The earliest available text in Sanskrit is the Rig Veda, dating — according to current scholarly consensus — from around 2000–1700 BCE. 4The Rig Veda, and the other Vedas that followed — the Sama, Yajur, and Atharva Vedas — were considered to be eternal, uncreated, “not of human agency” ( apaurseya ), and “directly revealed” ( shruti ) to the seers; these qualities distinguished them from all other religious texts, which were “what is remembered,” smriti. The language that these Vedic wisdom texts were orally transmitted in — not yet called Sanskrit — was therefore also eternal, uncreated, devavani —“the language of the gods.” The truths that the Vedas embodied lay not only in the sense, the verbal meaning, but also in the sounds, the pitch, the tonality, the meter. Therefore it was vitally important to maintain these qualities from generation to generation, to guard against linguistic deterioration and slippage. Among the auxiliary sciences developed as “limbs of the Veda,” vedanga , there were several that ensured faultless reproduction across the years, including phonetics, grammar, etymology, and meter. Accurate preservation of the Vedas earned spiritual merit. Grammar was the “Veda of Vedas,” the science of sciences; it was called vyakarana , simply “analysis,” and was the foundation of all education. The Brahmins, the priestly caste, were trained rigorously in the cultivation of memory and linguistic expression. The effort was successful; the Vedas are chanted today exactly as they were almost four millennia ago, complete with archaic tones and usages present nowhere in the Sanskrit that followed.

A single text from about 500 BCE, the Ashtadhyayi (Eight chapters), is usually credited with forming this later “classical Sanskrit”; with this one book, the grammarian Panini created the fields of descriptive and generative linguistics. Drawing on the sophisticated regimes already developed, he attempted to create a “complete, maximally concise, and theoretically consistent analysis of Sanskrit grammatical structure.” 5His objects of study were both the spoken language of his time, and the language of the Vedas, already a thousand years behind him. He systemized both of these variations by formulating 3,976 rules that — over eight chapters — allow the generation of Sanskrit words and sentences from roots, which are in turn derived from phonemes and morphemes. 6In addition to these rules, he provides a list of all Sanskrit phonemes, along with a metalinguistic scheme that allows him to refer to entire classes of phonological segments with just one syllable; a classified lexicon of about two thousand Sanskrit verbal roots along with markers that encode the properties of these roots; and another classified list of lexical items that are idiosyncratically acted upon by certain rules.

The rules are of four types: (1) rules that function as definitions; (2) metarules — that is, rules that apply to other rules; (3) headings — rules that form the bases for other rules; and (4) operational rules. Some rules are universal while others are context sensitive; the sequence of rule application is clearly defined. Some rules can override others. Rules can call other rules, recursively. The application of one rule to a linguistic form can cause the application of other rules, which may in turn trigger other rules, until no more rules are applicable. The operational rules “carry out four basic types of operations on strings: replacement, affixation, augmentation, and compounding.” 7

In addition to ordered rules, Panini also pioneered the use of linguistic “zero elements” for constituents posited in analysis but omitted in usage, as in the sentence “Women adore him,” in which the determiner “the” is assumed to precede “women.” 8He also created a metalanguage comprising special technical terms and markers which enabled him to speak precisely and unambiguously about the language he was analyzing. 9

In Sanskrit, word order is not important other than for stylistic purposes; the verb can be placed anywhere in a sentence. So the Ashtadhyayi concerns itself mainly with word formation. When it does concern itself with sentence formation

Panini accounts for sentence structure by a set of grammatical categories which allow syntactic relationship to be represented as identity at the appropriate level of abstraction. The pivotal syntactico-semantic categories which do this are roles assigned to nominal expressions in relation to a verbal root, called karakas. A sentence is seen as a little drama played out by an Agent and a set of other actors, which may include Goal, Recipient, Instrument, Location, and Source. 10

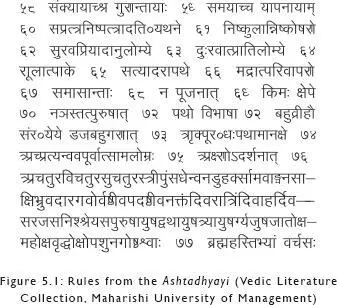

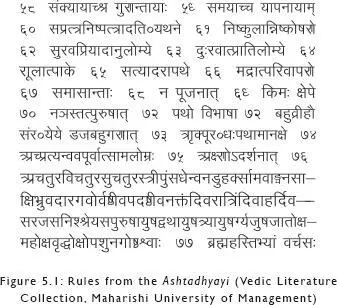

The rules of the Ashtadhyayi are extremely concise; here are numbers 58 through 77 of the fifth chapter: 11

Only a few rules are more than two or three words long, so the entire rule set comprises only 32,000 syllables and fits into about forty pages of printed text. 12The economy of Panini’s prose is such that a recent translation into English ran to over 1,300 pages. Panini somehow caught, the saying goes, an ocean in a cow’s hoof print. With this very finite analysis, Panini not only comprehensively described the functioning of his language, he also opened it up to infinity. S. D. Joshi points out:

The Astadhyayi is not a grammar in [the] general Western sense of the word. It is a device, a derivational word-generating device … It derives an infinite number of correct Sanskrit words, even though we lack the means to check whether the words derived form part of actual usage. As later grammarians put it, we are lakṣaṇaikacakṣuṣka , solely guided by rules. Correctness is guaranteed by the correct application of rules. 13

The systematic, deterministic workings of these rules may remind you of the orderly on-and-off workings of logic gates. The Ashtadhyayi is, of course, an algorithm, a machine that consumes phonemes and morphemes and produces words and sentences. Panini’s machine — which is sometimes compared to the Turing machine — is also the first known instance of the application of algorithmic thinking to a domain outside of logic and mathematics. The influence of the Ashtadhyayi was and remains immense. In the Sanskrit ecumene, later grammarians suggested some additions and modifications, and other grammars were written before and after Panini’s intervention, but all have been overshadowed by this one “tersest and yet most complete grammar of any language.” 14

The West discovered the Ashtadhyayi during the great flowering of Orientalist research and translation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Ferdinand de Saussure, “the father of structural linguistics,” was a professor of Sanskrit and influenced by Panini and his successor, Bhartrihari; Saussure’s notion of the linguistic “sign” is heavily reminiscent of Bhartrihari’s theory of sphota (explosion, bursting), which tries to account for the production of meaning from linguistic units. 15Leonard Bloomfield — the renowned scholar of structural linguistics whose work determined the direction linguistic science would take through the twentieth century, particularly in America — studied Sanskrit as a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin and later in Germany. As an assistant professor at the University of Illinois, he taught elementary Sanskrit even as he began his own research, “using Paninian methods … and studying Panini.” 16In his own writing, Bloomfield was unstinting in his praise of Panini’s grammar: it was “a linguistic achievement beyond any it [i.e., European scholarship] had known”; it was “one of the greatest monuments of human intelligence” and “an indispensable model for the description of language.” 17He summarized the impact of Panini’s work on modern linguistics as follows:

Читать дальше