He looked at the other one. His face was crooked. He looked the younger of the two, maybe. He smiled as well. It was all very civilized.

— Or, said this one, his crooked face falling straight when he talked. You could take my phone number. You could go back home and have a nice relaxed Sunday night and enjoy the rest of your week, and you could keep doing the driving, and whatever else comes up, for Mr Mishazzo. And let us know. Nothing dramatic. Just where you take him, who he meets, what he says on the phone, that kind of thing. We’re not asking you to do anything. Just listen. And be your own man. Able to walk away from him and from us any time you like. Safe. You stop the hotels. But apart from that, nothing. You just have a couple of new friends.

They let him think about it. They never mentioned her once.

He went home and cooked for her and she sang bits of things at him and laughed at her own voice. They lay together in front of the television for a while and then she wanted him to tie her up, to practise his knots, to fuck her, come on her, fuck her again.

Mishazzo said to him:

— When you turn to the right you have a tendency to cut the corner. To slice it. Ever so slightly. When you turn left it’s not a problem. You are leaning to the right. Do you have a limp?

— No.

— You’re right-handed?

— Yes.

— Your legs are the same length?

— Yes.

— And your arms?

— Yes, I think so.

— You get your eyes tested?

— My eyes are fine.

— One isn’t weaker than the other?

— No. My eyesight is … you know. Twenty twenty.

Mishazzo looked around the backseat.

— Do you dress to the right?

He laughed.

— I think it goes down the left side actually. You know. If anywhere.

In the mirror Mishazzo nodded.

— Well, that explains it then.

She worked a couple of days a week in a café in Stoke Newington. Serving, and some cooking too. Frying eggs and bacon, making sandwiches. She didn’t like it when he came in. But he came in anyway, sometimes, when he was nearby.

— Let’s go on a holiday, he said.

— Where?

— Anywhere.

She thought about it.

— Spain, she said.

— You’ve been to Spain.

— I liked it.

— You don’t want to go somewhere new?

She wrapped an arm around his hip.

— I didn’t see everything they have there.

— We could go to France. Or Morocco. Derek went to Morocco, said it was great.

— We could go to Spain and then get the boat to Morocco.

— How long does that take?

— It’s really close. Really short.

— Is it?

— Yeah. If you look at it on a map. It’s where Spain and Africa nearly touch.

At home, she went online and found a map. They looked up ferries and prices. He wondered whether they could live in Morocco. They could probably live more easily in Spain. He wondered what they could do. He could learn Spanish.

He thought that Mishazzo probably had lots of friends in Spain.

— So then now. What are you interested in?

— Sir?

Mishazzo was sitting on the back seat with his legs crossed, smoking a cigarette, looking at him in the rear-view mirror.

— Is it money? Are you interested in money?

— Yes, I am.

— Well of course. You think I pay you well?

— Yes sir.

Mishazzo was smiling. He had come out of a meeting in a Golders Green café, all smiles. Now they were stuck in traffic on the Hampstead Heath back road.

— You have a girl?

He blushed. It was the first time Mishazzo had asked. He had a plan. He had the whole thing worked out and ready. But still he blushed.

— A boy?

— No. I have a girlfriend.

— It’s a serious thing? A love thing?

— No, not really. We get on well. But it’s … it’s not very serious.

— You live with her?

— We share, yes. It’s more convenient that way. Financially. Makes sense.

— You love her?

— It’s more like a friendship.

— You love your friends though.

— I suppose. But it’s a different sort of love.

He nodded in the mirror, his face behind smoke.

They sat still for a while. Mishazzo rarely liked the radio. Sometimes he requested a CD. He liked world music. African. Middle Eastern. He would tap his hand on his knee, or bounce his leg up or down. He liked joyful music.

— I’ll see. Maybe you can do more driving. And maybe some other things too. You are very young, and you have no face. So. More money for you. And your girlfriend.

When they got into Highgate Mishazzo told him to pull in to the side of the road and to turn around and look at him.

— You should be careful who you make your friend. And who you take into your bed. They are different things. If you mix them up you lose … perspective on both of them. Do not mix them up. That is my advice to you, my friend. The dick has no loyalty. Only the heart. But your head manages them both. So be clever. Be happy. Have fun. Have money. Have beautiful girls. Have a good life. Do not fuck your friends. Only your lovers. Never fuck your friends.

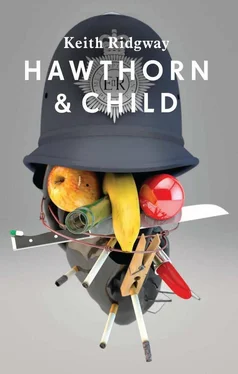

He met Hawthorn in some coffee shop on Stroud Green Road, full of people with laptops. He looked at screens and bags and people’s faces. He didn’t know if they were students or what. They took a table outside. It was hot. Hawthorn was wearing a T-shirt and jeans. He was less like a cop. But his leg jigged up and down all the time and his hair was cut.

— Are you off duty?

— Not really.

Hawthorn asked him where he’d been on Thursday and Friday. He got him to go through the times, the route he’d taken. How many phone calls had Mishazzo made? What had he said? What names did he use? Had he opened his briefcase? What was in it? What sort of mood was Mishazzo in? He bought the coffees. After he’d asked his questions and written some stuff down in his notebook he sat back in his chair and smiled.

— Now I’m off duty.

The way he’d said it, it sounded like a sort of come-on. They looked at each other. Hawthorn half blushed, up near the tops of his cheeks, like some invisible thing had just flicked fingernails against his face. He looked away.

Nothing happened for a while. Then Hawthorn looked back at him. Held his eyes. For exactly the amount of time it takes for a look like that to become a look like that.

They met sometimes in the coffee shop on Stroud Green Road, sometimes in a pub in Holloway. Or near Hawthorn’s flat, so that they could go there, if they wanted to. Sometimes he met Child as well, and then they usually just sat in Child’s car, or they drove around. Hawthorn wrote in his notebook. He got the feeling that they knew everything already. That he was just confirming stuff. Maybe they were testing him. He made a few things up. He told them about a route he hadn’t taken. Said they’d gone out to Hackney when they hadn’t. Nothing seemed to surprise them. He didn’t understand why any of it was important — the roads and the times — unless they were trying to trip him up. He knew the names were important. The phone calls, the buildings and houses and cafés he waited outside. The bits of conversations.

He thought that it was all probably bullshit. That he wasn’t telling them anything they needed to know. They would spend six months getting him used to them, and then they would start to press. See if you can find out this or that. Or maybe they were waiting for Mishazzo to begin to trust him more.

He didn’t tell them about the bottle. About sitting there dying for a piss, sure that as soon as he started, Mishazzo would reappear. He didn’t tell them about smoking more than he’d ever smoked before, out of boredom. He didn’t tell them about trying to think of things to write in the book, or how most of the things he thought of were things he would never write. His mind was dividing. Parts of it were roped off. There were things he could say. There were things he could not say but could write in the book. And now there were things he could neither say nor write but only think, and they pressed up against the others like they wanted a fight.

Читать дальше