I see the mask of beauty, and I want to kiss it. Then what? I taste wood.

Drawn to the mask of love, I give myself. My fulfillment will be separation. One will stop loving the other; or one will die. Wait awhile; wait awhile.

No, I reject that! I want grace that lasts forever…

Then down with me to the Sea-God’s palace! Having married an immortal, I wait awhile, wait awhile, but then I long for life, the outstretched red and gold fan whirling, the figure so fantastic, spectacular and immobile even as it moves. If I get desperate I’ll open Urashima’s box. The actor’s right arm rises to the crown, and suddenly…

A face is a mask; a lovely face is a lovely mask; even if I kiss it I can never “possess” it even though my desire insists that I can; but because desire is hunger, then if possession were actually possible than it would partake of consumption; therefore, how excellent a thing is a mask! My eyes drink of it without depleting it.

Is the heterosexual attachment of a man to a woman who unbeknownst to him retains some of a man’s attributes any more of an illusion than any other attachment? Noh asserts that all attachments are equally useless, even harmful. I myself cannot help but feel that Kaguyahime’s abandonment of her foster parents was cruel. But it was cruel because they were still attached to her. — Well, then, should they have stayed in exile on the dull side of the rainbow curtain, eternally declining to perform their roles and be attached?

Grace creates attachment. Would it be better, then, to remain an ape in a cage, incapable of appreciating grace?

All attachments must end. A famous poem in the Tales of Ise asks the moon why it must disappear so rapidly, leaving us unslaked. Already the actor has gone behind the rainbow curtain to remove his mask! Well, then is it preferable to absent myself from the performance? I could remain unattached in Akashi, determinedly distant, ironical, dreary and irrelevant, like some fading Noh under-kimono dedicated primarily to the representation of foreigners and warriors in light armor (purple, with eight-feathered fans between waving golden lines); awaiting my end without anticipation or fear; they’d call me beauty’s teetotaler… If I see only insufficiencies in art, will I have maintained myself in the proper environment?

In the Gnostic Scriptures we find a writing called “The Thunder: Perfect Mind,” in which God is female: wife and whore, barren mother of all contradictions. She says: “For many are the pleasant forms which exist in numerous sins… and fleeting pleasures, which men embrace until they become sober and go up to their resting-place. And they will find me there, and they will live, and they will not die again.” If I withhold myself from sin in Akashi, will I finally be able to attach myself to beauty once she invites me into the capital? Just as a kimono pulses around a woman’s white ankles when she goes upstairs, so the robe of Kaguyahime allures me as she ascends to her lunar home. Should I blind my recollections to it until I am called, if that ever happens? But what if I am no longer fitted for beauty by then? Doesn’t it take a lifetime to comprehend the flower of peerless charm? Even then, how much can this ape hope to learn when grace so often follows the model of one family’s Noh theater which I saw reconstructed in Kanazawa: partitioned chambers for the elite enclosing the open tatami space for mass audiences? — Where would I be? Since I’m from Akashi, they’d surely show me to my proper environment.

Even an Edo dweller might be able to visit the theater only once a year, perhaps dressing one’s hair in a special way, awaiting the moment of passing through the “mouse gate” and entering another world: To the seductive, almost leering wavering of many shamisens, a snowfaced Kabuki warrior throws back his head and raises his parasol! Upon the stage bridge begins a slow parade of a Kabuki courtesan with her retinue. — And then? — Back to Akashi.

There is a geisha song about a pair of butterflies tied to each other by dreams which cannot come true; they flutter to “the end of the end.” The commentary explains that two lovers who could not be together in this floating world killed themselves, and became butterflies. What then? Why, at the end of a butterfly’s life they reach the end of the end.

All attachments must end. And every time I see a performance of “Matsukaze,” I will see it end in the same way, down to the very last gesture. About this fact, Mr. Umewaka once remarked: “It’s more difficult to always do the same thing than to change; we chose to do the difficult thing.”

And I, too, would rather do the difficult thing. I prefer to experience grace even though I must lose it and fall back down to my death in Akashi; I defy my proper environment. My dream is over; last night’s autumn rain has ceased; now nothing remains but the wind in the pines. But I remember when Komachi’s throat was as white as a new tatami mat, and someone who proved cruel and treacherous still loved me. My proper environment may soon be a waste of pampas grass where the wind sings through my eyesockets, but I’ll turn away from that while I can; why not listen to the song of the capital bird?

Indeed, it seems to me, perhaps because I am not a shite but a waki , that my way was never a sliding path upon the polished stage of a Noh theater, but a pilgrimage through places far more irregular than the stepping stones in the gravel paths of the Shoren-in Temple; and on many of the occasions when I have passed into Japan, I have visited spots where ghosts in various guises have told me of the past. Against all Noh’s warnings, I have always sought out attachments. I seek to know these ghosts so that they can allure me all the better. The dances of Kofumi-san and the faces of all the maikos of Gion who shine like jewels in the darkness, the loveliness of Suzuka-san as she transforms herself, the sweet happiness in the dances of Masami-san, the flashing golden fan of Mr. Mikata, the slowly, slowly turning head of Mr. Umewaka in a ko-omote mask, the warmly neutral eyes of Konomi-san, the shadow of Konomi-san’s neck and wig upon the wall of the teahouse, they tell me stories to which I cling far more than a true courtier from the capital would find needful; for all that I, a man, client, spectator, reader, foreigner can grasp is a single instant; whereas their performances exist far before and beyond me. Although you may see me as a sliding, passing consciousness upon the smooth stage of these printed pages, I believe that I have actually been places. Once in Pakistan I heard the muezzin calling in the darkness as rain flowed down — rain? No, it was the simultaneous ablutions of the faithful, running down pipes in walls all around me. The street lay crisp beneath the full moon. A horse canter-clopped by. Then the chorus of prayer-song arose from the mosque, more unearthly to me than the raptures of a Christian choir because the tonal scale was so different; it reminded me of the wind-soughs and river-music I’ve sometimes heard alone in my tent in the Arctic. It echoed weirdly; it might have been a crew of sailors singing far away on a storm-tossed ship. And all these things that I thought I heard were in reality a Noh chorus which sings to you what it is that I, a mere construction of words, claim to perceive.

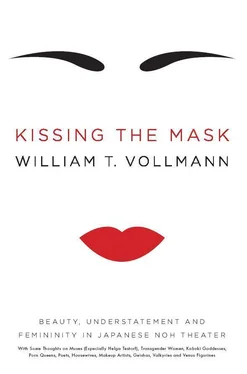

KISSING THE MASK

“To see with the spirit,” writes Zeami, “is to grasp the spirit; to see with the eyes is merely to observe the function.” What lies beyond function? Is it what lies behind the Noh mask? If so, are we supposed to see it?

If her face is a mask, then perhaps the vulva of the woman whom I love is a square lacquered box whose white butterflies resemble both pointed-tipped hearts and the black-ribbed fans of women; these insects browse on silver-gold brier roses in a blue-muted darkness, reminding me what a certain lady wrote in 1818: “Those who dedicate themselves to pleasure realize that they are like insects playing in the flowers, but find it difficult to forsake these frivolous habits.” Meanwhile, every one of this box’s decorations is misted toward silver, as in Shun’e’s advice to Chomei.

Читать дальше