when one gazes upon the autumn hills half-concealed by a curtain of mist, what one sees is veiled yet profoundly beautiful; such a shadowy scene, which permits free exercise of the imagination in picturing how lovely the whole panoply of scarlet leaves must be, is far better than to see them spread with dazzling clarity before our eyes.

I read these words without any sense of alienness, perhaps because as a child I sometimes read the Bible, sensing even then, as Auerbach expresses it, that the sublimity of Genesis and kindred Scriptures “is not contained in a magnificent display of rolling periods nor in the splendor of abundant figures of speech but in the impressive brevity which is in such contrast to the immense content and which for that very reason has a note of obscurity which fills the listener with a shuddering awe.”

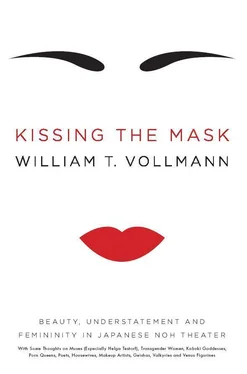

In short, the magic of understatement — beautiful mystery — allures us everyhere. When I glimpse a beautiful garden behind a wall, I experience the tantalizing category of appreciation called miekakure . When I longingly remember some metonymic attribute of a place where I can no longer be, that is wabi , the loveliness of loneliness. 4When I fall in love, I am allured, abandoned and enriched by fantasies of entities which dwell beyond me and hence are greater than I. When my heart hurts me in longing for the woman I love, it is because there will always remain more of her than I can know, possess, or surrender to. In short, I see her through a changing fog. And when a Noh mask haunts me from the stage, the mists of austerity and stylization render that female presence likewise awesomely remote while still less attainable.

It is past time to formally introduce the tools which Noh employs in the service of those veiled gorgeousnesses of infinitude. If you are familiar with Noh, this chapter and the next (like all the others) may conveniently be skipped. Otherwise, please be reminded once again that these oversimplifications are an ape’s utterances. For example, nearly all of the following sentences ought to end with “with the exception of ‘Okina.’ ”

ROLES

The waki or witness appears first on stage. He is, like all of us who live, a traveller in an unknown land, far from the capital. (Dante: In the middle of the journey of our life I lost my way. ) Sometimes he is an imperial messenger, sometimes a monk. In “Sumidagawa” he is a ferryman who has crossed the river any number of times; this does not make him any less vulnerable to unexpected irruptions. The waki of “Kinuta,” which play received mention in the previous chapter, is none other than the husband of the woman who dies from neglect. He worries about her and wishes to return to her, but worldly compulsion (a lawsuit, and then there is an intimation of a liaison with the younger housemaid) keeps him at the capital until she dies of grief. What next? He decides to invoke her ghost, “to call her to the curved bow’s tip, / poor soul, so that we two may speak.” And here she comes, feebly creeping onstage as far as the first pine. The unknown is upon us, bearing witness to itself in poetry sung and danced. And the witness to whom witness is borne, our representative, is the waki . Another gloss on his function is “watcher on the side.” He frames the tale with contexts and introductions; he narrates. Then, like the implied first-person voice that introduces Madame Bovary , or the somewhat plodding gentleman at the beginning of Wuthering Heights , he watches from the side. His costume and demeanor accordingly aim for a subdued impression. He wears no mask.

Zeami for his part remarks that “a waki fulfills his function insofar as he follows what is good and what is bad alike,” even a bad shite . In other words, while he might express, for instance, compassion, he does not judge. And when he is a priest, what has been called his determined immutability may achieve the power to liberate another character from the miseries of attachment.

On occasion, he figures in tropes beyond Noh. Kawabata’s passive yet sensitive protagonists have sometimes been compared to waki s. Discussing The Narrow Road to the Deep North , a scholar concludes that Basho must have been “just as interested in meeting the ghosts of men who had lived there long ago as in meeting his contemporaries.” Accordingly, our scholar likens him to a waki , who is “in many cases an itinerant monk who invokes the ghost of a past local resident wherever he goes.”

The waki is sometimes accompanied by attendants, the wakizure . In the immortal words of Royall Tyler, “these generally have little to say.”

Sometimes Noh employs a koken , a child actor, often as an object rather than a subject of the action. Spectators might also see a kyogen , who unlike the actor of a comic kyogen play relates some aspect of the story that has not been elucidated more explicitly. His recitation may, however, be the merest recapitulation, in which case the shite is probably busy changing mask and gown.

The shite is “hero” or “heroine” of Noh, but I have never been able to “identify” with a shite the way I can read myself into the soul of a book’s protagonist. This must not be merely a matter of cultural distance; when I reread The Tale of Genji I get absorbed into the psyche of the Shining Prince, and at times, into that of Lady Murasaki herself. But the shite sings to me from the unknown land behind the rainbow curtain.

Shite means simply “actor.” His role sometimes gets subdivided into two: maeshite and nochijite , meaning respectively the shite of the first part and of the second part. He may have tsure , companions analogous to wakizure , but these are generally more active and ornately turned out than the latter. They may wear masks when playing female roles. Occasionally they even eclipse the shite . In “Semimaru,” for instance, the eponymous tsure appears just as prominently and more constantly than the shite , his sister Sakagami. Had I been told that Semimaru were the shite , I would certainly not have known better.

It is, of course, the shite who epitomizes masked and costumed gorgeousness. Although I have seen him in a chorus, it is certainly in his shite role that I think of Mr. Umewaka.

In “Kinuta” the maeshite is the pining wife of the first act, and Zeami specifies that she be represented with a fukai mask, which pertains to a middle-aged woman; the nochijite is her bitter spirit, who may appear to us through the vehicle of either a deigan or a yase-onna mask, both of which are associated with “vengeful female ghosts.” Other shites include the once-beautiful hag Komachi in “Seki-dera Komachi,” the distraught mother in “Sumidagawa,” the abandoned sweetheart Pining Wind in the eponymous “Matsukaze,” and the old man ( maeshite ) who turns out to be the Dragon God ( nochijite ) in “Kasuga ryujin” (which gets discussed in the next chapter).

The shite ’s situation, with its resulting dramatic and metaphysical possibilities, brings to mind a great critic’s comment about the souls in the Inferno :

From the fact that earthly life has ceased so that it cannot change or grow, whereas the passions and inclinations which animated it still persist without ever being released in action, there results as it were a tremendous concentration. We behold an intensified image of the essence of their being…

And this goes far to explain the melancholy of so many Noh plays. The desperately impoverished reed cutter in “Ashikari,” whose wife gets rich and returns to bring him lovingly to the capital, is an exceptionally fortunate shite , and it is all the stranger that Zeami wrote this play. “Shunkan,” once attributed to Zeami and now tentatively to Motomasa or Zenchiku, better fits the mold: On a place called Devil Island, three exiled Genji factionalists await, with very little hope, their pardon and recall, “the only wine a valley stream, and flowing with it streams of tears.” In the end, two men will be rescued, and Shunkan will be left alone to die a hideous death. 5“ ‘Wait a while, oh! wait a while,’ say the far voices growing dimmer”; they promise to plead in the capital for his return, but never will. Indeed, many plays (like many geisha songs) are about waiting; and the weary pounding of the fulling block, which we have already discussed in regard to “Kinuta,” appears also in “Torioi-bune,” when the wife, who like the heroine of “Kinuta” waits many years for her husband’s return from the capital, specifies one item of her misery as “the dull thud of the fulling block, in the chill of night.”

Читать дальше