He went up from the dirty little street to the Hill of the Metropolitan Church. At a short distance the market, the bustle of traders. Then the corridor of Lipscani Street, once the fairy scene of dealers, now completely hushed, slumbering in languor and dirt. A few moments in front of the little church of Ionikie Stavropoleos. The graceful façade with its baroque verve, in contrast to the austere, limpid, geometric interior. He passed beside the palace, stopped before the Atheneum, and looked at the frieze on the arch, still glowing with forgotten crowned heads. On the left, a new construction — a massive white block. Shells from the earthquake three years before, filled with the concrete of the new foundations. Apathy, remembrance. The new model cages, their constricted functionalism. Two rooms kitchen and bath. Couple child refrigerator television. Reproduction of the same sordid honeycomb struggling to make ends meet … Mr. Dominic Vancea put himself at the mercy of idle meditation, alibi of whatever surprises were being prepared. “I feel as if I were preparing to commit a murder, or for the great love of my life, or for revelations that have kept being put off.”

The eccentric pedestrian advances without haste, slowly looking around him. A delicate spring morning: you become its unassuming condottière, torn from lethargy for a still obscure mission that Fate is producing for you beneath the sky’s huge pink hat. You become— finally finally! — the lever or puppet of the epic, bang bang bang, scooby-dooby-do.

And so Dominic Vancea, aged over below fifty, employed as multilingual receptionist at the Hotel Tranzit and at a persistent initiation into the delights of carnival, is sauntering with thin but even steps down Victory Boulevard. The pedestrian on this calm spring morning seems to have no definite purpose, not even when, for the umpteenth time, he carefully searches the back pocket of his white velvet trousers.

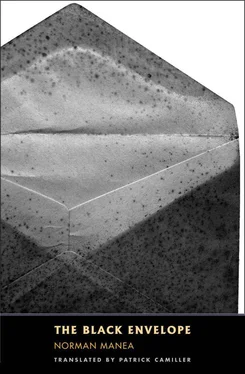

He stops for a moment: yes, the envelope is in his pocket, where he put it. He remains undecided, then begins to turn back. He appears to change direction. But after a few steps he abandons the abandonment. Yes, he has finally remembered the quotation that has been obsessing him for the whole walk: “Only what cannot be turned around and brought back to a prior state constitutes a true event.” That was indeed the quotation. He can’t recall the author’s name, but it doesn’t matter: the memory exercise is enough to satisfy him.

So, the morning is starting up again. No, it is continuing; that is, coming true. TOBACCONIST, DAIRY, TAILOR, Calea Rahovei, Metropolitan Hill, Lipscani Street, the Atheneum, Strada Bati  tei, Strada Vasile Lasc

tei, Strada Vasile Lasc  r: now the pedestrian is coming into Rosetti Square. At the crossing he again searches for the envelop in his trouser pocket. No, he won’t turn back: he seems determined to set a real event in motion.

r: now the pedestrian is coming into Rosetti Square. At the crossing he again searches for the envelop in his trouser pocket. No, he won’t turn back: he seems determined to set a real event in motion.

Before pushing the metal gate, he took a large white handkerchief from his pocket and wiped his perspiring face. As he removed the white silk, Dominic Vancea’s smooth firm face reappeared, now refreshed, from beneath the conjuror’s rectangle — a Roman consul’s head, as bald as if he had shaved it. Clear forehead, sharp eyes, straight, perfectly shaped nose, thin lips. He seemed to know the routine: enter quickly, self-importantly, with a distant air; don’t give any breathing space for someone to check your identity. Quite per-fect — the man on the door did not even have time to salute.

He went slowly up the narrow, twisting, dirty staircase and found himself in a dark corridor. Half of a bathroom, packed with stands and boxes, could be seen through a half-open door. It looked like a private lodging for several families. He entered a large open room, then passed a long table covered with red cloth to go into a similar room, smaller and rounder in shape. Four desks with some distance between them, and a typist’s worktable to the left of the door. Comrade Orest Popescu? the curly-haired blonde repeated in a simpering voice. Comrade Popescu is away at a briefing, and his deputy is in the organizing meeting. Meeting? Huh! What kind of meetings do they have? Surely we’re not at— But frank questions are not permitted. Vancea’s eyes stared, then he immediately pulled himself together, anxious not to appear taken aback.

The typist gestured toward the window without looking up from the keyboard. Yes, in fact there was a chair by the window. He sat on the chair, facing a solid, dark-haired man with a tie that was throttling him.

“You’ve come for the Year of the Disabled …”

“Well, I’d have liked to …”

“You must discuss it with the Executive first. I’m not allowed to give any kind of information. If she calls me in and says, Look, daddy — that’s what she calls me, daddy, or sometimes Iopo — discuss it with the comrade. If she tells me that, then of course—”

“I’ll wait, then: I’m not in any hurry. Will it go on for long?”

“Depends. It started just now. Maybe it won’t go on for long.”

“And you say it’s a meeting? What kind of a meeting can they be having?”

“Well, the Executive can speak normally. The president and the vice president, too — like us in fact, as you see. But that’s not to say, I mean, it makes no difference. We’re all united — we’re all one with the actual members.”

He looked like a foreman in a factory, tired, punished with having to wear a suit and tie and having to get involved in things that were too complicated and frightening for him.

“Maybe you’d like to read something. It passes the time, so you don’t get bored. Here are some of our publications. And our statutes. Maybe they will interest you.”

Tolea put the pile on his knees and took out the little brochure: statutes. “A public organization … which exists to train people for the political, economic, social, and cultural life of the country … for the work of construction … Socialism and Communism … its members are citizens … living within the country’s borders, deaf, deaf-mute, and hard-of-hearing, whose hearing loss is measured at more than 40 decibels … Also citizens who are able to hear and who support the Association may become members, in a proportion no higher than 10 percent.”

Dominic Vancea looked up at the office worker, who was keeping him under close scrutiny. They stared into each other’s eyes, as if communicating in some code or other. The visitor fidgeted on his chair in embarrassment. The office worker opposite him no longer appeared so weary — or so out of place in his role. For now the role suddenly struck him as unclear, as if those suspicious eyes, by scrutinizing the mimicry of reading, should have been able to guess at once whether the stranger did or did not deserve to be trusted by the sect.

“The numbers have increased,” he muttered, as if to himself, though still keeping a close watch. The intruder looked down at the statutes, but the guide continued to mumble.

“We have recorded a growth of more than 30 percent in the last five-year period. Forecasts for the next ten years show that we will achieve growth of—” A deep, soft, whispering voice — such was the activist’s way of speaking.

“The right to elect and be elected, to take part in discussions and to make proposals,” Dominic read in the brochure. The lines were beginning to dance in front of his eyes. “The Association is organized according to the principle of centralism. Leading bodies are elected from the bottom up; decisions are taken from the top down. The minority bows to the majority. Failure to comply—” He looked up and met the dark eyes trained on his bald head. Dark eyes, dark, bushy, knitted eyebrows. Dominic Vancea confronted the watching eyes. He tried without blinking to make out the scar by the dark-haired man’s left eyebrow. A faint mark, like a scratch, could be a sign or could be just a scratch — how was he to tell?

Читать дальше

tei, Strada Vasile Lasc

tei, Strada Vasile Lasc  r: now the pedestrian is coming into Rosetti Square. At the crossing he again searches for the envelop in his trouser pocket. No, he won’t turn back: he seems determined to set a real event in motion.

r: now the pedestrian is coming into Rosetti Square. At the crossing he again searches for the envelop in his trouser pocket. No, he won’t turn back: he seems determined to set a real event in motion.