One day she caught me watching her eat a packet of crisps, licking salt off her fingers, and she blew me a kiss across the canteen as if she thought I fancied her. She could be daft and funny that way. Then we ended up sitting together in class. It was engineered under the impatience of our history teacher, who got fed up with Manda’s constant giggling and barracking alongside goggle-eyed Stacey Clark on the back row. There was a space by me, with Rebecca Wilson being off poorly, and Manda got shifted.

Would you sit there and behave, please, Amanda, Ms Thompson instructed her, three times, each one louder and a little more desperate.

After tutting in the mardy fashion of a criminal playing victim, she screeched her chair out from under the desk and stalked over to my table. I got to see her up close for the first time, and her eyes were what my grandad would have called ower glisky — bright after the rain. She looked long at me. I knew it could go either way between us then. When you pen two animals in at short quarters they’ll either take to each other and settle into company or they’ll set to, gnashing and bucking.

Manda leaned over, clutching her pen tight and far down its stem, like a little kiddie would hold it, and she drew an inky scribble on the open page of my exercise book. So I put a scrawl back on hers. I did it without pausing — tit for tat. I saw she had a little heart carved into her wrist from a compass point, a thing which only the halest girls did. The scratch bloomed yellow-red, like a septic rose against her skin. Halfway through the lesson her biro ran out and she selected another from my pencil case without asking. She put it back when she was done.

Something was granted to us afterwards. We were past simply knowing the name of the other and what form we were in. We were allowed to say Hiya in passing, in front of our other friends, at the gates of the school, or in Castletown going down to the chippy or the arcade. Not that Manda needed permission for her friendships. She spoke to all manner of folk that were ordinarily off limits to the rest of us: the older, knotty-armed working lads who drove spoilered cars through town on their lunch breaks and knew her brothers to drink with; the owner and dealers of Toppers nightclub, and the tall, tanned girls who served at the bar there and trod that fine line between being queens and sluts with their reputations for giving good sex, bent over counters after closing time. Inside the old Covered Market, Manda spoke cheekily to the sheepskin-jacketed gents from Carlisle racecourse, as if they were her uncles, and they might have been her uncles.

And there was her mam’s lot, the foreign cousins who came to the driving trials from Ireland, Scotland or Man, and brought with them piebald cobs, fiddles, rumours about filched electronics, litter and unfettled debts. The town banged on and on about their arrival each year, half of it discrimination, half superstition from a century before. How they were rainmakers and crop-ruiners. How they had curses or the Evil Eye. How they crossed the Border at night to the peal of the Bowness bells, said to ring out from their wath grave in the Solway when robbers were around, blah blah. Manda stepped into their loud circles and blagged cigarettes and gossiped and got invited to their hakes. She put up with nobody saying within earshot they were dirty potters and pikes.

No grand treaty was needed for her to know me. There came a day when I walked with her and a small crowd downtown for a gravy butty at dinnertime. I was standing near them in the cloakroom waiting for Rebecca to meet me, all of us putting on our coats and ratching in our purses for coins. Her face was dark inside the lum-pool of her hood, and she said, Come along on with us if you like, Kathleen.

What have you asked her for? one of the others rasped.

Because I’m fed up with your ugly mugs, Manda replied.

She and I walked together with linked arms from the Agricultural Hotel to the bottom of Little Dockray. Who isn’t looking at us, I thought, and my heart was going at two-time.

The next month I was one room away while she got laid by a friend of the family — a jockey, who was married with kids. She reported back that he had a prick the size of Scafell and his come had run down her leg. Six weeks after that I sat with her in the clinic while she took two pills for her abortion, and I held her shoulders while she was sick. She said the nurse had told her not to look when she went to the toilet, but she had looked down into the bucket by her feet. It wasn’t like period clots, just a ball of tubes. She said no bloody way was her mam ever to hear of it because her mam would’ve wanted the babby kept.

High Setterah was not the house of a rag-and-bone family. The grime of cart-claimed money had been swept back a generation by the Slessors branching out into carpets, property, equestrian prowess. Their travellers’ heritage was easily remembered in a town which never forgot former status, but they’d grafted a fortune which made them untouchable by recession, competition, the bitter regional snobbery. The building was low and sprawling. It was almost a mansion except that it looked more like a Yankee ranch, with wooden interiors and a veranda. It had no business being built in Cumbria, one spit off the National Park boundary, and must have been forced past the council planners in the late seventies when the family was in its ascendancy, for it duffed all the local planning laws. There were paddocks front and back of the house for the horses, and slated stables off one wing of the property. Occasionally you could smell the beefy stench of Wildriggs abattoir wafting over from the industrial estate.

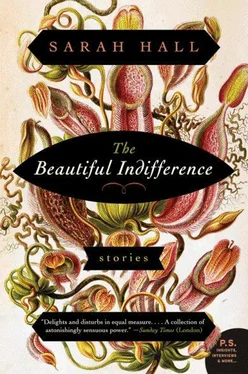

Inside there were too many bathrooms to count — the beautiful indifference I was always scared I’d go in a wrong door — and pungent utility rooms where the Dobermann and the mastiff were kept. There was a sauna and a games room. Everywhere were hung ornately framed pictures of champion breeds, red ribbons indicating the annual royal downfall in the territory, brass reminders of the family sport. There was a long drive up to the house from the Kemplay roundabout and all alongside it were those glistening, hardy ponies, made stout by the gradient of fells, made tame at the Wall by the Romans, and now made fast by the leading reins of the Slessors.

Everybody thought it was Manda’s dad who was the horse expert. And with his mule-neck and muscles straining as he bullied them across the beck at Appleby fair, they had no reason not to think it. Geordie was a master of saddlery. He wasn’t well respected by the rest of the nation’s breeders, the manor-house owners and Range Rover drivers, and that ritted him deeply. But they still came to him for advice and opinion on their steeds; they still bought his stock. He was always interviewed by the regional news stations after the trophies were won, his yellow Rolls-Royce parked prominently behind him. And though he had no right by birth or blood ever to own a car like that, he commanded the cameras in its direction, like it was the golden spoils of a chor shown off by a thief who knew cock to collar he would never get caught.

But it was Vivian Slessor I saw bringing stubborn geldings into the stables with brobs of fennel, in the old way of northern handlers. Her crop was seldom used when she rode. Though her racing and rutting knowledge was the lesser professionally, as a horse-handler she was somehow greater than Geordie — for her intimacy and charm, her hands working the tender spots behind the creatures’ ears to quieten them. Geordie looked to her as his official bonesetter when a horse was damaged, rather than ringing the vet and being billed. He stood back as she bound up a foreleg with sorrel. One windy, mizzling day in April, Vivian Slessor first got me up into the saddle — on a gorgeous chestnut mare too big and blustered for someone of my size and inexperience. She softly talked and tutted as she led us round the paddock in the gale, and I wasn’t sure if she was scolding the horse for cross-stepping or scolding me for bad posture. At the gap-stead of the field she unclipped the horse’s rein.

Читать дальше