in themselves

and the sun and the moon and the stars

his mind should enter into the seasons

he should go

among many people

in many places

and learn their languages 10

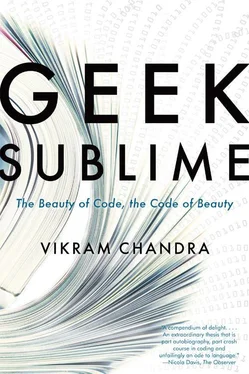

I have a sabbatical coming up. My plan is: (1) write fiction; (2) learn a functional programming language; and (3) learn Sanskrit.

In Red Earth and Pouring Rain one of the characters builds a gigantic knot. “I made the knot,” he says.

I made it of twine, string, leather thongs, strands of fibrous materials from plants, pieces of cloth, the guts of animals, lengths of steel and copper, fine meshes of gold, silver beaten thin into filament, cords from distant cities, women’s hair, goats’ beards; I used butter and oil; I slid things around each other and entangled them, I pressed them together until they knew each other so intimately that they forgot they were ever separate, and I tightened them against each other until they squealed and groaned in agony; and finally, when I had finished, I sat cross-legged next to the knot, sprinkled water in a circle around me and whispered the spells that make things enigmatic, the chants of profundity and intricacy.

When I wrote that book, when I write now, I want a certain density that encourages savoring. I want to slide warp over woof, I want to make knots. I want entanglement, unexpected connections, reverberations, the weight of pouring rain on red earth. Mud is where life begins.

Like palm-leaf manuscripts, the worlds the writer creates will finally be destroyed, become illegible. At least until they are re-excavated and become alive again within the consciousness of a future reader. I don’t worry too much about whose work will “last,” and if mine won’t. I do think endlessly about the shapes of stories, about the tones and tastes that will overlay each other within the contours. I don’t much like perfect symmetry, which always seems inert to me. The form of art rises from impurity, from dangerous chaos. When I can find perfection and then discover the perfect way to mar that perfection, I am happy. As a creator, I want to bend and twist the grammar of my world-making, I want crookedness and deformation, I want to introduce errors that explode into the pleasure of surprise. In art, a regularity of form is essential, but determinism is boring. When I am the spectator, the caressing of my expectations, and then their defeat, feels like the vibration of freedom, the pulse of life itself.

Abhinavagupta’s assertions about rasa-dhvani may remind Western readers of T. S. Eliot’s objective correlative:

The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding … a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked. 11

This may not be simply a case of two thinkers separated by centuries coming independently to similar conclusions; Indians like to point out that Eliot read substantially in classical Indian philosophy and metaphysics during his time at Harvard, certainly enough to have encountered rasa and dhvani. In 1933, Eliot wrote:

Two years spent in the study of Sanskrit under Charles Lanman, and a year in the mazes of Patanjali’s metaphysics under the guidance of James Woods, left me in a state of enlightened mystification. A good half of the effort of understanding what the Indian philosophers were after — and their subtleties make most of the great European philosophers look like schoolboys — lay in trying to erase from my mind all the categories and kinds of distinction common to European philosophy from the time of the Greeks. My previous and concomitant study of European philosophy was hardly better than an obstacle. And I came to the conclusion …

… that my only hope of really penetrating to the heart of that mystery would lie in forgetting how to think and feel as an American or a European: which, for practical as well as sentimental reasons, I did not wish to do. 12

Eliot’s reluctance — or inability — to “think and feel” across a cultural divide, even as he borrowed certain idioms and ideas ( “Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata. / Shantih shantih shantih” ) was rooted in his recognition that this would require self-transformation at an elemental level, a departure from comfortable, familiar certainties. To someone raised in the tradition of Western analytical philosophy, encountering the goddess in philosophical texts might indeed induce terror, especially if you think all mysteries can be penetrated to the heart; it is no coincidence that Anuttara is sometimes pictured as a “hideous, emaciated destroyer who embodies the Absolute as the ultimate Self which the ‘I’ cannot enter and survive, an insatiable void in the heart of consciousness.” 13The terrible goddesses demand that you sacrifice, that you eat foreign substances, that you let the impure and chaotic penetrate you. The ishta-devata or personal deity that you worship will shatter you and remake you.

And yet, when the thunder speaks, we all come away reading a message into the sphota , the explosion of sound. Eliot heard what he needed to, and used it in his art and thought. Programmers create elegant techniques like event-sourcing, they make beauty in code, but many — like Paul Graham — use the language of aesthetics and art to describe their work without engaging with the difference of artistic practice, without acknowledging that the culture of art-making may in fact be foreign to them. Eliot was aware that there was a mystery that he wanted to avoid; programmers, on the other hand, often seem convinced that they already know everything worth knowing about art, and if indeed there is something left for them to comprehend, they are equipped — with all their intelligence and hyperrationalism — to figure it out in short order. After all, if you decompose an operation into its constituent pieces, you can understand the algorithms that make it work. And then you can hack it. Therefore, to make art, you don’t have to become an artist — that, anyhow, is only a pose — you just analyze how art is produced, you understand its domain, and then you code art. And, conversely, when you are writing code using the formal languages of computing, you are making something that aspires to elegance and beauty, and therefore you are making art.

Abhinavagupta’s description of poetic language and its functions reveals the hapless wrong-headedness of these kinds of facile cross-cultural equivalencies: code is denotative, poetic language is centrally concerned with dhvani , that which is not spoken; the end purpose of code is to process and produce logic, and any feeling this code arouses in an immediate sense is a side effect, whereas poetic language is at its very inception concerned with affect. Rasa arises from the fluctuations of feeling produced by manifestation, so to be aesthetically satisfying, even a play about a meeting between a physicist and his mentor must imbue the theories of physics with personal and emotional ballast, must make the equations resonate with memory. And so on: code may flirt with illegibility, but it must finally cohere logically or it will not work; the language of art can fracture grammar and syntax, can fail to transmit meaning but still cause emotion, and therefore successfully produce rasa.

The “hackers are artists” manifestos and blog posts gloss over these differences, and also remain quite silent about the processes that produce these culminations. For my own part, as a fiction writer who has programmed, thinking and feeling as an artist is a state of being utterly unlike that which arises when one is coding. Programming is very hard, and doing it requires a deep concentration in which I become quite unaware of my surroundings and myself. When I am trying to follow a bug, to understand its origins, time collapses. I type, compile, run, decipher a stack trace, type again, compile, run, and I look up and an hour and a half has gone by. I am thirsty, my wrists are aching, I should get up and stretch, but I am on the verge of discovery, there is one more variation I could try. I type again, and another half hour is gone. There is the machine, and there is me, but I am vanished into the ludic haze of the puzzle. The programmer Tom Christiansen put it succinctly: “The computer is the game.” 14

Читать дальше