A quarter year of unbroken booking and I begin to acquire a layman's understanding of mutation at the molecular level. Information in the nucleic acid string is carried by the order of base pairs, the sequences of genes. The sum of gene messages — the tangled program of genotype — expands from single egg to runaway cell civilization. The same linear long set (more possible messages than atoms in the universe) chemically juggles the whole fantastic hierarchy until at last it impairs itself with old age and dissolves.

I have a rough analogy of the master plan. Each DNA spiral is two chains. The rules of complementary base pairing and the undulating regularity of the molecule give each half-helix the ability to act as imprint for the whole. This trick of molecules to sort, arrange, and assemble odd parts of random world into copies of themselves arose spontaneously, from the early chemical mix and the energy of an electrical storm. Miller produced the essential building blocks by exposing hydrogen, methane, ammonia, and water vapor to electrical discharge and ultraviolet light. By 1956, Khorana had synthesized polynucleotides in the lab. Ressler was then younger than Todd is now, and I was a toddler.

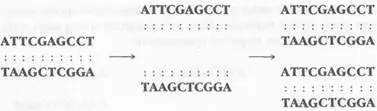

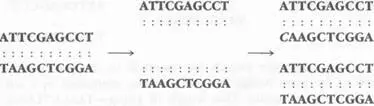

Replication is simple enough to model with a drawing. The split strands separate, each becoming a template for duplication:

The two daughter strands are identical 10 the parent. One third of the great bridge: Mendel's factors, embodied in a self-perpetuating molecule. That length of string — TAAGCTCGGA, plus hundreds more bases in strict sequence — encodes particular inheritable traits, say smooth seed or wrinkled. Molecular neo-Mendelism is consistent with the rules of gross segregation and assortment, requiring no metaphysical rules — just the constraints laid down by chemists: purine with pyrimidine, electrons in the lowest energetic state.

But that "just" is enormous. Genetic mechanism contains nothing transcendental. Cell growth, organism development conform to the principles of undergrad chemistry. The grammar does not change from generation to generation — only individual sentences do. A simple lookup table, one or more triplets of nucleotides to each amino acid, is universal for all life. Yet to get hold of this, to learn what it means, I must look into a creation story more miraculous than any human genesis myth.

I try to imagine a machine that, through a design stumbled upon by trial and error, has developed the ability to sniff out compounds that it then strips and welds to create another such machine. I cannot. Then I can: deer, euglena, snowy egrets, man. Self-replication is the easy part of the story, the simplest way that the purposive molecule arranges its environment. The sequence of bases in a gene is nothing in itself. Not phalanx, strut, tooth, claw, or eye color. Merely a mnemonic for building an enzyme. The enzyme does the work, steers the shape and function of the organism. The gene is just the word. I must follow it down, make it flesh.

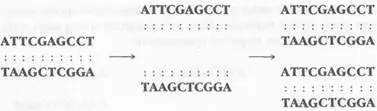

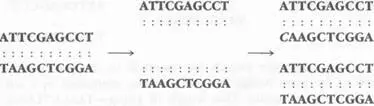

I begin to understand how the real power of this self-duplicating machinery lies not in how perfectly it works but in how, incredibly rarely, it fails to work perfectly. If inviolable process allowed the magic crystal to seed itself in the first place, occasional fallibility permits life to crack open the sterile stable of inorganics and scream out. On the order of once every million replications, something goes wrong. Perhaps a base in a daughter string pairs with a base other than its required complement:

i

i

A mistaken daughter: CAAGCT— Who knows what this new chain might mean? Slightly different from its parent, it may produce a different enzyme, an unexpected convolution in the unfolding ear. I draw the repercussions, repeat the replication process with the impostor cytosine going on to pair with its normal mate, guanine. One of the four granddaughters differs from all the other copies. Noise invades the system. One bad pairing alters the gene's original message. Unlike the surnames of American daughters, the change need not be lost in generations. This aberrant offspring— with a new arsenal of enzymes — may be more successful at making further copies than her dutiful sisters, though the odds against this rival the odds against mutation in the first place.

Now I must link Darwin and his riot of proliferating solutions to that one-in-a-million molecular mistake. I must trace how chance static — a dropped, added, or altered letter in the delicate program — can possibly produce the mad, limitless variety of the natural history plates. That forethought and design could come of feedback-shaped mistake is as unlikely as the prospect of fixing a Swiss watch by whacking it with a hammer and hoping. The element I lack is the odd eon. I have eight months. The world has all the time in the world.

Whatever works is right, worth repeating: not much of a first principle. How can blind unplan produce a string thick with desire to reveal its own fundament? Where is the master program he was after? Somewhere in the self-proliferating print, the snowy egret, a keyboard that plays itself when you hit the right notes. The theme Ressler hoped bitterly to forget urges me on, whispering in enzymes to rebuild the buzz all around him.

The Question Board

Q: There is an enclosure with ten doors. When one is open, nine are shut. When nine are open, one is closed.

A: Once we held metaphor cupped in our hands. But it's foreign to us now, the riddle, lost to our repertoire except in the short span of childhood and the handful of adult months when we recover a glimpse of where we're going. We can predict, measure, repeat our results better than anything that has ever lived on earth. But we cannot answer this simplest of games.

Its beauty is verbal ingenuity: how well the hidden comparison fits. The sorrowful romance of three lines says more in hiding than it would by spelling out. But what good are riddles? Why bother with them? One might as well ask why bother with growing old. They are ways to begin to say what wonder means.

But my lost friend, this one is easy! One needn't be Solomon to solve it. When the umbilical is open, all other ports are still sealed. But cut the cord, and the stitch in time opens nine. You have one, proved by your effort to escape it. I have one, a full complement of symmetric parts; you knew it intimately once. Forgotten already? There is an enclosure with ten doors. We are each locked up in one for life.

J. O'D., October '85

A Day Without the Ever

Todd would choose mornings like this to show up downstairs, ring his private signal — a monotone but unmistakable rendition of "La donna e mobile" — and insist that I come out to play. "All systems go. The dissertation's in hand. Ready for committee in six weeks," he would say, tossing me a softball when I opened the door. "How's about a little fungo?" Unflappable in the face of adulthood. This morning, I'd close his batting hand in the doorjamb. Just once, I'd leave him something he might feel for longer than the usual afternoon.

The date on his Greetings from Europe leaves him at most a few weeks to have stood still and grieved. He never had any trouble feeling deeply. Just broadly, for any length of time. Ressler's lecture notes will never be made good. The ludicrous old stereo has been farmed out to Goodwill. The rooftop garden in Lower Manhattan that kept us in tomatoes all summer has run to seed. And Franklin's moved on to the next feel.

Читать дальше

i

i