But life has been good to me. Paul and Kim, the American couple whose children I take care of four days a week, pay me more than a decent wage. I’ve become an expert in nursery rhymes and counting rhymes: ours, the English ones, and even a few in Dutch. The children know En ten tini, sava raka tini, sava raka tika taka, bija baja buf . And Eci peci pec, ti si mali zec, a ja mala vjeverica, eci peci pec . They know Rub-a-dub-dub, three men in a tub: the butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker . And Amsterdam, die grote stadt. Die is gebouwd op palen. Als die stadt eens om-meviel, wie zou dat betalen …. Paul and Kim never fail to introduce me to their friends and relatives: “This is Tanja, our babysitter. She’s wonderful with children. She really has a way with them….”

My mother is doing fine too, if “fine” is the word for it. She perks up whenever I phone. She tells on life the way children tell on one another: she pulls out her list of complaints and goes on about her diabetes (which she calls “the sugar curse”), her arthritis, the high cost of living…. She never asks about me: I’m just there to register the complaints. I’ve made peace with my role and grown used to our one-way dialogues. I’ve learned not to let it hurt too much.

Goran’s father is no longer with us. “They might as well have stuck him in a garbage bag!” said Olga, sobbing into the receiver. “A garbage bag!” He’d fallen into a coma, so she called for an ambulance, but the paramedics couldn’t get the stretcher into the elevator, so they had to wrap him in a blanket and carry him down all ten flights. He died in the hospital a few days later. She told me all about it when I phoned with my condolences. “Though it had to end somewhere,” she added in an odd voice, thereby putting a sad yet apathetic end to the incident.

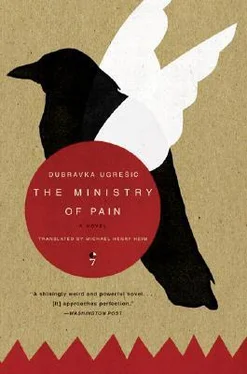

Ana survived her return to Belgrade by less than two years: she was with the Belgrade Television team that perished in the NATO bombing of the city. I’ve kept the letter she sent me several months after her departure. Along with a short note saying she had found a job and was doing fine, she enclosed a short composition entitled “Depot,” her late contribution to our imaginary museum of everyday life in Yugoslavia. It was a melancholy description of the place where the Belgrade tram lines come to rest, a description of the sounds, the sultry summer sunset, the smell of the dust-filled air. “Put it into our plastic tote, the one with the red, white, and blue stripes,” she wrote. I was touched by the sweet folly of the gesture. Geert decided to remain in Belgrade. I have no idea what he’s doing or how he earns his keep. He phones me now and then, and I can tell from his voice that I, a foreigner, am his only link to “home.” I am still at his address.

As for the rest of them, they seem to be holding their own. Ante still plays his accordion all over town. He’s at the Noordermarkt every Saturday. People toss their coins into a cap given to him by the fellow from Virovitica who has the hat stall there. All “our people” know him. Nevena has married one of “our” boys and has a daughter by him. She’s working at the Mercatorplein branch of the Rabo Bank. Meliha is in Sarajevo. She’s managed to reclaim the family flat and evict the people who had been living there illegally. Meliha’s parents will have nothing to do with the city: they haven’t been back once since moving here. Meliha is living with her Da  er , who has set up an NGO for “vulnerable people.” Mario has left the university and found work in computer graphics. He has a baby, too, a boy. Boban has joined a local Buddhist sect, shaved his head, turned vegan, and got himself on welfare. Only Johanneke has stuck it out at the university. Her elder daughter has run away. She’s in Bosnia with her father. Johanneke is devastated. Selim has gone super Muslim, hanging out with the Vondel Park weirdos, grumbling about how “us Bosnians gotta kick the shit out of them Serb bastards and then the Croats and then the whole Euro crowd, Yanks included.” Zole, who came to class only once or twice, has supposedly split for Canada, claiming to be a “double victim”—of Miloševi

er , who has set up an NGO for “vulnerable people.” Mario has left the university and found work in computer graphics. He has a baby, too, a boy. Boban has joined a local Buddhist sect, shaved his head, turned vegan, and got himself on welfare. Only Johanneke has stuck it out at the university. Her elder daughter has run away. She’s in Bosnia with her father. Johanneke is devastated. Selim has gone super Muslim, hanging out with the Vondel Park weirdos, grumbling about how “us Bosnians gotta kick the shit out of them Serb bastards and then the Croats and then the whole Euro crowd, Yanks included.” Zole, who came to class only once or twice, has supposedly split for Canada, claiming to be a “double victim”—of Miloševi  and of the NATO bombs. But a more likely version is that he got in with the local Serb mafia and split to save his skin.

and of the NATO bombs. But a more likely version is that he got in with the local Serb mafia and split to save his skin.

I had this all from Darko when I ran into him on a deserted beach near Wassenaar one day. It was surreal. I barely recognized him: He had a bronze tan and light blond hair, and sported a pair of chic sunglasses and a Walkman. And he was on a horse. He looked like a Calvin Klein model or, rather, a fragile version of same. He was taking riding lessons at the Wassenaar Equestrian Club, he told me. He had a friend, a successful American businessman, and hung out with the gay crowd. Except now he’d left the low life — which he’d always been open about — for a house in Reguliersgracht: Thanks to the friend who’d blown a cool million on it. That’s right — a million dollars, two million gu  e ….

e ….

“I’ve discovered I love riding,” he said. And giving me a soulful look, he added, “Sign up for a course, any course — yoga, salsa, whatever — I tell everybody. As long as it’s physical, you get a lot out of it.”

“I’m taking Dutch,” I said.

“Good for you!” he said, as if talking to somebody somewhere else.

Just then I caught my reflection in his sunglasses and a chill ran up my spine: there were two faces glinting in the lenses, and neither was mine.

But most incredible of all was Igor’s story. He’d gone off the deep end, people said. First he got a job as a translator at the Tribunal, where he wasn’t the only member of our gang to be thus employed, by the way. But he got himself fired when he stopped showing up for work. Then one day he was found — found himself might be closer to the truth — at some airport or other in Calcutta, Kuala Lumpur, or Singapore. They said he was suffering from a post-traumatic syndrome with a great name, the musical name of “fugue”: dissociative fugue, to be exact. These fugues are apparently brought on by a sudden trip. They last anywhere from a few days to a few months and trigger a total blackout, during which the “fugued out” have to manufacture an identity: they have no idea who they are or where they’re from. And when they go back to their former lives, they have no idea what they went through in their fugued-out condition. It is a completely crazy lost-and-found disorder nobody’d ever heard of before. Some psychiatrists claim that the fugues don’t just happen, that they’re set off by drink. Maybe so, but Igor didn’t remember having been a drinker. Nobody knew where he was or how he was making ends meet. He might even have gone home. As for the others, they’d gone their separate ways. They’d lost touch.

“By the way,” Darko said in a voice a bit too cheery, “I’ve made another discovery.”

“Namely?”

“Opera!” he said, pointing to the Walkman. “I’m wild about Verdi.”

He paused and slumped ever so slightly, a fine shadow crossing his delicate, pretty-boy face.

“That time with Uroš…” he said haltingly, as if spitting sand from his mouth, “after the dinner, when we celebrated your birthday, remember?”

“I remember,” I said.

“Well, I walked him home, and we…horsed around a little…. Uroš wasn’t gay…But we were drunk….”

“Why are you telling me this?”

He shrugged his shoulders.

“Don’t know…. It’s been bothering me forever….”

Читать дальше

er , who has set up an NGO for “vulnerable people.” Mario has left the university and found work in computer graphics. He has a baby, too, a boy. Boban has joined a local Buddhist sect, shaved his head, turned vegan, and got himself on welfare. Only Johanneke has stuck it out at the university. Her elder daughter has run away. She’s in Bosnia with her father. Johanneke is devastated. Selim has gone super Muslim, hanging out with the Vondel Park weirdos, grumbling about how “us Bosnians gotta kick the shit out of them Serb bastards and then the Croats and then the whole Euro crowd, Yanks included.” Zole, who came to class only once or twice, has supposedly split for Canada, claiming to be a “double victim”—of Miloševi

er , who has set up an NGO for “vulnerable people.” Mario has left the university and found work in computer graphics. He has a baby, too, a boy. Boban has joined a local Buddhist sect, shaved his head, turned vegan, and got himself on welfare. Only Johanneke has stuck it out at the university. Her elder daughter has run away. She’s in Bosnia with her father. Johanneke is devastated. Selim has gone super Muslim, hanging out with the Vondel Park weirdos, grumbling about how “us Bosnians gotta kick the shit out of them Serb bastards and then the Croats and then the whole Euro crowd, Yanks included.” Zole, who came to class only once or twice, has supposedly split for Canada, claiming to be a “double victim”—of Miloševi  and of the NATO bombs. But a more likely version is that he got in with the local Serb mafia and split to save his skin.

and of the NATO bombs. But a more likely version is that he got in with the local Serb mafia and split to save his skin.