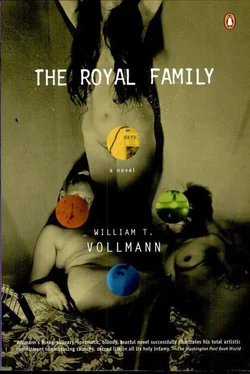

William Vollmann - The Royal Family

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «William Vollmann - The Royal Family» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2000, ISBN: 2000, Издательство: Penguin, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Royal Family

- Автор:

- Издательство:Penguin

- Жанр:

- Год:2000

- ISBN:9780141002002

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Royal Family: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Royal Family»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Royal Family — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Royal Family», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Look, said John. When all’s said and done, I don’t want you ending up as some homeless bum, okay?

I don’t figure it will come to that, said Tyler palely.

I don’t believe we’re wanted here, said Mrs. Simms. This is such an extraordinarily personal conversation.

You hang out with homeless people, don’t you? I mean, those crack whores, those tramps…

In John’s eyes, Tyler thought he saw an appeal: Don’t say anything about Domino in front of Celia. Please.

(Smooth white shirts and soft black trousers, shiny black shoes — that was how Domino thought of John. She gave him good marks for money, cleanliness, and deportment. But now he was trying to run away from her. It was only natural that she would refuse to let him go. And he had gone.)

Yeah, some of them are a bit transient, he said.

The homeless guys that get forced into that lifestyle, I don’t really have a beef with them, his brother announced. The ones that choose it really piss me off.

Something in the pomposity, in the sheer chutzpah of this man’s assertion, why, it reminds me of Domino, Tyler realized. He clenched his fists and said: How’s Brady?

Fine. I hear you parted on bad terms.

Well, he laid me off.

He fired you.

This is the atmosphere I always come back to, Celia told Mr. and Mrs. Simms with an ugly smile. — They say you can’t escape your background, so this must be my background.

I had no idea it would be like this, said Mrs. Simms.

John, he laid me off. We had an agreement, and—

I’d like to see a copy of that agreement.

Now who’s spying and snooping?

I want to help you, Hank, John pleaded.

Oh, you’re the better man, Tyler said. You’ll do fine. You don’t lie to people the way I do. You make good money. You wear nice neckties. You take care of yourself and others…

Do you want me to forgive you or not?

What kind of forgiveness would it be, if it were up to me? Anyway, it’s too late.

How do you know what too late is?

You want to know about too late? Fine. I figure that since this is May, Irene was already five months pregnant this time last year, Tyler said defiantly.

| 450 |

He shook John’s hand goodbye. Celia wouldn’t look at him. He’d already dropped by the funeral parlor with his cashier’s check. It pleased him to feel that he owed John and his mother nothing now. He would make his own way, or not. He almost felt sorry for John, because it would have made John so happy to help him. Let John help Celia. He did not sleep in his mother’s house. John and Celia were there. In his motel there was a Bible in the bedside drawer, and he opened it to Genesis and read: Abraham journeyed toward the territory of the Negeb, and dwelt between Kadesh and Shur; and he sojourned in Gerar. Outside, he heard a train go clinking musically by. The place-names, ancient and strange, clattered in his mind like boxcars. He thought upon his doings, and was satisfied with what he had done.

Early next morning, anxious to escape from his mother’s grave, he packed his suitcase, guzzled two styrofoam cups of coffee in the lobby, checked out and drove toward the freeway, wondering whether he ought to visit Irene’s grave in Los Angeles, but somehow that seemed of no importance. His mother was gone, Irene was gone; soon the Queen would be gone. They shall die of deadly diseases, the motel Bible had said. They shall not be lamented, nor shall they be buried; they shall be as dung on the surface of the ground. He rejected this. John had invited him to breakfast. He and Celia were almost certainly still sleeping in each other’s arms. Tyler had made up his mind that the best policy would be to make Celia hate him, and to accomplish this in an unostentatious manner which would give John no grounds for suspicion. It was not that he thought himself in danger of propositioning her; he would much have preferred to win a new friend. But any such friendship would damage the pattern of his brother’s tranquility. Best to be gone, unlamented, where he could lie upon his Queen’s breast like dung.

Now he was approaching Loaves and Fishes on Sixteenth Street where the bleak-packed stones on the dirt comprised a pavement which plateaued up above the overpass by the railroad tracks which ran dully perfect beneath the clouds, and a longhaired girl wheeled her bicycle, whose basket was full of clothes, her husband or boyfriend in camouflage stopping, reaching under the fence for his bottle of beer. Tyler felt restless. His energies could settle on no firm object now that he had given up Irene’s grave. He longed to eavesdrop on this couple, or photograph them, or merely go steal mail from anybody’s mailbox. Displeased with these yearnings, he parked, locked all four doors, and walked through the underpass tunnel, in which somebody had painted the words WHITE POWER. Where was he going? Between Kadesh and Shur. Slowly he retraced his steps. Before he knew it, he had walked all the way to the river where it had just rained and the anise was already shoulder high and there were purple blossoms everywhere. The water trembled with blue stains between cloud-reflections. Bending down, he picked up a little plastic liquor bottle frosted by stale crack smoke.

An old panhandler stood holding an illegible message like one of the lost Gnostic Scriptures or Dead Sea Scrolls. He glared at Tyler and said: Repent.

Repent what?

Everything, brother.

I already do.

Then you’re saved. Move on, so others can see the message.

Tyler shrugged. He moved on. Then, having considered, he returned to the panhandler and said: You know what? I don’t repent of absolutely everything. There’s a dead woman I love, and I also love my Queen. I don’t repent of either of those loves. So what do you say to that, hey?

So you’re damned. Move aside.

What about my mother? She just died.

Did she repent?

I wasn’t there.

Then why ask me? Move on.

You know what, brother? I’m your enemy. I bear the Mark.

I love my enemies, because Jesus told me to. Move on.

Where do you want me to move to?

Hell.

I get it, sniggered Tyler, and he wandered off, rolling his eyes.

| 451 |

It was a Sunday warmly fogged over. He wanted to be home even though he wasn’t sure whether home meant being with the Queen or something else. Actually, he dreaded seeing the Queen. The uneasy disorganization of her hive had begun to affect him, and the loving guidance he’d previously received from her now seemed unreasonable to demand; he was selfish; she must be tired; for her sake he wanted to go away but feared that such an act would likewise be a kind of betrayal. Suddenly he remembered how late one winter afternoon, it must have been in December, he had met her amidst the immense brick and concrete buildings south of Market, some of whose roofs bore smokestacks like giant cigarettes, or metallic whirling onions for ventilation; at sunset those cubes all had pulled down as snug, heavy, thick, and safe as a good girl’s underpants those steel accordions graffiti’d with signs and signatures resembling snarled wires — pulled down snug, yes, thereby sealing off those loading docks which on whores were known as cunts. Against the steel-shuttered face of a shop whose owner had gone to bed hours since, she who was his Queen was waiting in a long pale coatdress which came almost down to her sneakers, and she was almost smiling, with light weeping from her eyes. That was the last time he had seen her happy. (She always laced her breasts tight against her chest.)

Just as the Queen’s long insectlike eyelashes upcurved whenever she nodded off, so Tyler and his car ascended into dreaminess. Wasn’t this cityscape made up of trivialities? Sometimes it was foggier than today, and the Bay Bridge’s silver girders stood alone in whiteness in much the same way that at noon Capp Street was always so wide and white, the walls of its little houses like naptime sheets. Sometimes the weather was clear, and then the city offered itself so beautifully to his gaze, although of course what one saw of it from the Bay Bridge was only John’s San Francisco, perhaps Brady’s, not his; he didn’t belong among the financial district’s computer punchcard facades whose coldness and sharpness the fog had pasteled into utopia. He drove nearer. San Francisco’s streets were inlaid with little white apartment squares. The window-pitted faces of those skyscrapers smiled on him, almost close enough to be caressed. Passing the Harbor Terminal, he descended into the zone of billboards, riddled with an anxiety which almost made his teeth chatter. There were too many secrets inside him which might fall out with a loud rattling noise, all his fear and shame corroding off rusty metal parts of his insides, so that they might clank and give him away. He had to move on tiptoe all the time. Sooner or later he’d trip up.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Royal Family»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Royal Family» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Royal Family» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.