22Sorge: “In the summer of 1914, I visited Sweden on vacation, and returned to Germany by the last boat available. The Austrian Archduke had been assassinated in Sarajevo, and World War I broke out. I volunteered for service immediately, joining the army without reporting to my school or taking the final graduation examination.” This period may be described as “from the schoolhouse to the slaughterhouse.” Sorge was sent to the Eastern Front (Galicia). He was befriended by an old stonesman from Hamburg, a real leftist, whose head was shattered to smithereens before Sorge’s very eyes, a piece of skull bone cutting his face (a permanent scar remained). In July 1915, Sorge was wounded by shrapnel in his right leg. In 1916, a bullet struck him from the back, taking out his bowels. Sorge was transported to a field hospital, conscious, watching with listless amazement his viscera throbbing in his hands. Exhausted surgeons gave him no hope of survival, but patched him up and let him occupy a bed. Sorge’s next-bed neighbor, a Jewish boy, crushed his skull against the bed frame, as Sorge was helplessly writhing in his own pain. In early 1917, fully and miraculously recovered, Sorge was sent back to the Galician front, where he became one of the best sharpshooters in his division, specializing in eliminating enemy snipers.

23Sorge was a passionate chess player. He played against Kurt Gerlach (Sorge: 25—Gerlach: 50); Pyatnitski, Kuusinen, Klopstock (Sorge: 12—Pyatnitski, Kuusinen, Klopstock: 12); Berzin (Sorge: 131—Berzin: 127); Klausen (Sorge: 1—Klausen: 0); Ozaki (Sorge: 50—Ozaki: 49); Hanako (Sorge: 111—Hanako: 0); Ott (Sorge: 45—Ott: 12); and he played against himself daily.

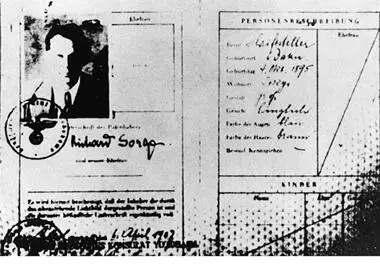

24Sorge: “Legitimate and plausible cover is absolutely essential for a spy. I worked as a news reporter and found that the foreign correspondent is conveniently situated for the acquisition of information of various types, but that he’s closely observed by the police. I believe, however, that the best thing an agent can do is render himself an intellectual: a professor, a writer, a scholar. Generally speaking, the intellectual class is made up of men of average or less than average intelligence, and the agent who assumes such a cover would be quite safe from detection by police. Moreover, as an intellectual with extensive scholarly connections (which he would utilize as sources or transmitters of information) he could associate with people who possess information they know nothing about, he could ask ostensibly ludicrous questions and develop trust. I think that intellectuals are the pets of the world, digging holes in the backyards of history. They can move around without arousing suspicion.”

25In the files of the Frankfurt-Police, dating from 1927, there is a vague and unconfirmed report showing that a Dr. Richard Sorge left for the United States on January 24, 1926, and spent some time in California, working in Hollywood film studios. The only admission, however, made by Sorge of visiting America was on his way to Japan. Herr Alexander Hemon, a researcher at the German Foreign Office Archives, claims that there is a possibility that Dr. Richard Sorge, identified by the police as being in Frankfurt in 1925 and 1926, was “not the Soviet spy who was working in Tokyo and on mysterious missions abroad, but someone else, of whom we know nothing.”

26On the evening of Tuesday, October 7th, 1941, Sorge had arranged a customary meeting with Ozaki at the Asia Restaurant, in the South Manchurian Railway building. He kept the appointment in vain, devouring sake, absentmindedly flirting with a woman (“a Mary Kinzie lookalike”), gorging on escargot at the next table. Miyagi was due to come to Sorge’s house two days later, but failed to appear. On Friday, October 10th, Klausen and Voukelitch called on Sorge, by a prior arrangement, in an atmosphere of mounting disquiet. Voukelitch telephoned Ozaki’s office and received no answer. Klausen: “The air was heavy, and Sorge said gravely — as if our fate was sealed—‘Neither Joe nor Otto showed up to meet us. They must have been arrested by the police.’”

After Voukelitch and Klausen left Sorge’s house and strayed toward their respective fates (Voukelitch: died of typhus in the prison hospital; Klausen: scorched in his prison cell by an American bomb during an air raid), Sorge could not rest and instead made frantic love to Hanako, who was gentler and smoother than ever. At two o’clock after midnight, a plainclothesman (name lost), with two uniformed, sleepy policemen, knocked politely on Sorge’s door and, receiving no answer (Sorge and Hanako approaching another climax), shouted: “We have come to see you about your recent traffic accident.” Sorge appeared at the door in pajamas and slippers and then was, without further exchange, bundled into an inconspicuously black police car, protesting (in whisper, so as not to wake his neighbors) that his arrest was illegal.

27The procurator directly responsible for the interrogation of Sorge was Yoshikawa Mitsusada of the Thought Department of the Tokyo District Court Procurator Bureau. Yoshikawa had an extensive knowledge of current political and economic thought, including Marxism. It was rumored that he had been a Marxist himself when he was a student at Tokyo Imperial University. Soon after graduating from the university, he had written a comprehensive study of the geisha wage system. It seems that there was some mutual admiration between the two of them. Yoshikawa: “In my whole life, I have never seen anyone as great as he was.” After the sentence, at their last meeting, Sorge asked Yoshikawa to be kind to Hanako-san: “She will marry a professor in the end and have a boring and happy life. Don’t do anything to her.”

28Some of Sorge’s information, seemingly petty, was passed on by way of the Fourth Bureau to the GPU, which used it to build the foundations for what would become the KGB’s Sixth Division of the First Directorate — the infamous Index. The Index was a vast collection of biographical and personal data about everyone who might, even very remotely, be of use at some time or another, to Soviet espionage. The Index files contained information about sexual preferences (obtained by voyeuristic monitoring or tempting agents); eating (restaurant bills, etc.), and sleeping (calls in the middle of the night, monitoring, etc.) habits; about sports teams affiliations; about reading interests (subscription lists, library records, etc.) and, often, recorded stories, apparently unrelated, which helped the one in charge of the particular individual to assess what sort of person he or she was to utilize. The information could be used for blackmail, or for assuming the right approach when recruiting, or for plugging damaging information into the public’s mind. Cold War defectors brought numerous stories about the Index and, almost without exception, claimed that the official slogan was “We know everything!” In pre-computer times, only the Nazi Gestapo had much the same kind of organization, but it was not nearly as detailed nor all embracing as the Index. There are claims, dating all the way from the sixties, that the United States Government agencies (CIA, FBI, or both) are building a computer database, based on the principles similar to the Index’s, but none of those claims has ever been confirmed.

Читать дальше