All through the summer, words come back to you. At meals, or during your half-hour sprints along your oval track, or in the middle of the morning bathroom ritual, now trimmed back to a frenzied seven minutes. Forgotten vocabulary, sometimes in your mother's voice, sometimes in the voice of those grandparents, fictional to you except for two short childhood trips Stateside when the Brits still pumped the oil and the Shah still issued the travel visas. Words return. The names of foods. The primary colors. The numbers from one to ten.

More than words: chunks of your mother's favorite stories, in translation. The one about the white-haired baby who grows up to be a mighty king. The one about a flock of birds who set out to find the fabulous Simurgh. They cross the seven valleys of Journey, Love, Knowing, Detachment, Unity, Bewilderment, and Annihilation, the thirty straggling survivors hanging on just long enough to discover, or rather to remember, that Simurgh means nothing more than "thirty birds."

Your cell is a nave. A ship, a dinghy adrift on the currents of wrecked empire. You lie back in the stern, shackled to your radiator, this room's rudder. Open seas leach you. You drift on the longest day of the year, bobbing near madness, the black overtaking you, infinite time, unfillable, longer even than those childhood nights when your own prison bedroom ran with a dread so palpable that sleep seemed certain death and death far better than this standing terror.

And then that frightened, fleshy face is there, next to yours, laughing in the dark.

What in all the world does a child have to be scared of? The old Persians, your people, called their walls daeza. Pairi meant anything that surrounds. See? Pairi daeza. You have a wall running all the way around you. That, my little Tai-Jan, is the source of Paradise.

perfects itself. You lie back against the wall, as far from the radiator as the links of chain allow. Bone-cold all winter, the machinery now comes alive, eager to add its joules to the summer inferno.

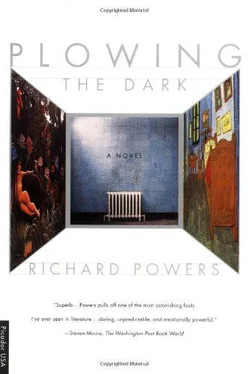

You close your eyes and will yourself into another climate. The volume materializes in your hands, the weight, the heft, the binding's resistance. You turn the treasure over and over, resolving the details down to the publisher's insignia on the spine. Through your eyelids, you inspect the cover illustration. Your read the blurbs on the back, the synopsis, the ISBN, all the precious trail marks you once squandered so profligately when they were yours to waste.

Each page of front matter passes one by one under your sentry fingers. Hours may dissolve, just playing with the stiffness of the paper, before you get to the actual first sentence. Lord Jim, the forty-four-point Garamond Bold announces to your hushed house of one. And again, in thirty-six-point type, on the next wondrously superfluous page. Or Great Expectations. Every menu name becomes a whole banquet where you might dine out eternally, for free.

You reach the opening sentence, the fresh start of all things possible. Modestly boundless, it enters bowing, halfway down that first right-hand page. You lie back against your paradise wall, your pillow. You make yourself a passive instrument, a seance medium for these voices from beyond the grave. Politics has taught you how to read, how to wait motionless, without hope. To wait for some spirit that is not yours to come fill you.

My name being Phillip. No: my father's name being Pirrip, I called myself Pip. Something about a graveyard, five little stones as visible as the door of your cell, the markers of brothers who gave up on making a living exceedingly early in this universal struggle. Every turn, every further constriction in the plot — yours or the author's — makes it easier to keep to the general contour. Where you cannot recall a scene, you invent one.

You recognize that underclass orphan making his way in an indifferent world. He was the first present you ever gave her. A fake heritage hardback edition that actually sold for $12.95 in the Cut-out Classics bin at both of the mall bookstore chains. Gave it to her for her birthday, half a year after you started going out. Back in that year when you were still trying to feed her all your favorites, to hand over to her all your secret treasures. Love me, love my childhood. Love my books. Maybe you meant an element of remedy in the gift. It had shocked you when she told you she'd never read it.

She tore at the wrapping, excited. But she cried when she saw the contents. The price, you thought at first. Gwen knew prices, even of things she never bought. You must have come in a level or two below where she'd expected. Hurt, you bit back. Said that you'd make sure to get something more expensive next time.

But no. That wasn't it, she sobbed. A book was not a personal gift. People gave books to colleagues, to acquaintances, not to their intimate partners. You might have given this to anyone. It didn't say you and me. It didn't say, You are the only person in the world 1 could have given this to.

You tried to explain. It did say you. It did say me. This was a story that you'd read four times over the course of your life, one that had meant something different each time you'd read it. It did say you and me. It said you wanted her to know the things that you knew. You couldn't have given it to anyone else, you lied. She didn't need to know who else you'd once tried to give it to.

Appeased a little, she flipped through, smiling bravely at the opening pages for your benefit. She patted the book. Said, Thank you so much. I'll let you know what I think. Slid it carefully into the appropriate place on her shelves, then came and dragged you off to her bed, where she ravished you, abdomen slapping against abdomen in such fury that you lost yourself in her punishing metronome, feeling in that impact the force of the correction she needed from you.

Later you discovered, in Gwen's refrigerator, a fresh pot pipe carved out of a golden delicious apple lined with a little tinfoil. A little private birthday celebration, prior to your arrival, that she'd felt no need to tell you of. Her tears, forgiveness, ecstasy, and fury: all artificially enhanced, with you, as usual, the last person to dope things out.

The book stayed on her shelf for the next six years. To all evidence, she never touched it again except when she dusted. Never tried to read another word, straight, high, or otherwise.

The fruit bongs appeared and rotted, without fixed season, front-runners in a suite of little secrets, the extents of which you could only guess. She never much tried to hide them, but neither did she ever bother to announce their appearances. You offered to smoke with her, some weekend evening, when the two of you weren't doing anything the next day. Tai-Jan! Gwen said, in her favorite imitation of your mother, who exercised some fascination on her you never wholly understood. My little pragmatic moralist wants to get stoned with me?

It seemed worth not letting her get to you. Worth waiting her out. Worth trying to be the safety net, the model, the pillar of trust that she'd never before received. But you felt something forbidden, too, more than a little prurient, in the notion of getting lit with this woman, of tumbling into a web of shared sensation, all gatekeepers gone. Getting inside that cloud of private lust you sometimes glimpsed through the frosted-glass window of her skin.

What's your favorite book? you ask her, your brain pinging down a chain of associations, the night you do at last light up together. The melding that you'd hoped for comes off, at best, as a self-conscious swap of concessions.

She stares at you too long for it to mean confusion. It takes you about three lifetimes to realize she's mocking you. Her barricades and burning-oil look: What planet did you say you're from? Favorite trick to knock you back on your heels. Jockeying, even now, while the two of you share this brief vacation from yourselves.

Читать дальше