“I'm not a martyr,” I said.

“You live in that town for what? I've read your memoir. You used to live out west; you used to go out and do things. It was so sad reading it, such a strong young man with courage and determination and slowly, gradually without you ever noticing it all went away.”

“I lost several things.”

“You didn't write what you lost.”

“The memoir ended right before I lost them. I will have to write another memoir to record what I lost.”

She handed me my eggs and veggies. She sat down next to me, smiled and said, “How many memoirs you going to write?”

“Simone De Beauvoir wrote four.”

“She was a professor of philosophy who had lived through Nazi occupation and the creator of modern feminism; you're a cook at a restaurant in Ohio.”

“I used to be a pizza boy.”

“Yeah, and Celine was like a doctor and fought in World War 1.”

“I haven't done anything.”

We finished breakfast and I went in the bedroom to check Gmail. Desmond Tondo was on and decided to G-chat with me:

Desmond: You're in New York.

Me: Yeah. I'm getting my picture taken.

Desmond: That sounds good. Where are you going to be tonight?

Me: At the Opium Christmas party.

Desmond: Good, I'm going to be there.

Me: I gotta take a shower but I'll see you tonight.

Desmond: Sounds good.

Desmond Tondo was a writer. He was also a very strange person. He graduated from Harvard with an English degree and then decided to work in the hiring department of a hedge fund company. He was an attractive Italian man. He wasn't Ellis Island Italian; his family came later in the sixties. He had one book published about a suburban landscape catching on fire and turning suburbia into flames. He had grown up in suburbia in Connecticut. He found suburbia hell on the human soul. His parents had fallen for the advertisement that raising kids in suburbia with good schools and a high level of security would make their child an adult that would be efficient in the modern workforce. It was true, he was efficient; he had succeeded. He made good money and he was living out his conception of the good life. Desmond had a very well-ordered life. He went to work in the morning. He wrote four days a week. He read a little every day and still had time to date women. He kept everything straight, clean, and organized. His face was shaved and he always smelled nice.

Last summer Desmond came to visit me for a few days. He didn't shave those days. He wore t-shirts with leather shoes. He came to write an article that appeared on the Huffington Post. Desmond and I drove around the Youngstown area for two days doing nothing. He was fascinated by the shittiness of it all. There were houses close together but it wasn't suburbs. It was summer and the poor blacks and whites were playing basketball on the streets. The crack heads were walking down the sidewalks. The old steel mills looked old and appalling. People were sitting on their porches drinking beer and swearing at each other. It was a very different scene.

At night we went to the local strip club where he would get dances from impoverished women that didn't even know what Harvard was. They assumed it was something only spoken of on television. He didn't have to play big shot. He didn't have to tell people what schools he went to, what hedge fund company he worked for, that he lived in Manhattan in a nice apartment. All those facts which are so crucial to life in New York City meant nothing in Youngstown. He seemed very much at peace in Youngstown. He was dressed normally and had a courteous personality. Everyone accepted him as a person just walking around the earth.

Desmond liked sex though: he liked women. When he was at the strip joint he spent a lot of money on the dancers. The last time I was in New York a pretty girl didn't pass us without him making a comment. He told me he would spend money to go on boats where everyone was having swinger sex. He had a real passion for sex, the way DiMaggio had for baseball or Brando had for acting. He put his heart and soul in the getting of sex, into the things women require for a man to have sex with them. And I assume even though I've never experienced personally, he must have devoted a lot of heart into the act of sex.

Petra and I were sitting on her bed saying nice things to each other. Things that people say to each other when they first meet and are having a very care-free good time. We were not serious. There was nothing serious about us. Soon I would be leaving. There was no reason for us to care about each other in any deep or meaningful way. We were nothing to each other. Two genitals that had showed up to fuck each other. Our relationship was like a roller coaster. We got on, we rode. We had fun; we got off. We were never going to be in-love. We were never going to get married and have children. I was never going to learn the most embarrassing moments of her childhood. She was never going to learn what hospital I was born in. We were never going to meet each other's parents. We would never drive across country together or visit Rome, standing together looking upon The Coliseum. We would never sit at a Waffle House, her eating a breakfast burrito, me a waffle and grits talking about the day's activities. Petra was from the south, but her Waffle House and grits days were over. She ate a lot of seaweed and rice. If she came to Youngstown, she would view the people that surrounded me as sociological animals one looked down upon; I viewed them as sociological animals too. But they were my friends and enemies. An educated white collar person couldn't hate poor people, for they were screwed and disenfranchised and that's why they acted like that. They could do that because they didn't have to be around them. They could leave and go back to their suburban neighborhood and white-collar job. I couldn't afford those feelings. I was surrounded by them, I worked with them; I was one of them. My private life was that of literature and philosophy. In the privacy of my own home I would read and write things. But my public life was that of a stumblebum working at cheap labor jobs swearing and not shaving every morning like everyone else.

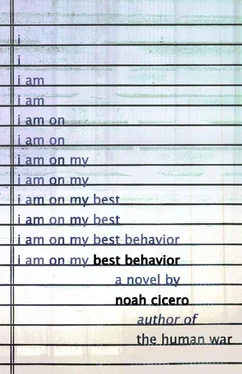

When I got my first book published six years ago before sitting with Petra people thought I would eventually pick up and go to New York City and try to become a writer. I had thought that myself. I had traveled out west; I had lived in several different states before the age of 23, states as far away from Ohio as Oregon and California. New York City was only six hours away from Youngstown. When looking back on it, perhaps I should have left to New York City. I would have been surrounded by writers. I would have been doing readings and making connections. It was logical if I wanted to become a writer. I was scared though: scared of not being smart enough, of not being good enough. I was just a little boy from Ohio; I wasn't a rich kid who had been to an Ivy League college. I was no one. I was a butcher's son, a factory worker's son. I was a child of the Rust Belt. Came from blue collar lands. I was so full of dreams when I was young, I was going to go to New York City and shock everyone. I was going to make them believe that blue collar people could think and write. I didn't though. I never had the courage. I didn't go to college for years. Instead of preparing to get that intelligent and aware of my world, I sat in in my house and read Wittgenstein alone.

When people in New York City or online would tell me what good college they went to or what their parents did. I felt little. I felt out of place. It was not my world. I felt like I didn't have a right to be there talking to them. I didn't belong. It was not my world, it was theirs. I was merely a guest. In Ohio I felt like a person, a participant in events. I was of Youngstown, I could say with pride, “My mother worked for GM.” I could say my name was Baradat, and I was related to the people who owned Baradat's Market and they would say they used to shop there and they loved their pigs in the blanket. I had a link to the land. I was anchored; I was a citizen in Youngstown. In New York City I was a subject. I received privileges from the white collar literary world, not rights.

Читать дальше