PRAISE FOR NORMAN RUSH’S MATING

“The best rendering of erotic politics … since D. H. Lawrence … a marvelous novel, one in which a resolutely independent voice claims new imaginative territory … The voice of Rush’s narrator is immediate, instructive and endearing.”

— The New York Review of Books

“Witty, raunchy … prodigiously aspiring … a remarkable book … His protagonist is a memorable female character: a continually shifting prism that revolves from dashing to needy, from witty to morose … wonderfully varied and pungent.”

— Los Angeles Times Book Review

“It draws the reader steadily in. Not toward the heart of darkness but toward brilliant illumination.”

— The New York Times

“Bold and ambitious … delightful, provocative.”

— San Francisco Chronicle

“Brilliantly written … utterly sui generis !.. Rush has alerted us to the transfiguring power of passion.… He deploys the narrative voice with … brio … wit and persuasiveness.”

— Mirabella

“A novel that doesn’t insult the intelligence of either its readers or its characters: a dryly comic love story about grown-up people who take the life of the mind seriously and know they sometimes sound silly … Mating is state-of-the-art artifice.”

— Newsweek

“An audaciously clever novel with substance as well as flash.”

— Detroit Free Press

Everything I write is for Elsa, but especially this book, since in it her heart, sensibility, and intellect are so signally — if perforce esoterically — celebrated and exploited. My debt to her, in art and in life, grows however much I put against it. I also dedicate Mating to my beloved son and daughter-in-law, Jason and Monica, to my mother, and to the memory of my father, and to my lost child, Liza.

Another Disappointee

In Africa, you want more, I think.

In Africa, you want more, I think.

People get avid. This takes different forms in different people, but it shows up in some form in everybody who stays there any length of time. It can be sudden. I include myself.

Obviously I mean whites in Africa and not black Africans. The average black African has the opposite problem: he or she doesn’t want enough. A whole profession called Rural Animation exists devoted to making villagers want more and work harder to get it. Africans are pretty ungreedy — elites excepted, naturally. Elites are elites.

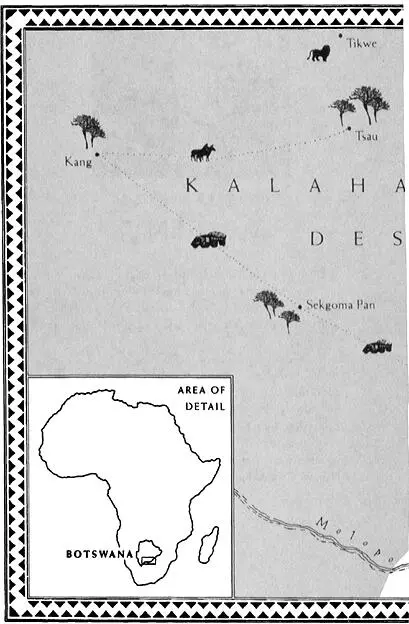

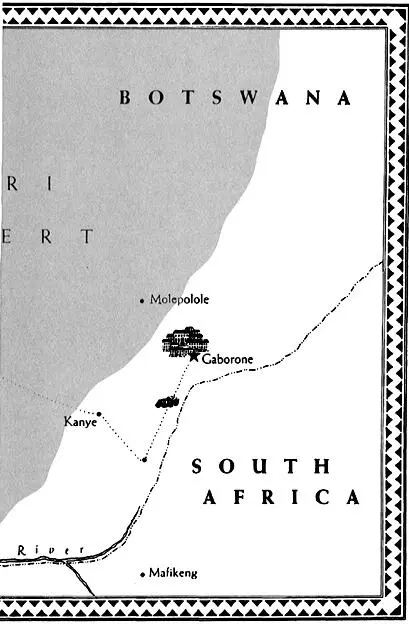

But in Africa you see middleclass white people you know for a fact are highly normal turn overnight into chainsmokers or heavy drinkers or gourmets. Suddenly you find otherwise serious people wedged in among the maids of the truly rich in the throng at the Chinese butchery, their faces clenched, determined to come away with one of the nine or ten half pints of crème fraîche that arrive from Mafikeng on Wednesdays at three. You see people fixate on eating wonderfully despite the derisory palette Botswana offers. Or they may get into quantity sex. Or you can see it strike them there’s no reason they shouldn’t take a stab at getting rich before they have to leave Africa. Most expatriates only stay for a few years. And like clockwork when they get toward the end they start buying up karosses or carvings to resell, or they decide to buy real estate through Batswana proxies or in one case to found the first peewee golf course south of the Sahara. I knew someone who was an echt mama’s boy in real life who took insane risks smuggling wristwatches into Zimbabwe on weekends. He was at the very end of his contract. He was teaching law at the University of Botswana.

In my case, disappointment was behind it. I got disgusting. I was typical — avid, and frantic. It was fall 1980, meaning spring in Africa. Africa had disappointed me. I had just spent eighteen months in the bush, all by myself basically. My thesis was in nutritional anthropology, and what I had been supposed to show was that fertility in what are called remote-dwelling populations fluctuates according to the season, because a large part of what remote dwellers eat depends on what they can find when they go out gathering, which should affect fertility. Or so I had been led to believe. It was unso. I had to hunt for gatherers. Gathering was a dead issue in my part of the bush. Normal-type food seems to have percolated everywhere, even into the heart of the Tswapong Hills. One way or another, people were getting regular canned food and cornflakes, or getting relief food, sorghum and maize, from the World Food Program. So nobody bothered with gathering much, and I had an exploded thesis on my hands.

On top of which I had been a bystander during something interpersonally very nasty in Keteng, the main village in my research zone. A Dutch cooperant had been hounded to death by the local power structure — old Boer settler families who’d become Botswana citizens when independence came. It still bothers me. Then on top of that I was having irregular periods, which turned out to be due to physical stress and my monochrome diet, which was as I suspected but which I needed to do something about, not be worried about. It intersected my turning thirty-two. I gave up and retreated to the capital, Gaborone, ostensibly to regroup but in fact to regress.

When I find myself in a homogeneous phase of my life, I like to have a caption for it. Guilty Repose is what I came up with for my caesura in Gaborone, which softens it: I went slightly decadent. It only lasted a couple of months.

I had no real excuse for not going back to the U.S. I told myself it was the prospect of another birthday at the hands of my mother. The more birthdays with her I missed, the more grandiose and excruciating the catch-up birthday always was, and I was years overdue. I had de facto promised to spend my thirty-second with her if I was back in the States. I knew it was her guilt — over being poor when she raised me, over being gigantic — that drove her to be so Wagnerian about my birthdays, but that wasn’t enough. I was enervated.

Wanting company entered into it. I was tired of my own company and there was no one I had left behind or even on the horizon in the States. I was feeling sexually alert. There’s no place like Gaborone for a detached white woman with a few social graces, even someone feeling very one-down. In fact for a disappointee Gaborone was perfect, because you circulate in a medium of other whites who are disappointed too. Nobody uses the word.

Accumulated Whites

There are more whites in Africa than you might expect, and more in Botswana than most places in Africa. Whites accumulate in Botswana. Parliament works and the courts are decent, so the West is hot to help with development projects: so white experts pile in. Botswana has almost the last hunter-gatherers anywhere, so you have anthropologists and anthropologists manque like me underfoot. From South Africa you get fugitive white and black politicals, the whites mostly passing through, except for the bravest and hardiest. The Boers can reach out and touch anyone they want in Gaborone. Spies of all kinds are profuse, since everybody wants to know when the Republic of South Africa is going to combust and Gaborone is only five hours by road from Pretoria and Johannesburg. The Russian embassy is huge. And then Botswana is a geographical receptacle for civil service Brits excessed as decolonization moved ever southward. These are people who are forever structurally maladapted to living in England. This is their last perch in Africa. Tories from the Black Lagoon, or Paleo-Tories, Nelson Denoon called them, their politics are so primitive-right. They’re interesting from the anthropological standpoint, but there are too many of them. Then you have white cooperants and volunteers, a hundred in the Peace Corps alone. You have droves of white game hunters and viewers heading north. Botswana has the last places in Africa wild animals have never seen a white face. There are only a million Batswana. And there are the missionaries.

Читать дальше

In Africa, you want more, I think.

In Africa, you want more, I think.