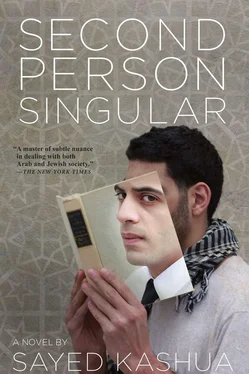

Osnat opened Yonatan’s closet and said, “Let’s see what we can find here for you,” and I was flabbergasted by the sheer volume of clothing. I had never opened that closet before and somehow I had figured that it held nothing but additional sets of pajamas. Instead, there were dozens of ironed, bright-colored shirts on hangers and alongside them a dozen pair of pants. The shelves were covered with stacks of T-shirts, arranged by color, and everything was clean and straight, not a single shirt out of place.

“You’re Yonatan’s size,” Osnat said. “He has so many beautiful clothes. Don’t you, Yonatan?” she continued, looking over toward his bed. “And you don’t mind loaning a few things to our friend here for a date with his girl, do you?” She’s not really my girl, I thought, all she did was invite me to come to the Arab students’ spring semester party. On the other hand, it was going to be the first time I would see her outside work. A part of me was excited by the prospect, but most of me was scared.

Osnat flipped through the shirts and chose a black one with a starched collar. “Black will work well with your pale skin,” she said. “Now, let’s see what else we need. . no, no jeans, I’m sure she’s pretty sick of seeing you in the same jeans every day. . Oh, here, this could work.” She pulled a pair of corduroy pants out of the closet. They were what she called “off-white” and they had a matching jacket with brown leather patches on the elbows.

“Come on,” she said, “try it on. I want to see how it fits.”

“No way!”

“Shut up and change. Go, put it on, I’m in a rush.”

The pants were a perfect fit. They were just right in the waist and length. I tucked the shirt in and put on the jacket. Osnat smiled from ear to ear when I came out in Yonatan’s clothes. She turned me this way and that, walked over to the closet, and returned with a brown leather belt with a wide rectangular buckle. I threaded it through the belt loops of the pants and while I did that, Osnat went back to the closet and pulled out a pair of brown leather shoes. I saw five pairs of dress shoes and three pairs of sneakers. “These are about a thousand times better than your white sneakers,” she said, pointing at the new-looking shoes. She looked me up and down and then pressed the tip of her thumb to the tip of her index finger, drawing a circle with her fingers and announcing, “Perfect.”

“This isn’t me,” I said. I felt like I’d been stuffed into a costume.

“It is totally you. This is what you’re wearing to the party. You look great. There’s no reason for you to put those work clothes back on.” I liked hearing that I looked good. The things Osnat said gave me some hope and for a moment I really did feel like someone else, just what I’d always wanted to be.

“You know,” she said, “it’s not just that you’re the same size as Yonatan. As soon as you came in with Ayub I felt this kind of tightening in my heart, felt at ease with you, as though I’d known you for years and only later did I realize why. You look like him, did you know that? The two of you are practically identical. Don’t you think, Yonatan?” She took her bag, wished me a good shift, and said good-bye to the two of us.

THE SOLES OF OUR SHOES

I got back early from the party. By about ten thirty I was on Scout Street, opening the door to the house and trying to walk on my tiptoes so that Yonatan’s thick-soled leather shoes wouldn’t make any noise. I froze when I saw Ruchaleh out of the corner of my eye. She was sitting in the dining room. Sometimes I forgot she even existed. My heart thumped wildly as I stood there, in an outfit that belonged, in its entirety, to her paralyzed son.

“Good evening,” I managed to say to her, stuck to my spot on the floor. She was sitting at the dining room table, surrounded by folders and papers and an open bottle of liquor. I saw her look me over from top to bottom. She nodded, said nothing, refilled her glass, and went back to her paperwork. I went up the stairs, still trying not to make noise, to Yonatan’s room.

Osnat was sitting on the couch reading a book. She looked at me and then back at her watch.

“What happened?” she whispered. Yonatan was asleep.

“Nothing,” I said. “Everything’s fine.”

“You sure? You don’t look so great.”

“Ruchaleh is downstairs. She saw me in Yonatan’s clothes.”

“So what,” Osnat said. “She doesn’t care. Besides, at this hour, with her drinking, she doesn’t notice a thing. Relax. And if it makes you feel better I’ll talk to her and tell her it was all my idea. Even though it’s totally unnecessary. Believe me. She’s a good person. She understands. Do you know how many years she spent protesting with the Women in Black?”

As soon as Osnat left, I took off the clothes, shoved them into the washing machine, and put on the T-shirt and sweatpants I’d left in the staff closet. I stood in front of Yonatan’s CD collection, which I had begun to enjoy more with each shift, and decided on Lou Reed’s Berlin . I slid the disc in and fast-forwarded to the song about the mother whose kids are taken away, the one that ends with the sound of wailing babies. I flipped Yonatan over on his side so that he was facing me. I lay down on the recliner and listened to the music. Then I took Tolstoy’s The Kreutzer Sonata off the shelf and tried to focus on the text. I didn’t want to remember any part of the party.

Leila had worn a long black dress and a wool jacket, high heels, and just a touch of makeup. The only thing I’d seen before were her hoop earrings, which she’d worn once to the office. She breezed past the guard outside the dorms and smiled at me. I think she was a little bit shy about her outfit, maybe as much as I was about mine.

“Hey.”

“Hey.”

We walked down the road together, toward the club at the Hyatt — it was called the Orient Express — maintaining a safe distance between one another, not saying a word. The only conversation between us was the clack of her heels and the squeak of Yonatan’s leather shoes. Her scent wafted toward me. I looked down, trying to quiet the unrecognizable feelings inside me. What is she feeling right now? I wondered. Does she feel regret, like I do? Why is she not the same easygoing, funny Leila, the rambling Leila I hung out with yesterday in the office?

“Leila,” I said, realizing it was the first time I had said her name aloud. I didn’t even know why I said it, maybe I just wanted to speak her name.

“What?” she asked, turning to me. I shook my head, showing I didn’t really have anything to say, and I looked back down at the sidewalk.

Leila insisted on reimbursing me for the tickets but she let me buy her an orange juice. I got myself a Coke. We were among the first people to arrive at the club. The music of Wadih El Safi played in the background but no one danced. We sat next to each other and still said nothing. Breaking her usual habit, Leila did her best to avoid my gaze. A considerable amount of time passed before she spoke.

“I’m sorry that I’m acting this way, but you have no idea what kind of interrogation my roommate put me through when she heard I was going to the party. She acts like a police officer, watching my every move, listening to everything I say, and reporting back to my parents afterward. She’s disgusting. I can’t stand her. ‘Are you going alone? Who are you going with? Why are you going, anyway? Don’t you have work to do? What are you wearing?’ It’s my first college party, I bought the clothes today. I went to the mall and got the dress. I’m twenty-one years old, can’t I get some clothes and go to a party? Who does she think she is?”

The club started to fill up. Compared to what the students were wearing, I started to feel underdressed. I had never seen this side of campus life. I didn’t know anyone other than my roommates when I went to the university. Leila’s mood improved, she smiled and started talking more. “I just hope my roommate doesn’t come in here looking for me with her hijab, ” she said, laughing. I felt good. The place was crowded and loud and the music started to get more rhythmic. More and more couples moved onto the dance floor. It started with Shadi Jamil, classic high-country stuff, then Sabah Fakhri, and from there to some very danceable Egyptian pop. It was obvious to me that Leila wanted to dance. She was moving to the music and singing along. I didn’t recognize most of the songs, which surprised Leila. “What, you don’t know who Amr Diyab is?” she asked.

Читать дальше