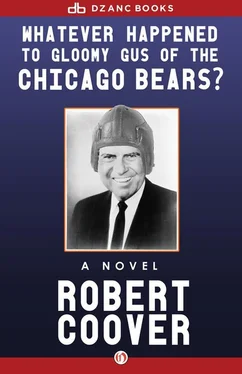

Robert Coover - Whatever Happened to Gloomy Gus of the Chicago Bears?

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Coover - Whatever Happened to Gloomy Gus of the Chicago Bears?» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Издательство: Dzanc Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Whatever Happened to Gloomy Gus of the Chicago Bears?

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dzanc Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Whatever Happened to Gloomy Gus of the Chicago Bears?: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Whatever Happened to Gloomy Gus of the Chicago Bears?»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Whatever Happened to Gloomy Gus of the Chicago Bears? — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Whatever Happened to Gloomy Gus of the Chicago Bears?», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She described it all, phrase by phrase, gesture by gesture, touch by touch — I found myself getting excited in spite of myself — and exactly what happened to her each step of the way. “There’s no grabbing, no fumbling, his hands slide from my face to inside my underwear like magic, Meyer, like water running over pebbles in a brook, you know? Gemitlech-like, going from some place to another place, sure, but remembered like being everywhere at once, and he is whispering in my ear and kissing the insides of my legs and smiling down at me from above, and I don’t know where I am anymore! ‘Surrender to the ancient force inside you, Golda,’ he says, ‘struggle against death!’ Is he kidding? The surrender is over, he’s— zetz! — inside me already, he’s— ah! — my clothes are gone but— oi! — filling me…!” The last part got rather blurred, but by then the words weren’t very important anyway.

She lay on my cot after, her clothes sweaty and rumpled, her hand between her thighs, her face suddenly aged and filled with so much sorrow I lost all my own excitement and wished only to hold her like a child and give her comfort. “Meyer,” she whispered, “would you do me a favor?”

“Sure, Golda…”

“Watch him, Meyer. Watch what he does to me.”

“You mean while he—? Well, I don’t know, Golda, I don’t much like—”

“Please, Meyer. For me. He’ll come here tomorrow. Keep the others away and watch. Tell me what happens, the whole megillah, tell me if I’m crazy or what.”

As usual, spineless as ever, I could not say no. The next day was Friday and Gus turned up as expected. I’d chased the others off, telling them my aunt was coming to visit. (And what would have happened, I was to wonder later on, when it was all clear to me, if Gus had taken my crazy aunt on?) I didn’t even have time to hide, but Gus didn’t seem to register my presence, and Golda after the first minute or two was conscious of nothing except Gus. And it was all true, the whole transaction, word for word, move by move. Gus entered the studio, walked to the back to get fed, noticing nothing en route, and there she was. She looked frightened and painfully self-conscious, yet approachable as a park bench; he seemed as insentient as ever, staring at her like she was the horizon. But then suddenly there was that flicker of recognition, the little gestures, and Golda, like Pavlov’s dog, began to respond. “Golda!” he said gently. “Golda, I’ve been looking for you!” He took her hand.

It was very smooth, very professional, yet sincere and intense at the same time. He went through the entire routine, just as Golda had recounted it, but though I’d heard it all before and stood objectively apart, trying vainly to apply Freud to what I saw, it was such an absorbing spectacle it all seemed like new. I tried to watch his hands, but I, too, got caught up in the timelessness of his performance and could not remember afterwards exactly how he undressed her. “Oh, Dick!” she groaned (she was the only one of us who ever used his real name). “Take me! Love me! Save me!” I left before the climax (he was technologically up-to-date, I’d noticed, using one of those slide fasteners on his fly instead of buttons), having seen that part before, went outside and planted some flowers in the vacant lot next to my studio, thinking: It is true that love is a momentary denial of reality and death — but then, is that its true and secret function: to serve as a defense mechanism against other forms of madness? I realized I was very agitated and falling back on defense mechanisms of my own.

After Gus had fed himself on my food and left, I went back in and found Golda sitting on my cot, dazed, a bit desolate, but not unhappy. She was dressed but not tucked in, and held in her hands, which were shaking slightly, what I thought at first was a handkerchief, but what I then recognized as her underpants. She looked soft, fat, somnolent, but, as always after one of these episodes, years younger than her age. “Well, Meyer?” she whispered. “Am I crazy? Did you see?”

“I saw, Golda. It’s like you said. The whole thing. It’s very strange… every time, just like that?”

She smiled wearily, stood and pulled her underwear on. “Sometimes he doesn’t call me Golda,” she said sadly, gazing off through the walls of my studio. She smoothed her skirt down, tucked her blouse in; it was the kind of costume little girls wore to the country on weekend outings, though it was still winter in Chicago.

But then a few days later she staggered into my studio all bruised up, her eyes blackened, a tooth missing in front and her jaw swollen. As soon as she saw me, she started to cry. I scrambled down the ladder. I thought she might have been hit by a car.

“It was Dick,” she wailed stiffly through her swollen jaw. “He hit me…!”

“My God, Golda!”

She fell forward on my shoulder and I started to embrace her, but she winced and pulled back: “Oh! I hurt all over!” she bawled.

I led her gently to the back, turned on the hot plate to heat up coffee. “How… how did it happen, Golda?” I asked. I was very upset and nearly tipped over the coffeepot, while setting it on the burner.

“He tried to kill me! He stole my purse!”

“Why? Why did he do such a thing?”

“I don’t know, I don’t know what’s happened!” she sobbed. “Oh, God help me, Meyer, I think he’s ruptured something inside me!”

“But did you say something? Did you do anything to make him—?”

She wiped her eyes on her sleeve and looked up at me. There was such a depth of sadness in her eyes, such a terrible mix of despair and longing, that I thought I was going to cry myself to see them. I’d put a box of cookies on the table, and absently she picked one up and bit into it — she gave a little yelp of pain and clutched her mouth as though trying to keep the teeth that remained from falling out. “All I did,” she mumbled through her fingers, “was ask him why it was always the same.”

“And just for that he—?”

“I went to see him at the theater. He starts up when he sees me, just like always. I stop him. I says, ‘Tell me what you really think of me, Dick. I’m not a child,’ I says, ‘you don’t have to lie to me, I’m nearly twenty-nine’—forgive me, Meyer, I just couldn’t…”

“But you think that’s why he hit you? Just because you lied about your age—?”

“I don’t know, I don’t know. All I’m sure is the minute I said ‘twenty-nine,’ something very peculiar come over him. Suddenly, he stops staring at me like he’s Valentino and starts looking more like Wolfman — Meyer, I can’t tell you, it was awful! Geferlech! He ducks his head between his shoulders and he squats down like he’s got cramps or something, holding himself up with one hand, but balling the other one up like he’s gonna hit somebody.…”

“Oh no!” I remembered that night I’d met him, the whirr- click! as I’d switched cues on him; we’d tested him a few times since and it was always the same. “So that’s what…!”

“Yes, he’s snarling and grunting and showing his teeth like some kinda mad dog or something, quivering all over. I was scared. He rears his tokus up. I says, ‘Wait a minute, Dick, we can talk about this—’ And— plats! — he hits me! He just bucks forward, smacks into my belly and klops me clean through a wall in the set, off the stage, and into the orchestra!”

“My God, Golda!”

“My purse flies outa my hands. He grabs it in midair, hides it in his elbow, hunches his head down and shlepps it right outa the theater! Oh, Meyer! I just wanna die!”

I looked into her eyes. The flesh around them was puffy and discolored, but that would go away. She’s seen a lot, I thought. Maybe almost enough. “Golda, would you model for me?”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Whatever Happened to Gloomy Gus of the Chicago Bears?»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Whatever Happened to Gloomy Gus of the Chicago Bears?» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Whatever Happened to Gloomy Gus of the Chicago Bears?» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.