“The floor is filled with fish, babe," the woman says to the man, who reclines on his back with his arm across his eyes.

“What kind`?"

“Redhorse suckers."

“Hmm. Had me two bluegills at wunst on my onliest hook, saw a yellertail, din’t see no carp.” The man is doing put-on talk too. The carp are delighted with these people, their hosts. The carp flow out of the room by the drain of the window, leaving the floor cleaner than it was before their tour. When they are back in the river, the river is kinder to them. All day they say, Wunst we went to a room, and the river says, Sure you did, boys.

Bream Bedding

— I smell fish. You smell fish?

— Smell like… no.

— Like bream beddin! That a smell now, people say you cain smell no fish under water but you sure as—

— We know that, Erasmus. Save it for the tourists.

— Ain no tourist.

— We know that too. What we do not know is why not. The Negro woman can hold a fond court among her handicrafts upon the roadside, or wrap her head and sell pancakes or God

knows what else, baskets, you name it, and be blinded by flash-bulbs. But I have yet to see a council of elders such as ourselves holding court on the courthouse lawn all the live-long day, as we do, with so much as one person interested in us at all.

— Cept if he don’t know what state he in.

— Exception duly noted. Short of that, the white man has no use for us. Why is this?

— Is we got any use for us?

— Erasmus, that is entirely beside the point, existentially speaking.

— Well scuse the doowop out of me. I smell fish, an I tell you something: they come out that winder up there bout a half-hour ago, a funk parade to beat the band.

— You saw them — what, fish po out that window?

— Shet up wid yo po. No, Satohmo, they disnt not po out, I disnt not eben see em, I done smelt em, as I told you in a straightforward reportorial manner innocent of shuck, jive, prevaricate, and procrastinate. If you were not so concerned with the want of a gaggle of tourists who you somehow fantasize could be interested in us and the anachronistic reminder of the pox on their land that we represent, you would perhaps be in a position to listen to someone. When, ah mean, he speak to you. Bout something impotent.

— Fish.

— Right on. Come out dat winder up yonder. Girl up in deah too, lookin good.

— With Mr. Whatstate?

— Yessiree. You tell me, existentially speaking, how a man don’t know what state he in get a woman like that in his bed — you tell me that, existentially speaking, you be tellin me something.

Differently Different

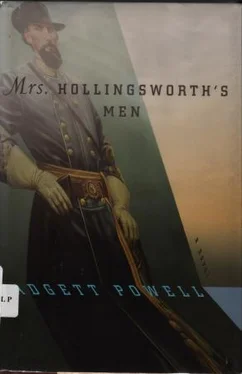

You could get cigars and even guys at the grocery store, though not by fiat, Mrs. Hollingsworth reflected, but you could not get carp, or bluegill, or bream. She was getting stranger in her shopping wants. She was getting further from what was available. The meal she was assembling was going to satisfy only a hungrier, larger fool than the kind of fool she had originally thought she might invite to dinner.

This getting stranger did not bother her. It had been coming on for some time. She had felt restless, of course, in specific and vague ways, all her life, as have, she figured, all people paying sufficient attention to their lives to admit that their lives are utter mysteries. But lately there had been an agreeable yawning in her heart, a surmising of new hollow She was trying to draw a breath of something with nothing visible or prudent in it, just other air. When she breathed this air, or tried to, or pretended to, or merely hoped to, she fancied that she was trying to breathe an air that no one near her cared or knew anything about. Her daughters, for example: they had makeup, men, ambition or not, they were fatigued or not, with the world or with her or not. Her husband was. . well, himself. Men did not entertain the vapors, or if they did, which she allowed might happen, they went off the edge entire and wound up in institutions of either a gentle or a cruel kind. But there was a safe zone for women to lose their minds and remain among the zombies who had not, and to not be recognized as having lost their minds. The zombies, after all, were pretty slow to appreciate someone other than themselves, and they had been schooled not to denigrate the different. They were attending just now, in fact, a large adult-education academy, studying a curriculum that insisted there was no such thing as difference at all. The harbinger for this had been, she supposed, handicapped-person legislation. It had come from somewhere, and it had received a great activating boost of philosophically underpinning energy from the American academy, which had invented political correctness, a new language, to shore up the shaky proposition that there were no differences among people. Mrs. Hollingsworth discovered this when she went to the local university to take a night course in Coleridge and found instead, in the scheduled room at the scheduled time, a course entitled “Theorizing Diaspora, Adjudicating Hybridity."

On the blackboard, on a paper handout, and on individual CRT screens in front of each seat in the room was a statement:

The primary requirements are a strong commitment to visually expressing support for all students within our community. By displaying the provided sign or button, a Friend can send a message of acceptance or encouragement.

We encourage proposals on the rhetorical intersections of gender with race, class, age, sexuality, and ability; interpreting the academy, disciplinarity, and professional identities from a feminist perspective; reclaiming the lost or marginalized voices of women (e.g., rhetors, writers, teachers, artists, workers); analyzing the rhetoric of historical depictions of women; the rhetoric of the feminist movement and the feminist backlash; males and mens studies and scholarship in relation to feminism; extrapolations of theory from the everyday (e.g., etiquette manuals, cookbooks, diaries)

Mrs. Hollingsworth was dazed by this, but snapped to at “cookbooks”: was she perhaps, she wondered, already extrapolating theory from a grocery list? Maybe she had finally written her paper for the course, if she could induce the professor to include grocery lists in the catalogue of extrapolatable genres. That odd phrase rolled in her brain a moment until she became aware that there was a man in sandals and socks speaking very softly and very self-assuredly at the head of the long table that they — she and some much younger students — were sitting at. He was saying, ".. the interactions of discourse and ideology — that is, how the work of the poet operates within a variety of prevalent romantic cultural discourses — e.g., romantic, amatory religious, hedonist, colonialist — in order to collaborate with, challenge, oppose, or, in rare cases, subvert them." Here, at “subvert,” the professor raised his eyebrows several times until everyone at the table chuckled, which it seemed to Mrs. Hollingsworth was the actual requirement so far of the course. She had failed to chuckle. At the same moment that she perceived everyone in the room to be staring at her very politely, she noticed in her hand a button of the pin — on political variety that said on it FRIEND.

Into the silence that apparently awaited something from her, Mrs. Hollingsworth said, “Are we going to read ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”P”

“You mean theorize diaspora, adjudicate hybridity?” the professor asked, with more of the eyebrow hydraulics.

She could not respond, so the professor, whose role seemed to be that of helping out the obtuse, went on: “We will focus on the ways in which diasporan subjectivity complicates and problematizes the relationship between theory and identity, on the one hand, and representation and collectivity, on the other.”

Читать дальше