Oh, I dunno, said the journalist despondently. Let me think about it.

He sat there and the waiter came back and he said: Tiger beer.

He took one sip that he didn't want and said: Tell her it's OK. Tell her she doesn't have to come. Tell her I'll say goodbye.

Eyes bulging, the English teacher repeated this information in a voice of machine-gun command. Or maybe he said something entirely different. That was the beauty of it.

She said something to the English teacher, who said: She is very happy to have meeting you.

Well, the journalist thought or tried to think, that's it. Really it's just as well. .

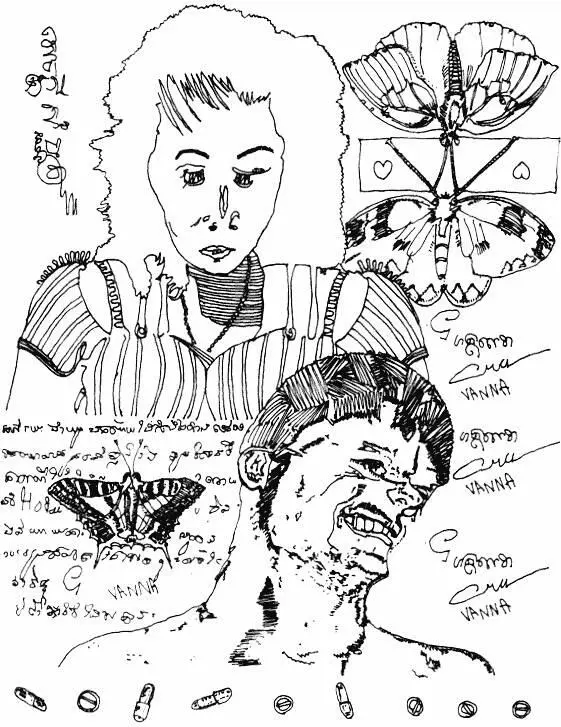

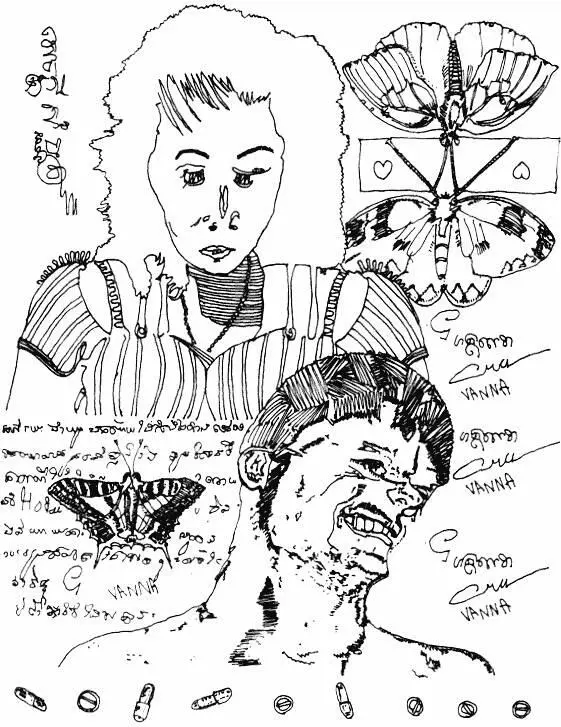

… as Vanna came to him and gave him something wrapped up neatly in a square of paper, and again he had a sinking feeling, believing that she was returning his letter, and it seemed right and fair but also very sad, and then because she was still standing there he opened it to learn that it was something very different, lines of Khmer written very neatly (possibly professionally) with loops, wide hooks, spirals, heart-shaped squiggles, everything rounded and complicated, flowing on indecipherably.

The English teacher said: She go to get free from customer.

OK, he said -

He was happy and amazed. He sat there and the English teacher sat with him.

She came back and said something to the English teacher, who said: She will go home now to dress. Please wait for her. She return in twenty minutes. She come for you.

She comes for me at the hotel?

Yes, said the English teacher.

He took the English teacher outside and sat him down in the light outside an apartment building. He asked him to translate. The English teacher looked at the letter for a long time. Then he said: I will tell you only the highlights. .

Please tell me everything. Can you write for me everything? Then I go to the hotel to wait for her.

The English teacher wrote: Dear my friend.

She comes for me at the hotel?

Yes.

The English teacher wrote: It's for a long time wich you went to Bat dorn Bang provinc by keep me alone. I miss you very much and I worry to you.

She comes for me at the hotel?

The hotel? said the English teacher in surprise. No. She — she arrive for you at disco. .

He rushed back across the street while the English teacher sat translating. The doorway to the disco was very crowded. As he tried to enter, a man stuck out a leg, and he clambered over it. Another man pressed a glowing cigarette against the thigh of his pants. He pushed the hand and cigarette away, and brushed off the sparks, which were already half quelled by sweat. The photographer and his girl were still there, drinking Tiger beers at the same hot sticky table, while the music pounded indistinctly through the dripping air that stank of ghosts and sweat and lust and fear and unhappiness.

Has she come back? he said.

No, said the photographer. The photographer's girl looked at him owlishly from under the photographer's arm.

Tell her I'll be waiting right across the street, he said.

The English teacher had translated: I think that maybe you was abandoned from Kambodia & not told me.

Why can you write so much better than you can speak?

Yes, the English teacher said.

91

She wouldn't ride in front of him on the motorbike anymore. She made them ride separately and pay both drivers. Had people been torturing her too much, or was she just lazy? His driver paralleled hers, so that all the way back to the hotel he could watch her sit side-saddle on the bike, gripping some handle between her legs, her clown-pale face almost a toy, smiling like a happy mask.

He was desperate to know what her letter said. It was so hard not to be able to talk with her. He wondered if she'd had to pay someone to write the letter for her, or whether they'd done it for nothing.

He held her, and when the photographer came in and turned on the light, he saw that she'd fallen asleep smiling at him.

92

The letter said:

Dear my friend.

It's for a long limes wich you went lo Bai dorn Bang

provinc by keep me alone. I miss you very much and I

worry to you. I think that maybe you was abandoned

from Kambodia & not told me.

Since you were promiss to meet you at hotel I

couldn't went because Ican'l lislen your language. So

you forgive me please. In fact I was still to love you

and honestly with you for ever.

After day which I promissed with you I had hard

sickness, and I solt braslet wich you was bought for me.

So you forgive me.

When will you go your country. Will you come

here againt? And you must come Cambodia don't

forget I was still loves you for ever.

In final I wish you to meet the happiness and loves

me for ever, I wish you every happiness and loves me

for good.

Signature, love VANNA xxx

93

He sat rereading the letter under the rainy awning where the cyclo drivers sat drinking their tea from brown ceramic teapots with bird-shapes on them; they recounted their skinny stacks of riels as lovingly as he retold her words to himself; they rubbed their veined skinny brown legs; and he thought: Am I so far beyond them in soul and fortune that I can spend my time worrying about love, or am I just so far gone?

After a quarter-hour the rain stopped, and the cyclo drivers took the sheets of plastic off their cabs and dumped masses of water out of them. The proprietor of the café brought them their bills. The Khmer Rouge had put his family to work near Battambang. They'd beaten his wife and three children to death with steel bars because they couldn't work quickly enough. He had seen and heard their skulls crunch. They did it to them one by one, to make the terror and agony stretch out a little longer. They'd smashed in the baby's head first; then they deflowered his four-year-old daughter; then it was his seven-year-old son's turnto scream and smash like a pumpkin and spatter his parents with blood and bone. They saved the mother for last so that she could see her children die. The proprietor was a good worker; they had nothing against him. He knew that if he wept, though, they'd consider him a traitor. He had never wept after that. His owl-eyes were wide and crazy as he fluttered around the café exchanging bread and tea for money. He was like a mayfly in November. And the journalist thought: Given that any suffering I might have experienced is as nothing compared to his, does that mean I'm nothing compared to him? Is he greater than I in some very important way? — Yes. - So is there anything I can do for him or give him to demonstrate my recognition of the terrible greatness he's earned?

But the only thing that he could think of to help the man or make him happy was death, and the man had refused that.

Then he thought about giving the man money, and then he thought: Yes, but Vanna is as important as he is. And because she loves me and I love her, she is more important.

As for tragedies (which were a riel a dozen in Cambodia), what about the circular white scars on her brown back, put there forever by the Khmer Rouge when as a child she couldn't carry earth to the rice field dykes fast enough? If he could have gotten into his hands the people who'd done that to her, he would have killed them.

Читать дальше