"I don't know. What would you want to do?"

She seemed lifetimes away. She wasn't talking to me. She listened to some invisible messenger. "I don't know what I want. I don't know what to hope for. Part of me wants it all to be taken out of our hands. Maybe we think too much, Beau. Maybe we've always thought too much."

I thought a baby now, with things so volatile, would be disaster. She felt my failure of will, and to her, it was already a murder.

"What do you want?" she dared me. "What do you think?"

To be born is as painful as to die. "I think we need to wait and see what we are talking about."

We waited. We waited seven weeks. In hope or fear, C. missed a period. She threw up continually. She wasted and turned the color of a sunken copper statue. Then one morning, we got an All Clear that left her suicidal with relief.

Not long after, she announced at dinner the end of the narrative.

My life with C. was a long training. I learned most of my adult truths with her. I learned how to travel light, how to read aloud. I learned to pay attention to the incomprehensible. I learned that no one ever knows another.

I learned her condition of statelessness, steeped in survivor's guilt. I learned how to make a virtue of necessity. How to assume a courage when I had it not. I mimicked that skill she exercised without thinking, for which I loved her most of all. I learned from her how to keep fitting myself against those things that left me for dead.

I learned that only care has a prayer of redressing the unlivable terms of politics. Yet I learned that a love fostered on caretaking crippled the loved one, or, one day — worse — it did what it promised and worked its worldly cure.

"How would you like," I asked A., "to participate in a noble experiment?"

I winced to hear myself talk to the woman. I still took a 50 percent hit in intelligence each time I saw her. Actual attempts at conversation halved that half. Sentences of more than five words I had to rehearse well in advance. I hoped A. might have a fondness for the pathetic. That idiocy lent me comic appeal.

I had lived by the word; now I was dying by the phoneme. The few good cadences I managed to complete competed with countless other claims on A.'s attention. We could not speak anywhere for more than three minutes without someone greeting her effusively. This self-possessed child, who I'd imagined spent solitary nights reading Auden and listening to Palestrina, was in fact a sociopath of affability.

The bar where we sat overflowed with her lost intimates. "Experiment? Just a sec. I'm getting another beer. You want something else?"

She curved her fingers back and touched them to my shoulders. I was finished, done for, and had no objections.

I watched A. take our glasses up to the bar. Within a minute, she, the bartender, and a knot of innocent bystanders doubled over with laughter. I watched the bartender refill the beers and refuse her proffered cash. A. returned to our booth, still grinning.

"Do you play pinball?" she asked. "They have this fantastic machine here. I love it. Come on."

She bobbed into the crowd, not once looking back to see if I followed.

My pinball was even more pathetic than my attempts at conversation. "How do you get this gate to open? What happens if you go down this chute?"

"I haven't the faintest idea," A. answered. "I just kind of whack at it, you know? The lights. The bells and whistles." Volition was moot musing. The little silver ball did whatever it wanted.

Everything I thought A. to be she disabused. Yet reality exceeded my best projections. A. engaged and detached at will, immune to politics. She sunned herself in existence, as if it were easier to apologize than to ask for permission.

That spring body — its fearless insouciance, the genetic spark, desire's distillation of health — made anyone who looked on her defer to the suggestion of a vast secret. And when she looked back, it was always with a bemused glance, demure in her pleasure, reining up in decorous confusion that nobody else had put things together before now, had gleaned what was happening. Every living soul had gotten lost, forgotten its power, grown old. She alone had broken through, whole, omnipotent with first growth, her ease insisting, Remember? It's simple. And possessing this, A.'s mind became that idea, however temporarily, forever, just as the meter of thought is itself a standing wave, an always, in its eternal, reentrant feedback.

In A.'s company, everyone was my intimate and beer and peanuts all the nutrition I needed. Prison, with her, would be a lime-tree bower. In those scattered minutes that she let me trot alongside her, I could refract first aid from the air and prosody from stones. I could get by without music, without books, without memory. I could get by on nothing but being. If I could just watch her, I imagined, just study how she did it, I might learn how to live.

I kind of whacked at the pinhall. A. laughed at me. I amused her — some kind of extraterrestrial. "That's it. Squeeze first. Ask later."

"But there has to be some kind of system, don't you think?"

"Oh, probably," she sighed. She took over from me when I drained. She tapped into the bells and whistles, entranced. "So what's this noble experiment?"

I had fifteen seconds between flipper twitches to tell her about Helen.

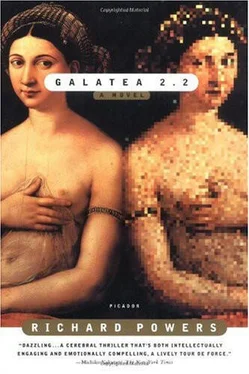

"Well, it's like this. We're teaching a device how to read."

"You what?" She stopped flipping and looked at me. Her eyes swelled, incredulous, big as birthday cakes. "You're joking. You're joking, right?"

I took A. to the Center. Two whole hours: the longest I'd ever been in her presence. That day doubled the total time I'd spent with her up until then. I blessed Helen for existing. And shamed myself at the blessing.

A. watched as I stepped through a training demo. Helen enchanted her. She could not get enough. "It can't be. It's not possible. There's a little homunculus inside, isn't there?"

"Not that I know of."

Delight grew anxious. A. wanted to speak to the artifact herself, without mediation. She asked for the mike. I could not refuse her anything.

"Who's your favorite writer, Helen? Helen? Come on, girl. Talk to me."

But A.'s voice, on first exposure, disquieted Helen as much as it had me. The nets clammed up as tight as a five-year-old remembering the parent-drilled litany, Stranger, danger.

"Pretty please?" A. begged. "Be my friend?" She wasn't used to rejection.

"Let's talk about 'The Windhover,' " I suggested to Helen.

"Good. I want to," Helen said.

A. clapped her hand to her mouth. Her eyes would have wetted, her heart broken with ephemeral pleasure, had they known how.

"What do you think of the poem?"

"I understand the 'blue-bleak embers,' " Helen claimed, failing to answer the question. "But why does he say, 'Ah my dear?' Who is 'my dear?' Who is he talking to?"

I'd read the poem for Taylor, at an age when A. would have been considered jail bait. I'd memorized it, recited it for anyone who would listen. I'd analyzed it in writing. I'd pinched it for my own pale imitations.

"I don't know," I confessed to Helen. "I never knew."

I glanced over at A. for advice. She looked stricken. Blue-bleak. "What on earth are you teaching her?"

"It's Hopkins," I said, shocked at her shock. "You don't…?"

"I know what it is. Why are you wasting time with it?"

"What do you mean? It's a great poem. A cornerstone."

"Listen to you. Cornerstone. You didn't tell me you were Euro-retro."

"I didn't know I was." I sounded ridiculous. Hurt, and worse, in hating how I sounded and trying to disguise it.

"Has she read the language poets? Acker? Anything remotely working-class? Can she rap? Does she know the Violent Femmes?"

Читать дальше