The lawyer liked starting his day with a double cappuccino at Oved’s Café but all too often he had to take it to go. Usually he’d find himself sipping his coffee out of a paper cup in his office. On especially busy days, he would very cordially ask Samah to do him a favor and get him some coffee from Oved, adding, of course, that she should get one for herself and whoever else was in the office. But Thursdays were different. They were quiet, practically dead compared to the rest of the week. The lawyer always made sure not to schedule court appearances on Thursdays. If something unforeseen arose, he sent Tarik. The majority of the day was devoted to paperwork.

“Good morning, Mr. Attorney,” Oved said as he brought a brass canister of milk to a steaming spout. “Good morning,” the lawyer responded, looking around the café, making sure he recognized all the faces. He didn’t know them all by name, and he certainly didn’t know them by profession, but Oved’s customers were loyal, and he nodded in their direction. Once he’d gotten some form of recognition in return, he sat down on one of the three bar stools. “For here?” Oved asked from behind the bar. “Yeah, you believe that?” the lawyer responded, nodding, stretching the skin on his forehead and raising his eyebrows.

Oved knew how his regulars took their coffee — how much milk, how many shots of espresso, how much foam, if any, and how much sugar. “You want something with that?” he asked as he began making the lawyer’s coffee. “Yes, thank you,” the lawyer answered, even though he didn’t want anything but coffee at this hour of the morning. Decorum, and the fact that he was occupying a seat in the café, compelled him to show some generosity and so he tacked a pastry onto the bill. “A croissant, please,” he said, nodding.

The lawyer liked Oved and felt that Oved responded in kind. He was the owner of one of the only independent cafés downtown and had also been one of the first people to welcome the lawyer to his new surroundings five years earlier. He was outwardly kind and jovial toward him and somehow the lawyer felt that it was on account of, and not despite, his being an Arab. At first the lawyer thought that Oved was another one of those Kurdish Jews, a Sephardic store owner whose tongue and heart were not in the same place, but soon enough he found that Oved’s political analyses were in line with his own. Occasionally, he even picked up on traces of bigotry that the lawyer had missed. Oved was the last of the socialists in the center of town or, as one of his regulars, an arts editor at a local paper, referred to him, “the one and only communist Kurd in Jerusalem.”

Morning was the café’s busiest time. Most of the customers, like the lawyer, worked in the area, and they took their plastic-lidded coffees with them to the clothing stores, shoe stores, hairdressers, travel agencies, insurance agencies, real estate agencies, law offices, and doctors’ offices. Oved was too busy for conversation with the lawyer, who sipped slowly and looked around often. The skinny journalist was there with a cigarette in her hand and a small computer screen flickering in front of her face. The art history professor, known to the lawyer mostly from his appearances on TV, sat before an open book. The real estate agent sat with a client, speaking loudly about soccer, and an elderly couple shared breakfast without exchanging a word. I wonder what I look like, the lawyer thought to himself as he examined his skewed reflection on the polished chrome coffee machine. Afterward, once again offhandedly, he looked down and checked his shirt and tie.

“Nice tie, Mr. Attorney,” Oved said. “What is it, Versace?”

“Thanks,” the lawyer said, slightly embarrassed. “Not really sure what it is,” even though he knew full well it was Ralph Lauren.

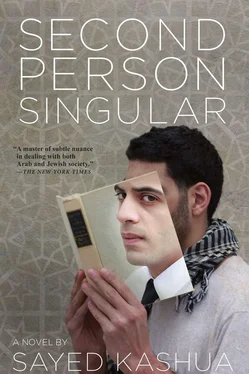

There was once a time when the lawyer knew he looked like an Arab. In fact, it wasn’t that long ago. His first year in university was the toughest of all as far as that was concerned. He was nineteen years old when he left his village in the Triangle and came to the university in Jerusalem. For all intents and purposes it was the first time he had left his parents’ home. He was stopped practically every time he boarded a bus — whenever he left the Mount Scopus dorms and headed toward the Old City, and again upon return. Nothing awful ever happened during those routine checks of his papers but standing there in front of the policeman or the soldier was always annoying, grating, constraining. But unlike other students in those days, who resisted the security checks, refusing to hand over their papers, butting heads with the policemen and the soldiers, charging them with discrimination and racism — assuming their stories were accurate and not mere bravado — the lawyer always forked over his papers with a smile. He was always courteous, wanting the policemen and the soldiers to know that he understood that they were just doing their jobs. The lawyer had always known that he was no hero and that he was not made for clashes, certainly not ones that could be avoided.

As his financial situation improved, he found he was stopped less. During his second year of school he got a job working at the law library and spent most of his paycheck on the kind of clothes the Jewish students wore. After he graduated, during his internship at the public defender’s office, he made a little more money and the security checks grew ever rarer. Then he passed the bar exam, opened his own office, moved to King George Street, and, for the entire five years of working there, had not been stopped once. Not by the police, not by the security guards who worked for the bus company, and not by the border policemen who patrolled the downtown day and night.

By now the lawyer understood that it had nothing to do with the way a person looked, his accent or his mustache. It had taken him some time, but he had finally figured out that the border police, the security guards, and the police officers, all of whom generally hail from the lower socioeconomic classes of Israeli society, will never stop anyone dressed in clothes that seem more expensive than their own.

SUSHI

The lawyer failed to notice how late it was until his wife called. He had been going over his notes as he constructed the defense plea for a member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine who was charged with taking part in the shooting of an Israeli car on one of the Territories’ many bypass roads. The lawyer was fastidious with the details, just as he had been during the trial itself, even though he knew full well, as did the accused and his family, that the man would be sentenced to multiple life sentences and that his only chance of release would be in a prisoner exchange with the Israelis. The lawyer thought these seemingly unwinnable cases were the most interesting. His task, in essence, was to do his utmost to ensure that the verdict allowed his client the chance of being included in a future prisoner exchange. The details — had he seen his victims? Had he hit his target? Had he inflicted the fatal wounds? — would have virtually no bearing on the severity of his client’s sentence but they could prove critical when the Israelis went over the names of the incarcerated and decided, based on the quality and quantity of blood on each prisoner’s hands, who was eligible for inclusion.

The lawyer’s cell phone rang. home appeared on the screen. Only then did he realize that it was seven in the evening.

“Are you still at the office?” his wife asked. He got out of his seat and began packing his bag, telling his wife that no, he had already left.

“Did you swing by Sakura?” she asked, and again the lawyer lied, saying he had placed the order, that they had called to say it was ready, and that he was on his way to pick it up. “Okay,” his wife said. He heard her open and shut the oven door. “We need some white wine, too. You know how Samir is, he’ll get all bent out of shape if we don’t have any. Oh, and did you invite Tarik?” she asked just as he walked out of his office and through Samah’s empty reception area. “Just a second,” he said as knocked on Tarik’s door and opened it without waiting for a response. Tarik was seated at his desk and the lawyer twisted his face and smiled as he spoke with his wife. “What did you say? I didn’t catch that? Did I invite Tarik to come to dinner at our place at eight thirty?” the lawyer said, nodding and looking to Tarik for an answer. Tarik nodded back and the lawyer winked at him and said to his wife, “Of course I invited Tarik. He’s coming. I’ll be home in an hour at the latest. Okay? Bye.” He hung up and put the phone in his pocket. “Sorry, Tarik, I completely forgot we’re having dinner at our house tonight.” Tarik laughed. He seemed to enjoy the lawyer’s absentmindedness.

Читать дальше