison corridors when she had taken us as children to see our father between his jailers on the other side of a dirty glass screen.

It was Hannah who found out where Aila was being held. Hannah's connections. It was Hannah who got a note from Aila's husband smuggled to her. Hannah had helped this family in trouble before. Many families. She had visited the father and husband in prison. The note was a minute tightly-rolled piece of paper — Sonny knew how such things had to be slipped in stuck to the bottom of a tin plate at meal time or under the inner sole of a shoe. Hannah did not read the note before she passed it on for delivery. A note came back in Aila's handwriting. The scrap of paper was the label soaked off an aspirin bottle. There were four words. Don't contact Baby. Wait.

Sonny did not tell his son about the notes in case he asked questions. Hannah was, after all, a comrade. Always had been, from the first; and as well. The cause was the lover, the lover the cause.

Hannah's concern about Aila was a comfort; and could not be. It seemed to him she lay beside him now as if in her professional capacity, as she had come to see him when he was in detention, one among others her persistence in devotion to the cause enabled her to get to visit, and to whom, as to him, she wrote morale-building letters. He did not go to her to talk. He could not talk to Hannah as he needed — about how he had let it happen, how Baby and that husband he had never seen had somehow recruited a woman like Aila, poor Aila of all people, exposed her to danger, used Aila — and all behind his back. He had let it happen, not seen it, not been told (he sometimes didn't believe the boy hadn't known, didn't know) because of this woman in his arms. She knew that and so it could not be talked about. It was something neither could have foreseen could ever happen, she with her romantic respect for his family, he with his confidence that his capacity for living fully, gained through her, never tapped in the shabby insignificance of a small-town ghetto across the veld, made him equal to everything his birth, country and temperament demanded— dedication to liberation, maintenance of family, private passion. She was the only chance. The source of ecstasy and hubris. She still was, when she made love to him. Aila was in prison, this woman was going away because the common good outside self required this. Yet when he sank into the warmth of her and himself, when the nerves of his tongue passed over the invisible down of her skin, the different, goose-fleshed texture of her buttocks, when her weight was on the pelt of his chest, blinded and choked they were flung together, curved round each other like mythical creatures fixed in a medallion of the zodiac.

A sign. — I'll be able to come back sometimes. — Oh thou weed.

Oh thou weed: who art so lovely faire, and smell'st so sweet that the sense aches at thee, Would thou had'st never been born.

They were going to see her. Father and son went with the lawyer to court to hear him argue application for bail. Sonny knew the procedure: Aila would be produced for formal charges to be laid, the case would be remanded for a later date. They would see her; she would materialize out of all the suppositions and talk and fears of the days since she disappeared — Aila in her new avatar. Disbelieving, Sonny, who himself had been the one to be produced from cells behind courts, did not know how to prepare for this apparition. Without being aware of it, he had dressed as he did when he was the one to be led into the dock.

The hearing was not at the great grey block of the city magistrate's courts in the district of the other great authority, the mining corporations' headquarters, where already an explosion of the kind that could be caused by the objects wrapped in curtain off-cuts had one day taken place. The court allotted was across the veld in Soweto. They travelled in the lawyer's air-conditioned car sealed like a diving bell from the mouthing noise and crowded faces in the combis that nosed past close and fast, and the huge shaking transport vehicles coming and going, crossing to industrial sites rearing up off the highway. In between, a green pile, the remnant of reed-beds, parted under gusts set up by traffic. The lawyer changed cassettes in his console dashboard and there was no conversation. Will sat on the back seat behind his father's head.

In the trampled veld where one area of Soweto ravelled into another the courts enclosed a quadrangle and their only access was from the verandah that ran along all four inner sides; red brick and shrubs, hangover from the old colonial style when the forts of conquest became the administrative oases, ruled into geometrical lawn and flowerbeds that demarcated the gracious standards of the invader from the crude existence of his victims. The lawyer left father and son at once, among people like themselves; drifting, standing, leaning against pillars, clustering around doorways from which they scattered to make way for the purposeful rumps of court officials. Waiting. All, like them, waiting to see a face that had been obliterated by uniforms, armoured vehicles and blind doors to break your fists on.

They were Sonny's constituents. He had taught their children, he had roused them to demand their rights, himself had disappeared into prison for them. But he never before had come, like them, to wait humbly for someone of his own flesh and blood caught up in some incomprehensible disaster. (Wasn't her flesh and blood mingled with his forever in the body of their son, trailing beside him.) These old women drawing snuff through their nostrils, mothers of murderers, these young women, painted and dressed to remind the car thief of the desires they provoked, these others, weary against the wall, swathed about with babies under blankets, and these hawking old men shrunk in baggy cast-off suits — it did not matter if they were waiting to see a common criminal or, like him, to have produced, habeas corpus, a prisoner of conscience (Aila! In that role!). He was one of them, now, in a way he had not known. Attending the trials of comrades was no preparation for this; there the solidarity of purpose made one's presence a defiance of the legal process. But to imagine the freedom songs and salutes for poor Aila!

The lawyer had gone to establish formalities and find out in which court she would appear. It was a long wait and at first the father and son walked again and again along the four sides of the verandah, as people do while expecting to be summoned any minute. — Why doesn't he come back? — His father spoke, the son knew, only to break the silence between them in their isolation among other people's voices; he didn't have to answer.

— At least tell us what the delay's about.—

— D'you want me to go and see if I can find him?—

— No point, Will.—

The son jumped down from the verandah. The shadow of one side of the building bisected the quadrangle into shade and sun and he stretched out on the grass among the people who followed warmth there. It was a kind of strange picnic, where patience substituted for holiday relaxation. Some people left the enclave and came back with fat-cakes and oranges, tins of Coke and fresh packets of cigarettes. Children played and fought furtively. Like them, he cupped his hand under a tap and drank. With the unconcern of routine, an employee in government-issue boots and overalls, singing a hymn in Sotho under his breath, unwound a hose and turned the flowerbeds into puddles.

Sonny stood above his son, made as if to prod him with the toe of his shoe. — Isn't it damp? (Smiling faintly.) Do you want something to eat?—

Neither wanted to be the one absent when the unimaginable moment came and she was brought into court. The father paused, with a gesture at the sun, went back to stand on the verandah. Perhaps he thought his son had dropped off, asleep; face up to the sky, eyes closed. But he was on his feet and leaping over the people on the grass before his father beckoned at the sight of the lawyer twisting his shoulders through the crowd on the verandah. — At last! — application's set for two this afternoon, though. The police agreed to bail but the Prosecutor insists on contesting… I know that fellow… big ego… it's absurd, but there you are. And by now no court's available this morning. I'll have to go to chambers and come back, there're urgent matters I have to attend to. But let's not waste time asking questions, just stick with me and say nothing. Will, take my bag. You're my clerk. Come.—

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «My Son's Story»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «My Son's Story» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «My Son's Story» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.