She had remained unmarried for Professor Dai, Siyu thought now, and she would, with her blessing, become a married woman. She would not wish for her husband’s death, as his mother had, because the marriage, arranged as it was, would still be a love marriage. Siyu had wished to be a companion for Professor Dai in her old age, and her wish would now be granted, an unexpected gift from a stingy life.

“So this is an engagement dinner, then?” Hanfeng said, feeling that it was his duty to say something to avoid silence among the three of them. He doubted that he would feel any deficiency in his life without a wife, he had said the night before, and his mother had replied that Siyu was not the kind of woman who would take much away from him.

“We don’t need any formality among us,” Professor Dai said now, and told Siyu that she should move in at her earliest convenience instead of wasting money on rent. Siyu looked down the hallway, knowing that the room which served as a piano studio for Professor Dai would be converted into the third bedroom, the piano relocated to the living room. She could see herself standing by the window and listening to Hanfeng and Professor Dai play four-hand, and she could see the day when she would replace Professor Dai on the piano bench, her husband patient with her inexperienced fingers. They were half orphans, and beyond that there was the love for his mother that they could share with no one else, he as a son who had once left but had now returned, she who had not left and would never leave. They were lonely and sad people, all three of them, and they would not make one another less sad, but they could, with great care, make a world that would accommodate their loneliness.

As always, I am deeply grateful to:

Sarah Chalfant and Jin Auh, for taking extraordinary care of my work; Kate Medina and Nicholas Pearson, for their continuing support; Cressida Leyshon, for the many great discussions about stories.

Amy Leach and Aviya Kushner, for being indefatigable friends.

Dapeng, Vincent, and James, for their love.

Mr. William Trevor, for his generosity and kindness.

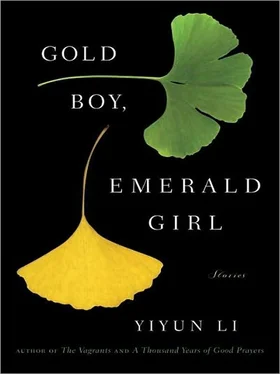

YIYUN LI is the author of A Thousand Years of Good Prayers and The Vagrants . A native of Beijing and a graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, she is the recipient of the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, the Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award, the Whiting Writers’ Award, and the Guardian First Book Award. In 2007, Granta named her one of the best American novelists under thirty-five. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, A Public Space, The Best American Short Stories, The O. Henry Prize Stories , and elsewhere. She teaches writing at the University of California, Davis, and lives in Oakland, California, with her husband and their two sons.

Reading Group Questions and Discussion Topics for Gold Boy, Emerald Girl

It seems that none of the stories from the collection can straightforwardly be called a happy story, yet happiness is never far from the characters’ minds. For instance, in “Kindness,” Moyan describes her happiness looking at trees, saying: “I loved trees more than I loved people; I still do.” In “Souvenir,” the unnamed young woman believes that she was happiest when she sat with a young man who had gone crazy from torture, because she could be like a piece of harmless furniture to him. What are other instances of happiness for the characters in this collection? What have the characters given up to achieve their happiness, and what do these compromises reveal about the characters and the time they live in?

Every one of the stories in the collection has a love story, or several love stories, in it. What are the moments in these stories when love transcends the bleakness and “fatality of humankind,” as the young woman in “Souvenir” calls it at the end of the story?

Many of the stories are set in China at a time when the modern world clashes with traditions, creating situations that baffle the characters and change their lives in one way or another. For instance, in “The Proprietress,” a young woman finds herself the object of a great deal of media attention when she petitions to have a baby with her husband, who is on death row. What are some other situations that you find especially fascinating or perplexing in these stories? Do you think these situations are particular to life in China, or are they more universal?

The beauty of human memory is that, in any given moment, each of us is living multiple lives, anchored in different time periods — our decisions and perceptions about our lives reflect not only the present moment but also what has been carried on in our memories. History, especially Chinese history in the past fifty years, has given Li’s characters richly layered memories. Which of their memories moved you most, and why?

Many of the stories feature older characters — an old woman unwilling to give her son and daughter-in-law control of her life in “The Proprietress”; Teacher Fei, the retired art teacher, and his mother in “A Man Like Him”; the six friends who establish a business to fight against extramarital affairs in “House Fire.” What do you think Li, a writer in her thirties, has done to make these characters believable? What makes their stories important and compelling?

Many of the stories are set in China, which, in the past thirty years, has transformed itself with dazzling speed. Yet in any society, during any given period, human nature evolves at a much slower pace. What are some of the beauties and follies of human nature that you have seen in the characters that seem to have remained unchanged, despite the surface excitement of a new country and a new millennium?

The centerpiece of the collection is the novella “Kindness.” What sorts of kindness and unkindness are present in the novella? And in the other stories? How do the characters in these stories come to term with the kindness and unkindness of their fates?

Despite the major and minor tragedies many of these characters have to live with, there are moments in each story when a character allows him- or herself to envision a future that is at least a little better than the past, or the present. In “Number Three, Garden Road,” the two neighbors allow themselves to be “happily occupied” in the falling dusk by the music of an old banjo; the title story, “Gold Boy, Emerald Girl,” ends with Siyu’s thought that “they were lonely and sad people, all three of them, and they would not make one another less sad, but they could, with great care, make a world that would accommodate their loneliness.” What are other instances when the characters, despite the harshness or bleakness of their lives, do not lose their ability to imagine a better future?

Li grew up in China, and English is not her first language. Is there anything about her writing that would indicate this to you, if you didn’t know already? What do you think makes her writing stand out, as a writer in a second language?

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу