‘I always did the best I could.’

She drops the mirror on her lap. She gives up on the brushing, her wrist limp. She looks right at me.

‘Maybe the people reading the book will believe you, but you can’t believe yourself. You know. You can still see Granny’s face when you threw her to the floor, after squeezing her arm or striking her in the face with your hand. You can still remember all the times they looked at you with disappointment, with pity. You’re afraid that they’ll take away from you something that was never yours, but which for a moment you believe belongs to you just because you’re you. You’ve disappointed yourself, you feel pity for yourself, and for a moment you believe that other people should be the ones to pay for everything you did wrong and for everything you couldn’t do.’

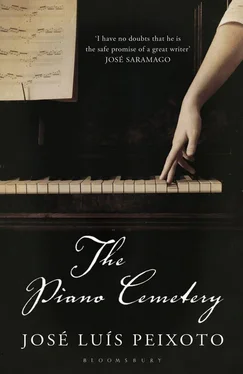

She looks at me. Silence. She gets up, still looking at me. Her footsteps on the dust. She skirts around pianos, parts, piles of keys, makes her way down passageways and leaves the piano cemetery. Her child’s steps knowing and not knowing. She meets her grandmother standing at the carpentry bench where I used to work and where Francisco works. Íris approaches and gives her her hand. My wife feels Íris’s little hand between her fingers, holding them.

Even without any pianos to repair, there were mornings and afternoons when I’d go into the piano cemetery to be alone. There were mornings when, summer or winter, the same light always came through the window, the same shade of dirty brown. The previous night I might have spent hours at the taberna , I might have argued with my wife. Slowly threads of the previous night would pass through my head — mists of alcohol dissolving, words or images of my wife that rose up suddenly. There were afternoons when I’d change my mind, when for a few moments I’d give up, but when, suddenly, straight afterwards, I’d believe with all my strength that I could change everything. And I’d look at the pianos, and I’d think.

I’d look at the dead pianos, I’d remember how there were parts that could be brought back to life inside other pianos, and believe that all life could be reconstructed in just this way. I was not yet ill, my sons were growing up and turning into the lads that I had been myself not long ago. Time passed. And I was sure that a part of me, like the parts of the dead pianos, would continue to function inside them. Then I remembered my father — his face in the photograph, the box of medals, his stories told in my aunt’s voice or my uncle’s voice — and I was sure that a part of him was still alive in me, revived each day in my gestures, in my words and in my thoughts. A part of my father revived when I saw myself in the mirror, when I existed and when my hands continued to build all the things that he — secretly, so close and so far away — had started. Then I thought there was a part of my father that would remain in me and which I would hand on to my children so that it should remain in them until one day they begin to hand it on to my grandchildren. The same would happen with what was only mine, with what was only my children’s and what was only my grandchildren’s. We repeated ourselves, and moved away, and we moved closer together. We were perpetual in one another.

One of those afternoons when I was sitting in the piano cemetery, alone, thinking, I heard the footsteps of the postman on the earth floor of the entrance hall. I came out, as though busy, quite normal, and received the letters in my hand — bills and an envelope with the name of my cousin: Elisa. The postman was talking about the weather, complaining about the cars. I looked at him, I replied only with yeses, I said:

‘Yes, right.’

I wanted him to leave, wanted him to leave me alone. I had never received a letter from my cousin before. I looked at the postman. I replied only with yeses. I squeezed the pack of letters in one hand. And I held my cousin’s letter carefully in the other.

Me, Marta, Elisa, Hermes, Íris, Ana, Maria, Simão, Francisco, Francisco’s wife, the son who would be born, Hermes — the weight of the gypsy’s body, the perspiration, the hot smell of the gypsy’s body — Íris, Maria, Marta, Simão, Elisa, Ana, Maria, Francisco, me, the son who would be born, Francisco’s wife, Francisco, Simão — the touch of the gypsy’s eyes, the fire in the gypsy’s hands, embers, flames — Maria, Marta, Elisa, Ana, Hermes, Íris, the son who would be born, Francisco, me, Marta — the gypsy’s skin slipping, the smooth skin — Maria, Simão, Francisco, me.

On the way from the workshop to Maria’s house, my wife wants to escape from remembering the gypsy and she thinks about us. Our faces and our names mingling with flames. She goes faster. It’s not long until Maria’s lunchtime.

I was left alone. I waited, until after a few quick footsteps, and went into the piano cemetery. And I didn’t breathe. I opened the envelope. I unfolded the sheet of paper. I ran my eyes over the lines that my cousin Elisa had written to me — straight lines. And greetings, and the signature, with broad round shapes — Elisa. Then, slowly, I put the sheet down on a piano and looked at it from a distance. I imagined my cousin sitting there, the corner of the sheet aligned with the squares on the tablecloth, the ballpoint pen the worn colour of objects that are valued but old. I held the sheet of paper again, as though I wanted or needed to confirm what was written there — she passed away last week, peacefully. I put the paper down again and thought about my cousin’s choice of words — passed away, peacefully. I compared the words with the images I recalled from the day I took a train more to learn about my father than to meet them. My aunt, who looked at me, who held photographs out to me, was dead now, passed away, peaceful. And I couldn’t help but imagine how that fat woman, that immense woman, stretched out in a dirty bed, had been washed, dressed in clean clothes, and finally presented with dignity. In just the same way I couldn’t help but imagine my cousin, beside her, standing, all alone, in clothes she had bought to wear for the special occasions she never had. I held the letter again, and read it again. Those written phrases were the only visible part of all the phrases that my cousin hid inside herself. They were the only evidence of her voice. I folded the sheet of paper and put it away in the envelope. As I did it, I discovered that my aunt truly had, in days gone by, been a little girl. My cousin, too, in other days, she had also been a little girl. And that was how I saw them — dead and abandoned little girls. That would be how I’d see them again, later, whenever I remembered them in my thoughts.

In the kitchen, a memory makes Marta smile. Everyone in the world recognises the sun. July. In the living room, Hermes is sitting with his hands resting on his legs. Without any help he is trying to understand mysteries. Elisa is tidying up the toys that Hermes has left disordered in the sewing room. It is Friday. The afternoon is taking its time to end. July — luminous calm.

The dogs bark. The dogs bark. Afternoon. Hermes, Elisa and Marta wait. Someone knocks at the door. Elisa goes into the hallway. She walks, with a thought suspended. She opens the door. A woman with brown eyes, made lighter by the dusk. A woman who is too straightforward. Marta comes into the hallway. She walks towards the door. Hermes comes into the hallway. Marta stops beside Elisa. Hermes walks towards the door. He stops beside his sister and mother.

The three of them look at the woman, who looks only at Marta and asks after her husband. She says his name. The first time I heard that name was in the kitchen of our house. At that time Marta’s husband was her invisible boyfriend and I was thinking about things that have stopped mattering. Marta has her arm resting on her son, but she doesn’t have the weight of the arm on him. Marta has a blue smock on her body. She has slippers on her thick feet with their thick toes. The woman is wearing a skirt and a fine blouse. Her hair is well coiffed. Marta looks at her and is surprised that she never imagined her like this. She is a woman like other women. She has eyes and a voice and dreams. She is concrete. She lives with the same fear. Marta feels a small shudder that she’s sure can’t be seen. Her voice is faint when she says her husband isn’t in.

Читать дальше