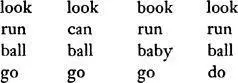

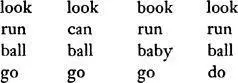

Find the word that is different in each row.

Along with the reading exercises came the printing exercises. Edwin, who had learned to copy the capital letters of his name shortly after the age of four, was nevertheless entranced. He liked to connect the dotted outlines of the letters, as earlier he had connected the dots in innumerable coloring books, and he liked to practice printing his name in a dotted version:

Later he was fascinated by the yellow paper with its alternately dark blue and light blue lines. He practiced his letters with passion and soon had a distinct feeling for each one. He had a special fondness for letters like  and

and  that rose over letters like

that rose over letters like  and

and  to touch the dark blue line above, and letters like

to touch the dark blue line above, and letters like  and

and  that plunged below the dark blue base-line to touch the pale blue line below. He was puzzled by

that plunged below the dark blue base-line to touch the pale blue line below. He was puzzled by  , which rose above the light blue line but was not permitted to reach the dark blue line, and fascinated by

, which rose above the light blue line but was not permitted to reach the dark blue line, and fascinated by  and

and  , with their dreamlike dots. He liked to form categories on the basis of similarity of shape: thus

, with their dreamlike dots. He liked to form categories on the basis of similarity of shape: thus  and

and  were related to one another in much the same way as

were related to one another in much the same way as  and

and  , except that the tails of the latter both began on the same side of the

, except that the tails of the latter both began on the same side of the  ;

;  was two

was two  ’s and

’s and  was two

was two  ’s; capital

’s; capital  was capital

was capital  with something added. The relation of capital to small letters intrigued Edwin:

with something added. The relation of capital to small letters intrigued Edwin:  was a bigger

was a bigger  ,

,  was a bigger

was a bigger  ,

,  was a bigger

was a bigger  , but what was the relation of

, but what was the relation of  to

to  ? of

? of  to

to  ? of

? of  to

to  ? of

? of  to

to  ?

?  and

and  were clearly related to one another but

were clearly related to one another but  and

and  were clearly not:

were clearly not:  was related to

was related to  , the only other small letter with a cross-stroke, and

, the only other small letter with a cross-stroke, and  to

to  . Edwin was always asking Mrs. Brockaway to explain these things, as if she had invented the alphabet, and Mrs. Brockaway was always telling Edwin not to ask so many questions, as if indeed she had invented the alphabet but refused to divulge its secrets. The early printing exercises impressed upon everyone, but especially upon Edwin, a sense of the physicality of letters — a sense that, the reader will recall, he first experienced in the alphabet books of his third year.

. Edwin was always asking Mrs. Brockaway to explain these things, as if she had invented the alphabet, and Mrs. Brockaway was always telling Edwin not to ask so many questions, as if indeed she had invented the alphabet but refused to divulge its secrets. The early printing exercises impressed upon everyone, but especially upon Edwin, a sense of the physicality of letters — a sense that, the reader will recall, he first experienced in the alphabet books of his third year.

The first grade was so much a matter of reading and printing that it would be misleading to do more than mention our other activities. Science meant bringing in leaves and stones; Art meant decorating our pencil-cans and learning how to mix powder-paints; Music meant shouting some preposterous song. Arithmetic was at first almost as interesting to Edwin as reading, for the numerals too had personalities, but the numbers formed from numerals were disappointing compared to the words formed from letters, and the games played with numbers, though they amused him, failed to arouse in him a lasting excitement. Only once did numbers truly move him: one day he learned the secret of rounding 100 and beginning all over again, a secret that seemed to open up vast spaces in his mind. But soon it seemed merely a clever trick, like the story Billy Duda later told in the fourth grade: “Ten boy scouts were sitting around a fire and each boy scout had to tell a story. The first boy scout said: ‘Ten boy scouts were sitting around a fire and each boy scout had to tell a story. The first boy scout said: “Ten boy scouts were sitting around a fire …” ’ ”—at which point Mrs. Czernik told him to sit down.

One first-grade subject unconnected with words does call for special mention, for it was the cause of Edwin’s first punishment at school. Most of the time Health was a half hour of ingenious tedium, but one day toward Christmas Mrs. Brockaway announced that Mrs. Hotchkiss, the school nurse, was going to pay us a visit. We were to keep our mouths shut and she meant shut. The door opened, and Mrs. Hotchkiss came striding in, wearing a white cap, a white dress with white buttons, white stockings, and white shoes. Under one arm she carried a large white piece of cardboard and in one hand she carried a long thin black cloth case approximately the size of a cheerleader’s baton. At Mrs. Brockaway’s desk she put down the long black case and proceeded to unfold two wings from the back of the cardboard, as if she were creating an angel. She then stood the piece of cardboard on the desk, facing us. The cardboard showed the vast black outline of a tooth. Edwin and Donna Riccio, who usually sat with their backs to the desk, but had turned their chairs around for this special occasion, both stared up at the huge tooth. It was Donna Riccio who gave the first quiet giggle; I could tell by the tenseness of Edwin’s neck that he was desperately restraining a convulsion. And I think he would have been successful had not Mrs. Hotchkiss picked up the long black case and proceeded to remove from it, slowly and carefully, the largest toothbrush I have ever seen. The bristles were nearly two inches high; on the other end was a red rubber point the size of a Hershey’s Kiss. It was too much for Edwin; he exploded helplessly, setting off Donna Riccio and Trudy Cassidy and the rest of the class; yet even then it was not too late, for although Mrs. Brockaway resembled a dragon, Mrs. Hotchkiss sweetly smiled. But as the laughter died down she became quite serious; and frowning over her pink-rimmed eyeglasses she began to explain the correct method of brushing one’s teeth. Edwin was in agony, he was a rigid knotted muscle of attention, he reminded me of the tightly knotted rubber band on the bottom of a tightly wound balsawood airplane; but again I think he would have been successful had not Mrs. Hotchkiss raised the monstrous toothbrush to the monstrous tooth and quite solemnly, without a smile, begun to brush. It was not the sight so much as the sound that finished him: at the first gentle brshhhhhh he let out a helpless howl. Things happened very quickly then: Mrs. Brockaway stormed over, grabbed his collar, and yanked him out of his seat; Edwin’s face filled with horror; and in a state of pallid shock he was half-dragged to the coatroom, where he remained for the rest of Mrs. Hotchkiss’s lecture, which proceeded without incident. Afterward, when he was let out, Edwin kept his eyes lowered and buried himself in his work; his eyes were red. Poor Edwin. He could no more understand other people’s solemnities than he could their jokes.

Читать дальше

and

and  that rose over letters like

that rose over letters like  and

and  to touch the dark blue line above, and letters like

to touch the dark blue line above, and letters like  and

and  that plunged below the dark blue base-line to touch the pale blue line below. He was puzzled by

that plunged below the dark blue base-line to touch the pale blue line below. He was puzzled by  , which rose above the light blue line but was not permitted to reach the dark blue line, and fascinated by

, which rose above the light blue line but was not permitted to reach the dark blue line, and fascinated by  and

and  , with their dreamlike dots. He liked to form categories on the basis of similarity of shape: thus

, with their dreamlike dots. He liked to form categories on the basis of similarity of shape: thus  were related to one another in much the same way as

were related to one another in much the same way as  and

and  was two

was two  ’s and

’s and  was two

was two  ’s; capital

’s; capital  was capital

was capital  with something added. The relation of capital to small letters intrigued Edwin:

with something added. The relation of capital to small letters intrigued Edwin:  ,

,  was a bigger

was a bigger  ,

,  was a bigger

was a bigger  , but what was the relation of

, but what was the relation of  to

to  to

to  to

to  and

and  and

and