The man couldn’t stop talking about it. He had to tell the story again. — They told us to vacate, he said. They held us up on trespassing charges. Couldn’t go back. They let us take some of our stuff, our blankets…

How were you feeling? Tyler asked, wanting to understand.

Empty inside. Angry, ’cause I didn’t understand why. We’re not harmin’ anyone; we’re not burglarizin’…

Tyler nodded, sitting there on the sidewalk.

I didn’t go to jail, said the black man, strangely desperate to continue his story. Went to an abandoned building on Ninth and Fourth. The city would come in and roust us out for a day on misdemeanor charges, then back we’d go. We called it the round robin.

All right, brothers, Tyler suddenly cried, filled with the same meaningless but searing urgency which had rushed him out of Coffee Camp and which sometimes drew him back to Coffee Camp, which had locked him into being the Queen’s slave and into loving Irene and hating Irene and fucking the false Irene and making love to Celeste, so what’s to live for?

Moneyman! they replied laughing, and Stanley explained: When Moneyman come around, he come in his station wagon. Everybody be here, he get a handout from Moneyman. Moneyman hand out the dollar bills like candy, then he go.

Tyler looked at him. — How’s the habit, Stanley?

When you set a time to stop, to stop smokin’ crack, to get up off the Slab, then you settin’ yourself up for a relapse. Recognize the Power that’s greater than you, Henry. Trust Him. That’s the only thing you can count on.

Tyler watched as he counted his quarters, stood up painfully, and went off to buy crack.

He awoke with the taste of Irene’s cunt in his mouth. I hate Irene! I hate Irene! I hate Irene! I hate Irene! I hate Irene! I hate Irene! I hate Irene!

I like the slow, nice, quiet life, Waldo had said. No adventures, no drama. It is the last spot on earth. — And he’d spread his hands, there in his underwear.

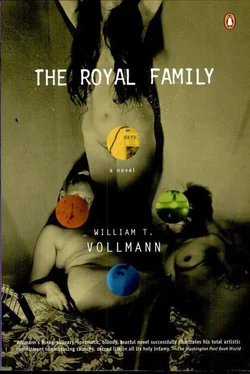

BOOK XXXVI. The Royal Family

And the Lord put a mark on Cain, lest any who came upon him should kill him.

GENESIS 4.15

Hal Lipset died, said Celia.

What’s that? John irritably returned, checking international exchange. The Thai baht, the Korean won and the Malaysian ringgit were still low. Already foreseeing the day months ahead when the Chronicle would read Stocks Lose 207 Points on Asian Jitters, he decided to devolatilize, which is to say coagulate, certain investments.

You know, that guy that bugged the martini olive.

Uh huh. And whatever Greenspan does is going to hurt. I can see that coming. Good thing your mutual fund is—

John, are you listening?

Oh, him, said John, bored. Back in 1965, right? Just a demo for the Senate. A life of twenty minutes and a range of twenty feet. I’m going to be home late tonight. Rapp’s at his wit’s end with that stupid Pannel file, so I have to clean up his mess—

How do you remember all that stuff? said Celia in astonishment.

What stuff? That’s my job. Some people have to work.

No, I mean like all that stuff about Lipset’s olive.

Mom brought me up well, I guess. Which reminds me. We need to shoot up to Sacramento to clean the headstone of Mom’s grave.

What about Irene’s grave?

What about it? Are you jealous?

Yes.

John laughed. Connoisseur of restaurants, he preferred to memorialize Irene not only with the occasional angry and fugitive visit to Forest Lawn, but also with a drive to Western Avenue for a long lunch at Cho Sun Galbi, which had been Irene’s favorite establishment when she still lived at home. The gleaming aluminum plates and equally gleaming fume-hoods in the middle of the plasticized granite tables gave him a sense of satisfaction. He missed Koreatown a little. It gave him a sense almost of gaiety to imagine bringing Irene’s successor, Celia, to Cho Sun Galbi where, admiring the mellow beer-colored shadow of his drinking glass, he’d offer her kimchee as red as blood, and allow her to help herself from small white porcelain bowls of bean sprouts, sugar-dried fish. Laughing, talking loud, he’d regain his pleasures. Irene with her suicide had poisoned this place; so be it. Celia would impart new associations. Afterwards, in some pleasant hotel room, he’d get to enjoy Celia’s white legs like chopsticks flashing in a bowl of red kimchee.

John?

What is it now, Ceel?

John, how come you don’t like people to know you’re smart?

Oh, for God’s sake. Just for once, can’t we leave me out of this? One goddamned time. That’s all I ask… Fidelity made me five hundred dollars last week, but I think I’m going to lose it. You need to get your financial shit together, too, kiddo. How many times do I need to keep telling you? My goddamned broker’s just sitting on his fat ass. I call him my broker because he’s making me broke. Ripping me off, driving me straight to the poorhouse…

John?

Yeah, I know my tie’s not straight. I’m sick of this tie anyway…

John, do you ever worry about your brother?

John slammed the newspaper down. — And just what does Hank have to do with anything?

I don’t know. I guess that bugged martini olive reminded me of him.

Look, said John. He’s my brother that I don’t talk about. Period. Okay?

Do you think he knows how to bug olives?

Now you’re trying to goad me, John said.

Maybe he’s got this whole apartment bugged and he’s listening to us right now.

Wouldn’t put it past him, John laughed. Except that he’s probably sleeping it off in some doorway. I can’t believe that piece of work is my blood relative.

John?

What? I’ve got to go.

John, I’m pregnant.

From me or from a bugged olive?

You know, John, I had a talk with Irene once. Before she died.

Well, when else would it have been? Unless you believe in ouijah boards.

And she told me you said the same thing to her. She said you never trusted her. But you were in the wrong, John. She was always faithful to you. And you really shouldn’t say such hurtful things—

Oh, balls, said John. Whose side are you on — mine or Irene’s? Well, congratulations. What’s it going to be, marriage or an abortion? Let me know, but not right now, because I have to go. Can you straighten this tie for me?

Did you just propose to me, John?

Whatever. All right, so you won’t straighten my tie. I’m going. Make sure you double-lock when you go to work…

Let’s get married, John.

All right already. Twist the knife! Do we have to go on and on about it? No, cinch up the knot. Is it still crooked right here? Oh, Jesus, I’m late. I’m really late. You and your bugged olives…

They honeymooned in Hawaii, and then on a blue-grey Sunday John wanted to fly to Las Vegas to wrap up some Feminine Circus business with Brady (who in prison would resemble some old grey tree shooting up like the skeleton of a fabled pike, leaning each year farther against empty air). In the stretch limo which Brady had sent, the tulip-shaped glasses gleamed like rubies behind the long long windows, and the crystal decanters in their mirror-backed cases wore gold. John grinned and laid his hand on the back of his wife’s wrist.

Celia was in the bathroom, having just begun her first marital quarrel, during which she’d sighed: I guess I’m just saying that I think there’s room for you to open your arms to more people than just yourself, and John, who’d heard it all before, was sitting on the bed removing his suits and her dresses from the garment bag when the phone rang. — What’s up? he said.

Читать дальше