Oh, my forefathers… these are the men who went before us!

the colonel could not understand what Amir was saying. He was standing in front of his father, holding the pick and shovel on his shoulder like an old gravedigger. the colonel looked at him and Amir glanced back at his father. We have nothing to say to each other. Although we belong to different generations, we have both witnessed the same things, so we are now as one. Except for one thing, which I hold dear, but do not have the courage to admit to…

the colonel got up, not caring that his clothes were all stained with blood. He set off at an easy pace, shoulder to shoulder with his son. The sound of their footsteps was the only sound in the square. They stopped at the side of the square. It was as if they had both agreed to go their own separate ways.

In the Traditions of the Prophet it is decreed that corpses should not be buried at night.

Amir headed off in the direction of the cemetery, nonetheless. the colonel watched his son as he disappeared. He did not give a moment’s thought to feeling any sympathy for Amir, for he had plenty of other things to do now.

“I must get on.”

The alleyway was completely lit up by the shrine to Masoud. As he passed it, the colonel realised that he was still clenching his left hand into a tight fist. He relaxed it. The 35 toman notes in his hand were damp with sweat. He laid them, all screwed up, at the foot of the shrine to his Little Masoud. “I can’t stop, my boy. I’ve got to go home and see to your sister’s canary.” He knew that if he let the bird out of its cage, where it had lived all its life, it would not be able to fly away, let alone survive. But he would rather do that than leave it to a living death in its cage. 67

He went straight up the steps into the corridor to open the cage. But as he did so he heard the mewing of the old black cat by the pond. He stopped to look at it. The cat looked back at him. He stamped and shouted, trying to shoo it away, but the cat refused to budge. It seemed to him the cat was quite shamelessly letting him know that it was just waiting for Parvaneh’s canary to come out so that it could gobble it up.

the colonel would have cheerfully killed it, but he thought he ought to have a look at the canary first. He crossed the verandah and went into the passage, switched on the light and walked up to the canary’s cage, which hung on the wall. No bird. He could not believe his eyes. He took the cage down and held it to the light, but the bird was gone.

“I’m so ashamed of myself, colonel. You should treat me as you would your son. I… I’ve eaten it, but it was already dead.”

It was the cat speaking, or so it seemed, with its mismatched eyes… or was it Abdullah? the colonel wasted no time dwelling on what might have happened to Parvaneh’s dead bird. With a venomous “You’re welcome to it!” he went out on to the verandah. He felt like stopping there for a while to breathe in the fresh air after the rain and recall that one day he had seen the sun setting over the ochre-coloured tin roof after the rain. He stood there with his arms crossed and thought that — hoped that — tomorrow would be a sunny day, like the day when they had brought home Mohammad-Taqi’s body. He thought how lucky were the people who would still be alive tomorrow. He did not begrudge it to them for a moment, or wish that he was going to be alive the next day. No, he thought, why should he spoil the end of his life by letting envy of other people get the better of him? No, life’s tribulations may open one’s eyes and ears and torment one’s soul, but they can also purge it of narrow-mindedness. And enjoying life makes death seem young and beautiful…

In these final moments, this thought took the stoop out of his back and he stood up straight and took a deep, delicious, breath of the air after the rain. No, I never wanted to go out with a whimper. I refuse to go quietly, not after all this.

He would have to take a shower and have a shave, brush his hair, and put on his old uniform, I’m a soldier, damn it! He was not going to forget his old standards now. He attached his aiguillettes, took his field boots out of the suitcase, polished them up and put them on. His insignia of rank had been stripped off when he was cashiered. He felt now that he had somehow pre-empted death by cleansing his body of all its slimy, grubby traces. He was purged. He just needed to dust off his beloved old setar and leave it hanging on the wall as a memorial.

I’m sure someone’ll play it again one day. He took his sabre down off the wall, wiped the dust off it with the back of his hand and tested its bright, shining blade with his finger.

Before I die, I must turn on all the lights in the house. He wanted the house to be ablaze with light. It was time to go. He was turning on all the lights in his house, in all my children’s rooms, as well …

He set off, picking up Amir’s will from under the sugar bowl on the table as he went. He tried to read it, and also to remember what he himself had written: “If those who are to come were to take the time to pass judgement on the past, in all likelihood they would say: ‘Our forefathers were powerful and impressive men, who sacrificed themselves to the great lie in which they fervently believed and which they spread. And the moment they began to doubt their beliefs, it was off with their heads! No doubt the bazaar merchants, businessmen and wheeler dealers among them will end up with the view that we would all be happy if we could just elect to be ruled by the least arbitrary of the thugs amongst us.’”

He put the sheet of paper back under the sugar bowl and, once more, held his sabre up to the light and studied its flashing blade. Running his freshly cleansed fingers along his jugular vein, he stepped out onto the verandah.

Now, have I turned on all the lights in the house? Yes, I have…

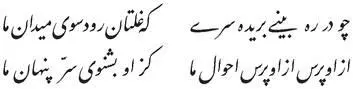

Ever after that rainless night, the street people and the bazaar folk heard the strumming of an old setar reverberating in the darkness of the alleyways. They said that in the dead of night one saw a man roaming the narrow little streets, holding a lantern in his hand as he chanted these ancient lines:

If you see on your way a severed head

Tumbling along to that square of ours,

Ask it, just ask it, how we all fare;

It will tell you that buried secret of ours!

Glossary of Names and Terms

Amir Kabir, Mirza Taqi Khan : major reformer and prime minister of Iran under Naser ad-Din Shah from 1848 to 1851. He established new ministerial departments, reorganised the financial system, founded the country’s first newspaper and first modern university and introduced compulsory vaccination against smallpox. In 1851, he was accused of conspiracy, dismissed from office and sent into exile in Kashan where, at the Shah’s instigation, he was murdered the following year in a bath house. Amir Kabir is widely regarded and revered as the founder of modern Iran.

Amoghli, Heidar Khan : leading member of the Communist Party of Iran, which was founded in the northern port of Bandar-e Anzali in 1920. Founder of the short-lived Gilan Soviet Republic of 1921.The party was outlawed by the government of Reza Shah in 1931.

Читать дальше