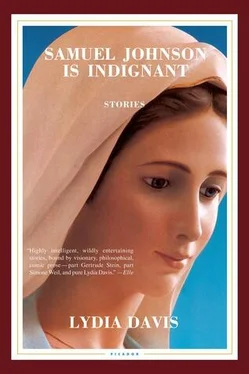

Lydia Davis - Samuel Johnson Is Indignant

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Lydia Davis - Samuel Johnson Is Indignant» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2001, Издательство: Picador, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Samuel Johnson Is Indignant

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador

- Жанр:

- Год:2001

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Samuel Johnson Is Indignant: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Samuel Johnson Is Indignant»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Samuel Johnson Is Indignant — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Samuel Johnson Is Indignant», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She shakes hands with a great many people until someone breaks her wrist.

That evening, Missy knows definitively who Marie really is. And reciprocally.

Fabulous razzia: Marie has pocketed in addition fifty thousand dollars advance for her autobiography, though the book is to be insipid. Missy has at every point kept her promises, and well beyond.

The crystalline lenses of the beautiful ash-gray eyes are becoming each day more opaque. She is convinced she will soon be blind. Marie and Missy embrace each other crying.

Let us say right away, however, that these two slender dying creatures will nevertheless meet again. It will be seven years later, again at the White House…

Missy and Marie certainly belong to the same race. That of the irreducibles.

And now the red curls of Perrin, discoverer of Brownian motion, have become white.

These conferences to which she travels often weigh on her. She finds only one pleasure in them: still a devotee of excursions, she vanishes and goes off to discover a few of the splendors of the Earth. For over fifty years a recluse, she saw almost nothing.

From everywhere, she writes and describes to her daughters. The Southern Cross is “a very beautiful constellation.” The Escurial is “very impressive”…The Arab palaces of Grenada are “very lovely”…The Danube is bordered with hills. But the Vistula…Ah! The Vistula! With its most adorable banks of sand, etc. etc.

One afternoon in May 1934, at the laboratory where she has tried to come and work, Marie murmurs: “I have a fever, I’m going home…”

She walks around the garden, examines a rosebush which she herself has planted and which does not look well, asks that it be taken care of immediately…She will not return.

What is wrong with her? Apparently nothing. Yet she has no strength, she is feverish. She is transported to a clinic, then to a sanatorium in the mountains. The fever does not subside. Her lungs are intact. But her temperature rises. She has attained that moment of grace where even Marie Curie no longer wants to see the truth. And the truth is that she is dying.

She will have a last smile of joy when, consulting for the last time the thermometer she is holding in her little hand, she observes that her temperature has suddenly dropped. But she no longer has the strength to make a note of it, she from whom a number has never escaped being written down. This drop in temperature is the one that announces the end.

And when the doctor comes to give her a shot:

“I don’t want it. I want to be left in peace.”

It will require another sixteen hours for the heart to cease beating, of this woman who does not want, no, does not want to die. She is sixty-six years old.

Marie Curie-Sklodowska has ended her course.

On her coffin when it has descended into the grave, Bronia and their brother Jozef throw a handful of earth. Earth of Poland.

Thus ends the story of an honorable woman.

Marie, we salute you…

She was of those who work one single furrow.

Nevertheless, the quasi-totality of physicists and mathematicians will refuse fiercely and for a long time to open what Lamprin will call “a new window on eternity.”

Mir the Hessian

Mir the Hessian regretted killing his dog, he wept even as he forced its head from its body, yet what had he to eat but the dog? Freezing in the hills, far away from everyone.

Mir the Hessian cursed as he knelt on the rocky ground, cursed his bad luck, cursed his company for being dead, cursed his country for being at war, cursed his countrymen for fighting, and cursed God for allowing it all to happen. Then he started to pray: it was the only thing left to do. Alone, in midwinter.

Mir the Hessian lay curled up among the rocks, his hands between his legs, his chin on his breast, beyond hunger, beyond fear. Abandoned by God.

The wolves had scattered the bones of Mir the Hessian, carried his skull to the edge of the water, left a tarsus on the hill, dragged a femur into the den. After the wolves came the crows, and after the crows the scarab beetles. And after the beetles, another soldier, alone in the hills, far away from everyone. For the war was not yet over.

My Neighbors in a Foreign Place

Directly across the courtyard from me lives a middle-aged woman, the ringleader of the building. Sometimes she and I open our windows simultaneously and look at each other for an instant in shocked surprise. When this happens, one of us looks up at the sky, as though to see what the weather is going to be, while the other looks down at the courtyard, as though watching for late visitors. Each is really trying to avoid the glance of the other. Then we move back from the windows to wait for a better moment.

Sometimes, however, neither of us is willing to retreat; we lower our eyes and for minutes on end remain standing there, almost close enough to hear each other breathing. I prune the plants in my windowbox as though I were alone in the world and she, with the same air of preoccupation, pinches the tomatoes that sit in a row on her window sill and untangles a sprig of parsley from the bunch that stands yellowing in a jar of water. We are both so quiet that the scratching and fluttering of the pigeons in the eaves above seems very loud. Our hands tremble, and that is the only sign that we are aware of each other.

I know that my neighbor leads an utterly blameless life. She is orderly, consistent, and regular in her habits. Nothing she does would set her apart from any other woman in the building. I have observed her and I know this is true.

She rises early, for example, and airs her bedroom; then, through the half-open shutters, I see what looks like a large white bird diving and soaring in the darkness of her room, and I know it is the quilt that she is throwing over her bed; late in the morning her strong, pale forearm flashes out of the living room window several times and gives a shake to a clean dustrag; in housedress and apron she takes vegetables from her window sill at noon, and soon after I smell a meal being cooked; at two o’clock she pins a dishcloth to the short line outside her kitchen window; and at dusk she closes all the shutters. Every second Sunday she has visitors during the afternoon. This much I know, and the rest is not hard to imagine.

I myself am not at all like her or like anyone else in the building, even though I make persistent efforts to follow their pattern and gain respect. My windows are not clean, and a lacy border of soot has gathered on my window sill; I finish my washing late in the morning and hang it out just before a midday rainstorm breaks, when my neighbor’s wash has long since been folded and put away; at nightfall, when I hear the clattering and banging of the shutters on all sides, I cannot bear to close my own, even though I think I should, and instead leave them open to catch the last of the daylight; I disturb the man and woman below me because I walk without pause over my creaking floorboards at midnight, when everyone else is asleep, and I do not carry my pail of garbage down to the courtyard until late at night, when the cans are full: then I look up and see the house-fronts shuttered and bolted as if against an invasion, and only a few lights burning in the houses next door.

I am very much afraid that by now the woman opposite has observed all these things about me, has formed a notion of me that is not at all favorable, and is about to take action with her many friends in the building. Already I have seen them gather in the hallway and have heard their vehement whispers echoing through the stairwell, where they stop every morning on their way in from shopping to lean on the banisters and rest. Already they glance at me with open dislike and suspicion in their eyes, and any day now they will circulate a petition against me, as my neighbors have done in every building I have ever lived in. Then, I will once again have to look for another place to live, and take something worse than what I now have and in a poorer neighborhood, just so as to leave as quickly as possible. I will have to inform the landlord, who will pretend to know nothing about the activity of my neighbors, but who must know what goes on in his buildings, must have received and read the petition. I will have to pack my belongings into boxes once again and hire a van for the day of departure. And as I carry box after box down to the waiting van, as I struggle to open each of the many doors between this apartment and the street, taking care not to scratch the woodwork or break the glass panes, my neighbors will appear one by one to see me off, as they always have. They smile and hold the doors for me. They offer to carry my boxes and show a genuinely kind interest in me, as though all along, given the slightest excuse, they would have liked to be my friends. But at this point, things have gone too far and I cannot turn back, though I would like to. My neighbors would not understand why I had done it, and the wall of hatred would rise between us again.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Samuel Johnson Is Indignant»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Samuel Johnson Is Indignant» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Samuel Johnson Is Indignant» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.