And yet that house with its erotic luxury and hallmarks of foreign possibilities, that cosmopolitan palace which Isao would have hated, what a perfect womb for a creative mind! To be sure, he could have become soft and fat living in that house (and suddenly I think with more sympathy of Urashima, immortal so far, dwelling endlessly underwater with the Sea-God’s daughter). In his study stand Japanese brushes in a lacquerware cylinder, an elegantly slender calligraphy box, a block of scarlet ink for what I think is a stamp or seal; with those objects perhaps he could have incarnated himself into a living exemplar of the Japanese tradition which he imagined that he had to die for. He might have chosen any number of fates. And it may be significant that the tense, gruesome Runaway Horses , whose hero kills himself more or less with Mishima’s method, is not the final novel of the tetralogy, but the second. What if Mishima, like the ghost- shite of many a Noh play, had outlived his own death? Honda himself is condemned to outlive Isao’s seppuku for two more volumes in which nothing nearly as dramatic will occur. In the third volume, The Temple of Dawn , he witnesses what he believes is Kiyoaki’s reincarnation in the person of a beautiful, mysterious Thai princess. Mishima’s mood becomes richly tropical here, and the discourses into Buddhist theology, which irritate some readers, to me evince a last flowering of intellectual excitement on Honda’s part as he continues to attempt to find, and Mishima to convey, perhaps to feel, the meaning of existence. But halfway through this novel, the famous aridity has already set in. Lovesickness, ideological rapture, and divine mysteries are done. The final book, The Decay of the Angel , exudes a suffocatingly existential quality. It’s all about waiting for death — not the joyfully fanatical death of Runaway Horses , which Mishima tried unjoyfully to die, but the death of the white ants. Unable to move forward to oblivion, the shite chants out nausea and putrefaction. Reading The Temple of Dawn always makes me feel that the tetralogy’s end, and Mishima’s corresponding finish, were not preordained. 1The enigmatic little Thai princess offers the prospect of something different, something not only almost as erotic as suicide, but perhaps more elusive, something worthwhile enough to warrant not killing oneself while one tries to uncover it. Very possibly, if The Temple of Dawn is any indication, this something could have been religion or philosophy. I wonder how feverishly Mishima hunted for it in his wood-clad study with the bookshelved walls. 2He failed to find it, and that is why every year on 25 November, the white-clad Shinto priests lay down their prayer-streamers on the altar, which resembles a tabletop model of a round-towered castle, and the blood-red disk of the Hinomaru flag hangs above them in the darkness beside Mishima’s portrait.

MISHIMA’S KOMACHI

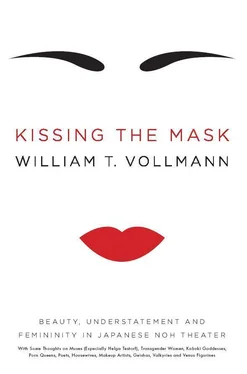

In the shade of his sensational end, Mishima’s Noh plays often go overlooked.

Of the five which I have been able to read in translation, three fall considerably short of their originals. Only his “Hanjo” is clearly superior. All of them gleefully defy Zeami’s edict that “one must not copy the vulgar manners of common people.”

In shocking contradistinction to the classical Noh aesthetic of yugen , Mishima begins his “Sotoba Komachi” as follows: “ THE SET is in extremely vulgar and commonplace taste, rather in the matter of sets used in operettas .” In other words, “the white ants were there from the start.” One of Mishima’s hallmarks, like Poe’s, is nastiness .

In the original, as in the sister Noh plays, Komachi is a pathetic character whose echoes of her past beauty and arrogance render her grandly pitiable — and more, for having outlived the false flower of her youth she may win through to enlightened non-attachment. But in Mishima’s version she becomes, as women so often do in his work, an impure devourer whose weapons include ambiguity and hypocrisy. Mishima’s hero-protagonists are resolute. His heroines are the enemies of resolution.

One could write a diverse catalogue of the little avarices which occur when poverty marries old age. But when this ant-eaten Komachi of his counts over her hoard of cigarette butts, this seems not only appropriate to an aged beggar, but germane to the younger Komachi whose absence shines from behind the rainbow curtain — for didn’t she collect from Fukakusa her utmost toll of those hundred fatal nights? Mishima recapitulates her tale on a gruesomely petty scale. I, glorifier of my attachments, reject to my utmost power Noh’s assertion that clinging to whatever moves becomes torture — but Mishima’s Komachi is a horridly convincing argument against me. What makes her horrid is that he has stolen her grace away. 3In this anti-Noh of his, the Poet who stands in for Fukakusa insists: “The park, the lovers, the lampposts, do you think I’d use such vulgar material?” Mishima uses it with glee; Komachi embodies it, all the while assuring us that nothing was not vulgar once. The Poet, who himself lacks any sweetheart, loves lovers because they seem to each other more beautiful than they are. To this Komachi replies that those who keep such illusions are actually dead: Boredom and disgust prove that one has come back to life.

Here is an example of Mishima’s typically morbid version of aware . Komachi looks around her at the loving couples in the park and remarks: “They’re petting on their graves. Look, how deathly pale their faces look in the greenish street light that comes through the leaves.”

And presently one even finds a tiny bit of yugen , although it reminds me of some grim voyage to Hel in the Norse Eddas: “Shadows are moving over the windows, and the windows grow light and dark by turns with the shadows of the dance. So wonderfully peaceful — like the shadows cast by flames.”

Mishima continually implies that the beauty of femininity’s mask is not merely delusory, but dangerous, distracting, voracious: the ruination of male energy. (As it happens, he forgives the loveliness of the onnagata who gazes demurely down while the red-painted outer corners of her eyes curve impossibly up.)

Did Fukakusa no Shoso die a worthwhile death? In Spring Snow , Kiyoaki fruitlessly visits again and again the woman who, her virginity stolen by him, has been led to take the tonsure and renounce him forever. Like Komachi’s lover, he dies at last of exposure. There is, to my mind at least, an element of self-destructive stupidity in Kiyoaki’s doings; but what I interpret as the author’s accomplished irony may be something else, given how he ended his life (how horrible if he had felt “ironic” even then!). And Captain Fukakusa in Mishima’s “Sotoba Komachi” has certainly been warned by the old witch herself not to let himself be allured. He seems to inflict the spell upon himself, and therefore to be more self-aware, profounder, than his exemplar in the traditional texts. As for Komachi, like so many Mishima heroines (although certainly not all of them), she is not much more than evil, and therefore far inferior to her original. When Mr. Kanze portrayed Komachi in her old age I could almost see the white triangles of snow in the joints of the bamboo-grove at the Shoren-in, or the way that in late spring the moss of the Shoren-in mottled and marbled with fallen cherry blossoms; 4whereas Mishima’s Komachi is simply an ogress — or is she? The rule is this: Call her beautiful and you die. She sportingly warns the Poet of this again and again even as she entices him to dance. But is he perhaps already dead? He promises to meet her here in a hundred years, when she will have grown old as he will not. So could he be the ghost of Fukakusa? Tonight has dreamily become the hundredth night, so Komachi must give herself to the Poet, at which prospect he feels simultaneously happy and disheartened. But then he says: “If I think something is beautiful, I must say it’s beautiful even if I die for it.” And so he dies, and Komachi calmly sits counting up her cigarette butts.

Читать дальше