I dry slowly in the dying embers of the sun, and as the water evaporates a slight chill wrinkles my skin. For some reason, I feel like I am being kept here on the sandbank by some spirit’s still unfulfilled wish. It is a stupid superstition but something I feel strongly nonetheless, despite the fact that there has been no proof of it. An egret lands nearby and studies me with curious eyes. I feel a breeze across the river’s face and look up. A canoe drifts slowly past, a skeleton piloting it. I shiver, suppressing an urge to scream. Sometimes my childishness still plagues me.

The canoe becomes entangled in some lilies growing in a green and white cluster, and though the tides are pulling at it, I know because the lilies are nodding their white heads in time that the boat will not dislodge. The skeleton sways back and forth with the boat’s motion and it makes me think of an elaborate decoration on a Swiss clock. There is a cobweb between the bony arm and the empty chest. It is beautiful and shimmers in the fading light. I wonder how long this poor soul has been lost, even as I admire the cobweb, thinking it reminds me of another time. Of the doilies and small caps I used to crochet all those years ago.

I reach out my hand and try to touch the spider’s web. It is perfect. But I can’t reach it. Just as well , I think, catching myself. For all I know, this could be a booby trap. The enemy knows our reverence for death and its ritual and could have just sent this downriver intentionally. I examine the bones. There is no way to know what he, or she, died of. Standing up, I back away from the boat and gather some pebbles of varying size and weight and then lob them at the canoe. If it were booby-trapped, this would set off any bombs. Satisfied that it is clean, I walk over to one of the huts and pull a long pole from its roof, and with great difficulty I maneuver the canoe aground.

Leaving it for a while, I dig a shallow grave in the shifting sand, knowing it will be washed away in next year’s flood. But that is unimportant. What is important is that this person be buried. Be mourned. Be remembered. Even for a minute. Before I take the skeleton out of the canoe, I reach in and pull the cobweb gently free. I drape it over my head like a cap and then lift the skeleton with ease, careful not to shake any bones loose. To come back complete, it is important that one leave complete. Laying it in the grave, I cover it hurriedly and say a soft prayer and play “Taps” on my harmonica. It is the least I can do.

There are so many restless spirits here. Maybe this is why I am dallying here, delayed by the need of this lonely spirit to find rest. Tomorrow I will leave with the salvaged canoe. That is the way here. I feel the grateful blessing of the spirit in the wind on my cheek.

“Farewell, friend,” I whisper.

Truth Is Forefinger to Tongue Raised Skyward

Every star is a soul, every soul is a destiny meant to be lived out. They fill the night sky, revealing like a diviner’s spread the destiny of those gifted in reading their drift, their endless shift, like a desert, revealing and burying the way alternately.

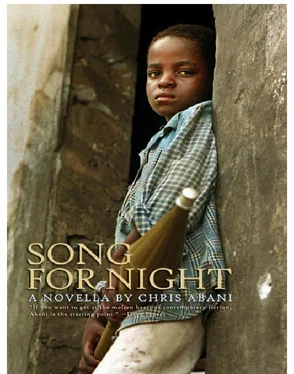

I have killed many people during the last three years. Half of those were innocent, half of those were unarmed— and some of those killings have been a pleasure. But even with all this, even with the knowledge that there are some sins too big for even God to forgive, every night my sky is still full of stars; a wonderful song for night.

I sigh and lean back in the canoe. The current has changed direction and is flowing upriver now; inland. The corpses, like a reluctant company of dancers, bump into each other as they hit the sudden swerve of the water, bump into each other and waltz lazily back the way they came. The corpses seem to be mocking me. They seem to say, Don’t worry, you’ll be one of us soon, you’ll join us in this slow dance.

My Luck is dead.

This is what my mother would say if I die in this war. I say would because she is already dead; but that is another matter. My Luck: that’s what she named me, fourth son after three daughters, all of whom died of mysterious sicknesses before they were eight. In this culture, a woman who bears only daughters is not worth much to her husband and family: maybe not worth anything. In my family, the women lose a lot of babies. Like Aunt Gladys. I remember the night she came round to our house all bruised up from a beating from her husband. I was only five but I remember it. We were all sitting by the fire outside roasting corn and pears, my father, my mother, and I.

They talked in muted whispers, my parents and her, in the low glow from the fire, with the shadows riding close by; they looked haunted. Though they were whispering, I could make out that she had somehow lost her baby, and I thought it was careless of Aunt Gladys to lose her baby like that. I mean how can it be in your stomach one minute then lost the next, sailing down a river of red. The last part I had just heard: Aunt Gladys saying it was like a river of red, the blood that gushed from her. It made me think of the chicken we had killed for our Sunday dinner that still had unlaid eggs in her. My father took the eggs out, his eyes sad. I poked them, surprised to find that they were soft like snake eggs, and my stick pierced the soft case of one and the egg burst, revealing a spit of blood and mashed bones and feathers. Father covered it in sand and muttered under his breath.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

“Praying. You should too.”

But I didn’t. I still haven’t: not for any of the lives I have taken. Or the ones I have lost. But it was hard to imagine Aunt Gladys’s river of red having small crushed bones and feathers. Does her husband pray even now for the life he took? I was very quiet, even then I said very little. I should have been asleep and it was a rare privilege to be allowed to sit with the grown-ups, so I wasn’t about to mess that up by talking. I looked up from the ground and studied Aunt Gladys crying there and risking everything, then I stood up and came over and curled myself into the small of her back, my tiny arms around her belly. I’ll never forget the sigh she let out. It was like she had taken the last breath of air on the planet but had to let it go.

“My Luck,” she said. “My Luck, do you know what lonely feels like?”

I didn’t know. To my five-year-old mind it might have been like losing my puppy or the dirty secondhand teddy I loved so much.

“No, Aunty,” I said.

“Lonely is a cold, itchy back,” she said.

I laughed and snuggled closer, one hand scratching her back through her thin blouse. She sighed happily and my parents laughed. I keep that night close, like a well-worn photograph of family, of a time when we were happy. My father died shortly after that night, and my uncle, my father’s half-brother, became my father and my mother became his mistress, and I the burden that stared at him daily with a malevolence he couldn’t beat out of me.

I stretch and lean further back and stare into night, the wood of the canoe hard against my back like a hand. A little fire burns in the leaking metal pail I found on the sandbank. I filled it with hot coals and kindling and set it in a wet block of wood in the center of the canoe; the way I had seen Grandfather do so many times. It would keep me warm this cold night, and the light, too faint to be seen from the bank, was enough to comfort me in that river of the dead. Fire and starlight and the wood of the boat; and something else — hope that I will find home in the morning. Thinking of Aunt Gladys, I know now of course that she was right. The heart is not where we feel loneliness. It is in the back. I press mine harder against the wood behind me, but it is cold and wet from the river. With drooping eyes I watch the fire die.

Читать дальше