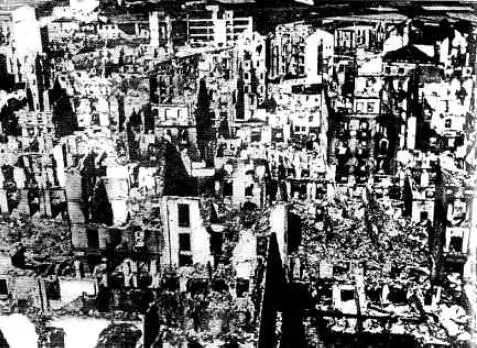

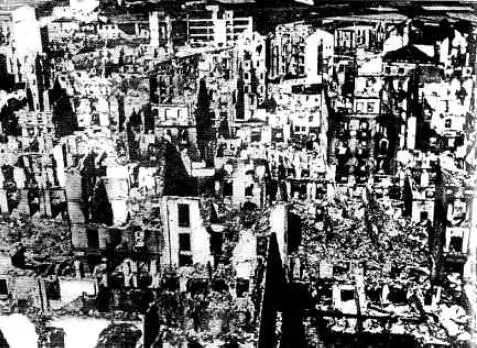

Toledo itself was lousy with tourists despite the fact that it was winter. We dodged and mocked them as we ascended the narrow streets toward the giant Alcázar, a stone fortification built on the city’s highest point, which Isabel assumed I would find of particular interest because of its famous role in the Civil War, or at least its role in Nationalist lore: a bunch of fascists held out against the Popular Front, which laid siege to it, until Franco arrived with the Army of Africa, an early and highly symbolic victory for the Nationalist cause. As we walked around the giant structure, which had to be largely rebuilt after the war, she recounted facts I barely followed about historical figures of whom I’d never heard. Then she began to ask me questions about my project, which had never interested her before.

“How did you choose Spain over, for example, Chile?”

“So much has been written about Allende,” I said, although I had only the vaguest sense of who Allende was.

“What makes the poem an effective form for a historical investigation?” I inferred from the words of hers I understood. I was surprised to find myself inclined to defend a project I’d never clearly delineated, let alone ever planned to complete, as opposed to conceding its total vacuity.

“The language of poetry is the exact opposite of the language of mass media,” I said, meaninglessly.

“But why are Americans studying Franco,” she asked, gesturing toward a group of Americans being led around the Alcázar, “instead of studying Bush?” She said it as if every American tourist were planning a monograph on El Caudillo.

“The proper names of leaders are distractions from concrete economic modes.” I was trying to sound deep, hoping concrete and mode were cognates. My limited stock of verbs encouraged general pronouncements.

“Why aren’t you studying the American economic mode?” She was angry.

“You can’t study a mode of production directly.” And with my manner, I said, “I am delivering a fact so obvious it pains me.”

“I’m sure the people of Iraq are looking forward to your poem about Franco and his economy.” It was the first unkind thing she’d ever said to me.

I met this with silence, so as to allow her to imagine an array of responses I was in fact incapable of producing, and I held this silence as we left the Alcázar and descended back into town toward the cathedral, where there were some famous El Grecos, although if I never saw his torturously elongated figures or phantasmagorical, sickly coloring again, it would have been too soon. What disturbed me as we walked was not that Isabel was pissed off, and certainly not that she thought my project was absurd or that she found me to be a typically pretentious American, but that our exchange, despite my best efforts, and perhaps for the first time, had involved much more of the actual than the virtual. I’d said, as usual, nothing of substance, but the nothing I’d said just languished between us; I didn’t feel her opening it up into a chorus of possibilities, and the silence we were now maintaining was the mere absence of sound, not the swelling of potential meanings. This was in part because my Spanish was getting better, despite myself, and I experienced, with the force of revelation, an obvious realization: our relationship largely depended upon my never becoming fluent, on my having an excuse to speak in enigmatic fragments or koans, and while I had no fear of mastering Spanish, I wondered, as we walked past the convents and gift shops, how long I could remain in Madrid without crossing whatever invisible threshold of proficiency would render me devoid of interest.

It was early dusk by the time we reached the cathedral, and in a Spanish cathedral it always felt like dusk, dull gold and gray stone and indeterminate distances, so I had the feeling less of going indoors than of entering a differently structured but nonetheless exterior space. I was alarmed to find myself wanting to produce an elegant formulation of this experience for Isabel, alarmed not only because I couldn’t formulate anything elegantly in Spanish, but because this was the first time in her company that I had desired to get my point across instead of attempting to make its depth a felt effect of its incommunicability. Now I feared I’d neither be able to be eloquent positively nor negatively and, as we made the rounds of the capillas, I realized with a sinking feeling that the reduction of our interactions to the literal and the transformation of our pregnant silences into dead air, a flat spectrum over a defined band, would necessarily strip my body of whatever suggestive power it had previously enjoyed, and that, when we made love, she would no longer experience her own capacity for experience, but merely my body in all its unfortunate actuality.

I tried hard to imagine my poems or any poems as machines

that could make things happen.

I could feel the initial creep of panic, and as I reached around in my bag for a yellow tranquilizer, I encountered one of my notebooks, which I took out; I found a pen and quickly jotted down the idea about the dusk and the cathedral, aware and encouraged that Isabel was watching as I wrote. I arranged my face into a look of intense concentration, a look that implied I’d had a lightning flash of intellection, that there was no time to waste on speech as I hurried to give my insight a more enduring form. Isabel broke our silence, maybe half an hour old, to ask what I was writing, and I said I’d had an idea for a poem, possibly an essay. She waited for me to elaborate, which I didn’t, and I believed she looked with real curiosity at my notebook as I returned it to my bag. This, I thought to myself, as we finished our circuit around the cathedral and emerged into the darkling street, would allow me to retain my negative capability, although that wasn’t the phrase; I could displace the mystery of my speech onto my writing, the latter perhaps recharging the former. If our conversations were no longer shot through with possibility, if what I said no longer resonated on many potential levels simultaneously, what I wrote in a language she could not read would have to preserve my aura of profundity. And since the raw material for these notes that were the raw material for poems emerged out of our time together, she would in some important if unnamable sense have a hand in their genesis; there would be traces of her presence, she might imagine, in subject or formal process. Indeed, if the poems did not prove powerful, maybe she shared in the responsibility, as it would mean, if she had faith in my talent, that our time together failed to inspire me, and why wouldn’t she have faith in my talent, given that I’d attended a prestigious university and received a prestigious fellowship. She would experience the present as suffused with the possibility of eventual transfiguration into a poem, and this future poem was a fund each moment could draw upon; my notebook, not my fragmentary Spanish, would become the sign of the virtual, enabling my project to advance. I was so calmed and encouraged by this new narrative, I forgot about the tranquilizer, and as we walked toward the ramparts near where Isabel had parked, I said to her:

“I read my poems and a friend read translations at a gallery in Salamanca the other night.” This was intended to hurt her a little and it seemed to. Since I’d never planned to read, I’d never thought to invite her, and besides, I had a policy of keeping Isabel away from Arturo and Teresa, not because I didn’t think they’d like each other, but because I wanted them to believe I had an expansive social life. But I knew she would be stung to think I’d given a public performance without her, stung and impressed I was receiving such attention, and that all of this would improve her image of my poetry, lend it mystery, while also making her jealous of my other friends.

Читать дальше