Richard Powers - Gold Bug Variations

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Richard Powers - Gold Bug Variations» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1991, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gold Bug Variations

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:1991

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gold Bug Variations: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gold Bug Variations»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gold Bug Variations — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gold Bug Variations», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The quizz-show scandal breaks. Jack Benny admits to being forty. A leading manufacturer brings out a nontoxic floor wax, to save infants that lick their way across the kitchen. According to Time, eleven thousand new "citizen-consumers" are born every day in the U.S., adding a city the size of Norfolk, Virginia, every thirty days. "A new wave of opportunity coming."

Science too can't help but join the footrace. The accidental clarity that Ressler and his love stumbled upon over the phone remains solid, even in the unforgiving light of following days. Botkin declares the proposed angle as right as an inevitable passacaglia. They sit in her office listening to Fauré, Franck, drawing up the apparatus needed to confirm his serendipitous insight.

In barely controlled excitement, Ressler does the week's summary for Cyfer. He begins all the way back in the uncontestable: the double helix. Not even Woytowich holds out against the model any longer. He has just become a father — an architectural marvel named Ivy. The impossible reprieve leaves him open to even the most outlandish proposals about life's generating plan. Taylor's radiographs, too, transcend disagreement, proving that DNA replicates by that classic postwar cure-all, political partition. One message splits into two; two halves each restore the one message. The simplest form of molecular baby-making: divide and regenerate.

Adding a demonstration of Mendelian inheritance for mutations, Ressler presses up against the last unequivocal certainty. This double-twined ribbon pastes up, from its internal library, the army of proteins that pump, breathe, inflame, hoist the whole organism. The rest is tentative, beyond the limits of current, territorial waters.

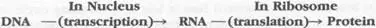

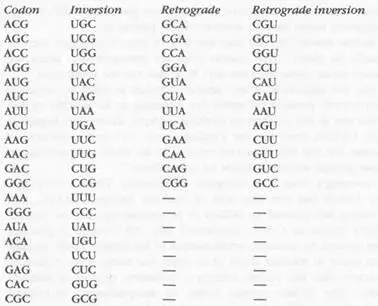

"Our own work," Ressler casts a cold eye at Ulrich, "elaborates the decoding parameters: triplet, colinear nonoverlapping, unpunctuated bases. We know that DNA never leaves the nucleus. I submit that it sends out a courier, a single-strand RNA molecule templated on its surface, a plaster-cast of the recipe. This messenger strand carries its transcription of a base sequence — call it a gene, for old times' sake — to the ribosomes, where protein synthesis takes place." He draws a freehand philosopher's stone on the blackboard:

"OK," says Ulrich. "Two separate processes. One directly templated, one read and assembled. Ribosomal RNA promoted to translator, not message. Valuable," the chief concedes. "But does it get us any closer to reading the bugger?"

Introducing a new, ephemeral, RNA messenger — itself a single-ribboned series of four bases, with uracil substituting for the thy-mine in DNA — doesn't change the informational nature of the problem. From a cryptographic vantage, it makes no difference whether the code word is the RNA simulation or its DNA original. They still track the old, elusive pattern. So despite the opportunity staring him in the face, Ulrich insists that codon assignment is more a symbolic problem than a chemical one. He fails to see that Ressler's clarification gives them an experimental wedge, a way of simulating nature's own mechanism, letting the cell solve the problem for them. Instead, Ulrich is preoccupied with his own pronouncement: the discovery of a way of juggling the letters to produce a pattern so satisfying that it must be correct.

Ulrich announces, in competition with Stuart's unsubstantiated diagram, that he, Lovering, and new conscript Woytowich may be in a position to land the Big One. "The closer we get, the better it looks. DNA splits loose along the inside seam to present the base sequence. Either edge might code for the protein, so any codon and its complement on the anti-gene would stand for the same amino. The triplet AGU thus codes for the same thing as its Chargaff anticodon UCA on the other strand. Two chains, two directions, so to the synonyms AGU and UCA, we can add UGA and ACU. Four words under the same thesaurus heading."

"Treatment by retrograde and inversion," Toveh Botkin mumbles, troubled. "Bach was fond of putting fugue subjects through both." So was this fellow Schoenberg, thinks Ressler, who's done his homework on the matter. But that proves nothing. He's nonplussed and can do nothing but keep still and follow the working-out.

Ulrich lists the sixty-four-codon catalog according to groups of shared degeneracy, the plan growing increasingly obvious:

"All sixty-four permutations. The set contains twelve fourfold synonyms and eight twofold synonyms." With a touch of showman's pause, Ulrich says, "Twelve plus eight equals our magic number." The pattern is stunning in its own, horrific way. The rationale for construction seems at least reasonable, and the numerology is perfect. That Ulrich has leapfrogged empirical constraints to get there seems temporarily defensible.

"But it's all wrong," Ressler whispers, glancing at Botkin for support. He's afraid to appeal to Koss, afraid to look at her in public for fear that her ephemeral face might make the day's pragmatics too much to bear. But it's Koss who comes to his aid. She objects, grounded in the best literature, to the idea that the complementary strands are being read equivalently. For all her substantiated accuracy, the facts wash up impotently against perfect pattern.

That Ulrich's subdivision of sixty-four triplets uncannily produces a hidden number equal to that of the essential amino acids carries the surprise significance of arithmetic. He is under the spell of physics, where the pursuit of fundamentals pares back a mass of data to simple, elegant expressions. It seems safe to assume that cellular mechanisms, carded back to their core, are also driven by symmetry. But it's not safe; safety and life science are incommensurate. That one can derive twenty from sixty-four with pretty, reciprocal twists may be nature's sheer perversity.

Botkin lowers herself into the line of fire. "Grammars are not usually so clean." Her cheeks contract bittersweetly: don't we always mean more than we say? Why not the we within us?

But the objection of one senior member is offset by another. Woytowich, revived by infant Ivy, wanting to be worthy of her when she is old enough to evaluate fathers, throws his hopes in with Ulrich's dash for the cymbal crash. "It's not evidence, of course; but the fit's attractive enough to do some stat analysis on those groups we think might be equivalents."

Lovering's vote is a foregone conclusion. There's only one way Ulrich can run that sort of analysis: through ILLIAC. And Lovering has proved so skilled at programming that he has replaced Stuart as Cyfer's fair-haired boy. All Ulrich's hopes are now pinned to numeric confirmation of his simple table. Ressler tries again to interest them in in vitro, but these three refuse to concede that the codon catalog is arbitrary, devoid of internal order. The debate comes down to temperament, individual hobby horses. What each feels ought to be true. The team splits down the middle — gnostics versus nominalists, formalists against functionalists. They forget the first article of scientific skepticism: meaning always reveals pattern, but pattern does not necessarily imply meaning.

Ressler cannot fault Ulrich for leaping to the beautiful conclusion. Would Stuart have begun in science if he wasn't predisposed to believing that what lay behind common sense was more beautiful because more objectively indifferent, dense, feverishly specific? Ulrich sends them off with his blessing: "Both parties' results to be continuously exchanged, of course." Yet Ressler knows he will be out a fellowship come spring. He is resigned, for his own sake, to losing everything, every professional advantage, for a glimpse of the demonstrable. Only now, he has dragged Botkin and Koss into the breach with him. Against their careers, he has only a vague plan: learn the trick of the cell-free system.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gold Bug Variations»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gold Bug Variations» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gold Bug Variations» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.