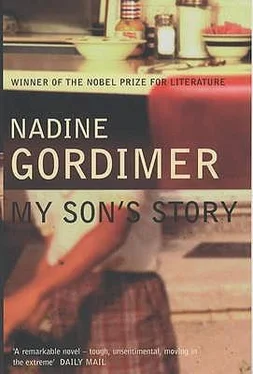

Nadine Gordimer - My Son's Story

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nadine Gordimer - My Son's Story» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2005, Издательство: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:My Son's Story

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Publishing PLC

- Жанр:

- Год:2005

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

My Son's Story: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «My Son's Story»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

My Son's Story — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «My Son's Story», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Since my mother's been away he's been spending time at home. He even brought out the chess board. We've played together a few evenings. But I'm careful. I don't know what he may be trying to get me into, now. I cook supper for us. Once I found the nerve to say something: —Haven't you got a meeting?—

He waited for a moment, showing me he knew, strictly between ourselves, my real question, and he replied to it. — No. No meeting. I'll be at home.—

At once I fetched my helmet and bike keys and put my head round the door. — Well, I'm off.—

He was playing that record he likes so much, some Mozart overture, he thinks he's only got to set up the scene and we'll do something educational together or watch soccer on the tele, dad and his boy. But he also knew I hadn't been going anywhere.

When I came home, late, the lights were still on. I thought he was waiting up for me and I went straight along the passage to my room. But there I became aware that there were voices, men's voices, in the house. They became more audible — their insistence, their cross-talk — as whoever it was must have left the sitting-room and been pausing in the entrance. There was the sound of the front door being closed and bolted by him, and the creaks and subdued clatter of his movements, tidying up, clicking off lights. He knocked at my door. After me again. I didn't say come in, I said, Yes?

He looked slowly round my room; I suppose it must be a year, more, since he's been in it. There was the beginning of a crinkling round his eyes, affirmation rather than recognition, at what I've kept, and he went over and stood a moment, head back, as if he were in an art gallery, not his son's bedroom, before a poster of a desert. That's new. Just space. I don't know what desert, where — I hoped he wasn't going to expect me to say.

He sat on the end of my bed and his weight tightened the covers over my feet, I felt pinned down. — There was a meeting, after all. Here.—

My father has such a wonderful smile, all the planes of his face are so strongly defined, so encouraging, the open feelings sculptured so deep — no wonder he is attractive to crowds, and to women. My mother and the other. I resemble him but my face is a mask moulded from his and I only look out through it, I don't inhabit it as he does. I suddenly was alarmed that he was going to talk about her, his woman, about the cinema, yes, at last, the whole story, that's what he'd come into my room for, Baby was right, you can't live with them, you ought to get away from them.

I had to speak quickly. — I heard someone leave. — I know. It's unfortunate. Something turned up soon after you'd left. I was settling down to read, for once. when did I last finish a book. I get halfway through and by the time I can get back to it I've forgotten the first part. D'you get any reading done, Will?—

Everything we say to each other has a meaning other than what comes out. That's what makes it difficult to be in the house with him. Now he was admitting he doesn't know anything much about me except that I know about the woman, who she is, where she lives. He has no hand in enriching my life (as he would think of it) anymore. Although we couldn't be members of the library when we lived across the veld, I mustn't forget he bought children's books and read to us.

I didn't tell him that in the past year I've read almost everything in his bookcase. If he'd been interested enough, if he'd come into my room for any reason other than his own concerns (what was it now, the danger of confession was averted but there must be something else) he might have found his Gramsci or his Kafka among the clutter on my table. I opened my hand towards Dornbusch and Fisher's Macroeconomics, on the reading list for my second-year courses.

— Well, that's essential. Of course I did it the other way round. you know, the other kind of books first. Poetry and stuff. I had a different idea of what's necessary. When I was your age. The wrong way round— He lifted his hands, seemed about to place one on the mound of my feet, touch me, but did not. — Ignorance.—

I was yawning uncontrollably, I didn't mean to be rude to him. I didn't know whether I was tense to get rid of him or I wanted him to stay.

— Will, you didn't hear anyone here tonight. You didn't hear anyone talking and you didn't hear anyone leave.—

After he'd said what he'd come for he continued to sit with me for — how long — a few moments, it seemed a long quiet time. Then he got up and went out softly, as if I were sleeping.

So that was it. Someone on the run, or an infiltrator from outside. Or there was a meeting with some of his people he doesn't want the rest to know about; since he's been home more, I've seen that he's in some kind of trouble with his crowd: these emotions don't have to be concealed in quite the same way as his love affair. There are long discussions with this one and that one — who come here openly, I don't have to pretend, for my own safety and his, I haven't seen them. There are reports in the newspapers speculating about changes and realignments in the organizations, including his, that make up the movement. That's his business; he doesn't need any complicity with me, beyond warning me to keep my eyes closed and my mouth shut. Which is already what he has taught me to do for other reasons. That's ended up being his only contribution to my further education.

Perhaps my mother said something to him about keeping an eye on me while she's away, and he feels he ought to do that much for her. So he's sacrificing the nights he could be spending in the big bed on the floor. As if I would ever know what time he crept in, midnight or dawn, I'm young and when I sleep, I sleep. Only older people wait up.

Home every night. Is it possible it's because he wants to be with me? It's for me?

Every third day, at the agreed hour, he waited alone in the room for a call from Lesotho, where she had gone because her grandfather had died. The cottage was locked up. She'd left him the key. Of course she was often alone in that room but he had never been there without her before. He tried to read but could not; the room distracted him, beckoning with this and that. He was a spectator of his own life there; the edge of the table he often bumped against when he went, dazed with after-love sleep, to the kitchen or bathroom; the shape of the word processor seen from a particular eye-level, now viewed from a different perspective; the huge painting with all its running colours that was more familiarly felt than seen, since when he stretched an arm behind his head, on the bed, he came in contact with the lumpy surface of what she had told him was the impasto. An ugly, meaningless painting, to him; there is always something about the beloved — some small habit — some expression of taste — one dislikes and about which one says nothing, or lies. Also she might have taken into account his background — lack of cultural context for the understanding of such work, so he had had to pretend (to protect each's idea of the other) that he thought it fine. Now he was alone with its great stain of incoherence spreading above the bed from which, at least, it had been out of sight. Of course, for her it was something handed down, like the old studio photograph of a bespectacled lady with cropped white hair — probably her grandmother — which stood in a small easel frame on top of the bookshelves. These things belonged to a life not followed, a continuity set aside; somehow he never thought of her in connection with a family. She wasn't placed, as he was, whatever he felt or did, with wife and son and daughter in the Saturday afternoon tea-parties.

Some days the call was delayed. She used a post-office booth for discretion, and they had agreed he should not call her at her grandfather's house, where others were likely to be around to overhear. He saw traverse the empty bed the stripe of sun that used to move like a clock's hand across their afternoons, over their bodies. Once he tidily took off his shoes and lay down on the bedcover's tiny mirrors and embroidered flowers. He must use the time to return to the problems of his relations with his comrades; this was the room, after all, the only room, where such matters could be examined openly; no fear of anyone taking advantage of frankness or admissions. But without her, Hannah, it was a stranger's room, a witness; while the house without Aila was unchanged, as if Aila were simply out of his way in some other part of it — maybe it was because the boy was still there, he and the boy among all Aila's family trappings.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «My Son's Story»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «My Son's Story» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «My Son's Story» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.