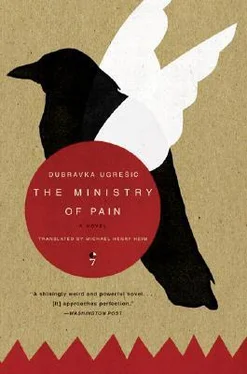

O mirrors of horror! Show scenes without gallows or noose! “Blood! Blood!” screams my blood in this land of Croatians ill used.

Shit!

But onward. To the ten percent belonging to what I would call the megalomaniac or me-me-me poems, poems where the guys talk one-on-one with the stars, the universe, like “If man you be, walk tall beneath the sky”—that shit. Poems where every man’s a fucking superman.

Okay. Fine. Next category: the twenty percent that sing the beauties of nature, you know, the seasons, rainfall, crap like that. You’d think they were a bunch of — what was the name of that Serbian weatherman? — right, a bunch of Kamenko Kati  es. Our freaks are into flora a lot more than fauna. True, I did find one poem about a calf, but I didn’t get it till the end. At first I thought it was about this hot little number — the language was nice and sexy — and then in the middle of it all comes this line about dung…. But to get back to the flora. There were all kinds of poems about fucking trees — aspens, willows, poplars, oaks. After all the horror stuff I was surprised our guys had a thing for flowers — lilies of the valley, pansies, roses, cyclamen. I didn’t think horror and horticulture went together. Though one guy had something about bloody cyclamen.

es. Our freaks are into flora a lot more than fauna. True, I did find one poem about a calf, but I didn’t get it till the end. At first I thought it was about this hot little number — the language was nice and sexy — and then in the middle of it all comes this line about dung…. But to get back to the flora. There were all kinds of poems about fucking trees — aspens, willows, poplars, oaks. After all the horror stuff I was surprised our guys had a thing for flowers — lilies of the valley, pansies, roses, cyclamen. I didn’t think horror and horticulture went together. Though one guy had something about bloody cyclamen.

How much does that make altogether? Ninety percent? Okay. So then I went through them with a fine-tooth comb on the lookout for sex. Well, you could’ve knocked me over with a feather: our guys don’t care shit about sex. It jumps right out at you. No calculator necessary. Believe me, the only time they can write about a woman is when she’s dead and buried. It’s like they can hardly wait for the gal to bite the dust so they can write a poem about her. The sadder the better. Like the Dalmatians, for Christ’s sake. You know the poem:

I saw you last night. In my dreams. Sad. Dead.

In the fated hall midst an idyll of flowers.

On a lofty bier midst the throes of the candles.

Of course you do. We had to learn it in school. Well, the same necrophiliac wrote:

I know not what thou art: art thou woman or hyena?

Shit! Did that guy get my goat! I mean, what’s the point if you can’t even tell a woman when you see one. And then there was the guy who couldn’t find a place to bury his broad (“Where can I bury you, O my love, now that you’re gone?”) and the guy — the more I read, the more they pissed me off — who was away for so long that by the time he got back his girl had kicked the bucket:

But when I arrived,

I found you no more.

What did he come back for, the shithead? And then there was another one we had in school, remember?

Love may yet come, befall us yet, I say,

But do I wish it or wish it away?

That always made my blood boil. Your problem ain’t whether you want to, pal; it’s whether you can! So pack up your wares and get a move on. I’m not buying.

They’re a bunch of sickos, our poets. And not only the ones in the anthology. There hasn’t been a sound mind among them in the past two hundred years or however long they’ve been at it. Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Macedonians — it makes no difference. Old farts all. You don’t need a calculator to tell you that.

UROš: I WISH I WERE A NIGHTINGALE

During our second year in elementary school the teacher assigned us a composition about Tito. Tito had had a leg cut off, she told us, and was recovering from the operation. It would make him happy if we wrote something nice. I wrote I wished I were a nightingale so I could fly to Comrade Tito’s hospital bed every morning and wake him with my song. The teacher praised me to the skies and read my composition to the class. My classmates made fun of me. They called me the nightingale. “Hey, here comes the nightingale,” they would shout with a guffaw. When my family heard about the composition, they made fun of me, too, especially my old man. Then, not long afterward, Tito died, and my old man cried and the whole family sat in front of the TV for the three days of the funeral and cried. The thing that impressed them most was all the foreign dignitaries attending the funeral. “All those famous people,” my old lady said. They had a good time pointing out the announcers’ mispronunciations of the statesmen’s and celebrities’ names. But when I said that Margaret Thatcher’s name is Thatcher, not Tratcher, my old man said, “That’s enough out of you, Nightingale. Go and get me a bottle of beer from the fridge. And, mind you, don’t drop it from your beak!” Which got a big laugh out of everybody.

Yugoslavia was a terrible place. Everybody lied. They still lie of course, but now each lie is divided in five, one per country.

I think it best to state straightaway that the northern Netherlands have always made me feel a certain Angst, which I write with the capital letter the German requires, as if in the early doctrine of the Naturphilosophen it were one of the basic elements, like Fire and Water, of which life on earth is constituted. The capital letter gives one the feeling one has been placed in a black box from which there is no easy escape.

Cees Nooteboom

Amsterdam isone of the most beautiful cities in the world. Overused a platitude as it is, I would have no hesitation putting my name to it, and with nary a blush at its banality, were it not for what it leaves out: a sensation, an almost physical sensation of absence about the city, a sensation that occasionally pursued me and whose source I was unable to pinpoint.

Roaming through the city, I would pass through a number of olfactory zones, urine ceding to the mould that grazed my nostrils as I ran down a flight of stairs, the mould ceding to the rancid oil that wafted from the cheap seaside food concessions and lodged in my hair, the oil ceding to the human sweat that clung to me as I made my way through the crowds, the sweat ceding to the heavy, sticky aroma of hashish. The ever present physicality all around me had no power to arouse; it produced the same impression as the eccentric old man who did circus tricks on a tightrope in the middle of the Leidseplein stark naked. That naked superannuated human body twisting and turning on a rope was a grotesque example of the city’s incongruities.

Detail after detail threw me off guard. I was constantly confronted with a certain dualism: everything seemed to go hand in hand; each plus had its minus. The absence of beauty took the classic forms of ugly civic sculptures, the iron fly lying on the Haarlemplein asphalt, the metal caterpillars crawling through the Leidseplein’s lawns, the miniature, rubber-ball-sized busts sticking up out of the wet grass in park after park. But beauty, too, was present, and it, too, took classic forms: museums, patrician houses, canals, reflections….

Besides the first platitude I often heard another, namely that “Amsterdam is a city of human proportions.” For me it had the proportions of a child. Shop windows in the red-light district displaying live dolls for grown-ups, porno shops decked out to resemble toy shops, kindergarten-like coffee shops with plastic mushrooms “growing” at the entrance and Dam’s theme-park attractions. It’s not that this urban infantilism is subversive or derisive — it would appear to have no ulterior motive whatsoever; it’s just that it has turned Amsterdam into a kind of melancholy Disneyland. I often experienced a vague sense of shame as I walked through the city, playing its pornographic game and wondering whether I wasn’t the only one who perceived it as such.

Читать дальше

es. Our freaks are into flora a lot more than fauna. True, I did find one poem about a calf, but I didn’t get it till the end. At first I thought it was about this hot little number — the language was nice and sexy — and then in the middle of it all comes this line about dung…. But to get back to the flora. There were all kinds of poems about fucking trees — aspens, willows, poplars, oaks. After all the horror stuff I was surprised our guys had a thing for flowers — lilies of the valley, pansies, roses, cyclamen. I didn’t think horror and horticulture went together. Though one guy had something about bloody cyclamen.

es. Our freaks are into flora a lot more than fauna. True, I did find one poem about a calf, but I didn’t get it till the end. At first I thought it was about this hot little number — the language was nice and sexy — and then in the middle of it all comes this line about dung…. But to get back to the flora. There were all kinds of poems about fucking trees — aspens, willows, poplars, oaks. After all the horror stuff I was surprised our guys had a thing for flowers — lilies of the valley, pansies, roses, cyclamen. I didn’t think horror and horticulture went together. Though one guy had something about bloody cyclamen.