“Let’s make it clear to him that we’re not abandoning him,” I remember myself saying, and Osnat had no idea that what bothered me about the arrival of a new caretaker was that he or she might start asking questions about my relationship with Ruchaleh and with Yonatan, both of which had long since strayed beyond the ordinary.

The guest room became my room and I no longer slept up in the attic with Yonatan. After classes at Bezalel, I’d rush home by bus and relieve Osnat, who had started taking sociology classes at the Open University, mostly out of boredom.

“I feel completely unnecessary,” she said, even though, despite the terms of our unwritten agreement whereby I would do all of the hard chores, she continued to do most of the work herself.

As Yonatan’s body began to decay, it became more and more difficult to rotate him on the bed. Putting him on his stomach was never a good idea, certainly not without supervision, and once he was hooked up to the feeding tube it became downright impossible. He could no longer be placed on the special wheelchair for showers and so we began laying out rubber sheets and giving him sponge baths on the bed. Osnat, who had preached the importance of speaking positively around Yonatan and of playing him his favorite music and reading to him from his favorite books, now spoke openly about his dire situation. She stopped greeting him and parting with him each time she came and left the attic and instead spoke only with me, ignoring him entirely. I found her behavior embarrassing and usually after she left I would apologize to Yonatan, sometimes telling him outright and sometimes just letting him know with nothing more than a look.

Aside from the occasional evening when Ruchaleh would have friends over for dinner, the two of us ate together. At first she would come up to the attic and knock on the door and say she didn’t want to eat alone, but later she said she was sick of calling me to dinner like a little kid, and so I would come down on my own, unbidden, at the usual time.

“How’s it going in school?” she asked me over dinner, around a month into my first semester. I nodded in a way that was supposed to imply that everything was under control, even though I was pretty sure I would not be able to finish the semester. I discovered that there was a lot more to school than going to class. All the other students stayed late after class and used the darkrooms and the computer labs, and when I heard that at the end of the semester we were each supposed to present our work, I was sure that I would not make it to that point. Not only did I hardly have time to take pictures, I had no time to develop the film.

“It isn’t easy there, is it?” she said, wiping her mouth with a linen napkin and getting up, motioning for me to follow her.

“Here,” she said, pushing open the door to a small storage room in the basement. “I think the bulb might have burned out but it doesn’t matter. Yonatan used to buy regular bulbs and then color them red.” The light from the hall cut into the darkroom. Ruchaleh pulled a sheet off the top of an enlarger. “I think this thing still works,” she said. “Check it out. If it doesn’t, I’ll call someone to fix it.”

In the mornings, she drove me to school, since we were both going to Mount Scopus. We almost always left the house together. We waited for Osnat to arrive and then we left. If there was time we ate some breakfast at home and when there wasn’t we’d stop somewhere on the way and she’d tuck a fifty-shekel note into my hand and ask me to get two cups of coffee and a couple of croissants. Over time I learned that Ruchaleh did not always have to be on campus at Hebrew University as early as I did, nor did she have to leave as late. “What am I going to do at home?” she asked, and then said, “What, you think I’m a terrible mother?”

No, I did not think she was a terrible mother but I never said anything either way. She was not looking to be comforted, certainly not with words, and I was never sure what effect my words would have, anyway, whether they’d cheer her up or make her snap and accuse me of kissing up to the Jewish boss lady. Slowly I came to be convinced that what she believed was true: that Yonatan’s actions were a form of revenge. He never let up, as though trying to commit suicide each day anew, yet somehow surviving, just like the first time, in order to hurt her, to force her to remember. And ever since I started to use his identity officially, I felt he was doing the same to me, that this man, expiring slowly on his eggshell mattress, was acting rationally, premeditatedly. Sometimes, while we had dinner together or when she came into the darkroom to check out my negatives, during those moments of happiness, I’d feel as though Yonatan might at any minute come through the door, that that hollowed-out frame of a man might suddenly appear at the entrance to the darkroom and glare at us and say, “Just as I always suspected.”

But Yonatan did not get up or glare at us and his situation only worsened. He refused to live and he refused to die. The last time he was admitted to the hospital, around six months ago, was when I called an ambulance after checking his pulse and finding it unusually slow and weak. The ICU ambulance arrived immediately and hooked him up to a life-support machine. I rode with him in the ambulance and Ruchaleh followed in her car. That night a senior doctor who had been summoned to the hospital told us that it was unlikely that he would breathe again on his own.

“Some families, at this stage, decide to. .” he began to say, gingerly, but I cut him off, rejected the notion out of hand. My voice frightened me, the ferocity of it, and especially the notion that Yonatan might just disappear right in the middle of things and leave me all alone.

“I understand,” Ruchaleh said, after I apologized to her for my outburst, tears welling up in my eyes, “but I just can’t go on.”

She hugged me harder than usual and whispered in my ear, “You are going to have to decide.”

NUMBER 624

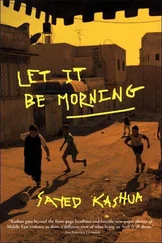

With a shaved head and a five o’clock shadow, wearing a long-sleeved Surfer Rosa T-shirt and green corduroy pants, the camera slung across my chest and round sunglasses on my face; with the old ID card, featuring a sixteen-year-old Yonatan, in my right pocket, and two new photos in my left — that is how I strode, back straight, mustering as much self-confidence as I could, toward the main branch of the Ministry of the Interior in downtown west Jerusalem.

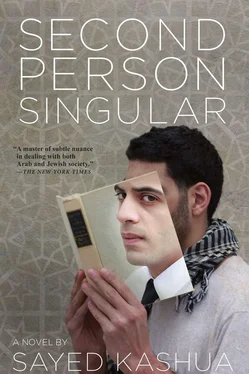

I was in my fourth and final year at Bezalel, one of thirty photography majors. Nothing special. Nothing out of the ordinary. A classic Bezalel student, the kind the school was made for. I was Yonatan Forschmidt: Israeli, white, Ashkenazi, a consumer of Western culture. I was not Sephardic and I was not the token Arab.

Every class needed an Arab. In our freshman year we had the guy from Nazareth, but by our sophomore year he had been accepted at the architecture department and left. In the cafeteria we’d joke that we’d lost our Arab, and one kibbutznik from the Galilee said he’d heard that a class with no Arab was cursed and that we’d never succeed in the Israeli art world without one.

We were saved by the janitor from Silwan. According to the reports in the papers, the guy had been working at Bezalel for five years when the department head discovered him. It turned out that as soon as the guy was done washing the floor and scrubbing the toilets he would head straight for the darkroom, enlarging and developing the pictures he had taken with one of the department’s cameras. Apparently, he had made friends with the photography department’s storekeeper and had access to all the equipment he needed.

The discovery had occurred by accident: the head of the department had come back to the school late one evening and caught the Arab in the act, in his janitorial uniform, in the photo lab. At first the Arab had been terrified and had promised that he would never do it again, but the head of the department looked on in wonder at the drying photos that the Arab had taken in his village. The head of the department had offered him, right then and there, a spot in our class. The Arab said no, legend has it, because he had eight kids to support and couldn’t forgo his salary as a janitor. But the department head arranged it so that the Arab would get a full ride, would start as a sophomore, and would still receive his full salary in exchange for some minor cleanup work in the afternoon. Too bad I wasn’t born an Arab, the kibbutznik said, and everyone around the cafeteria table cracked up.

Читать дальше