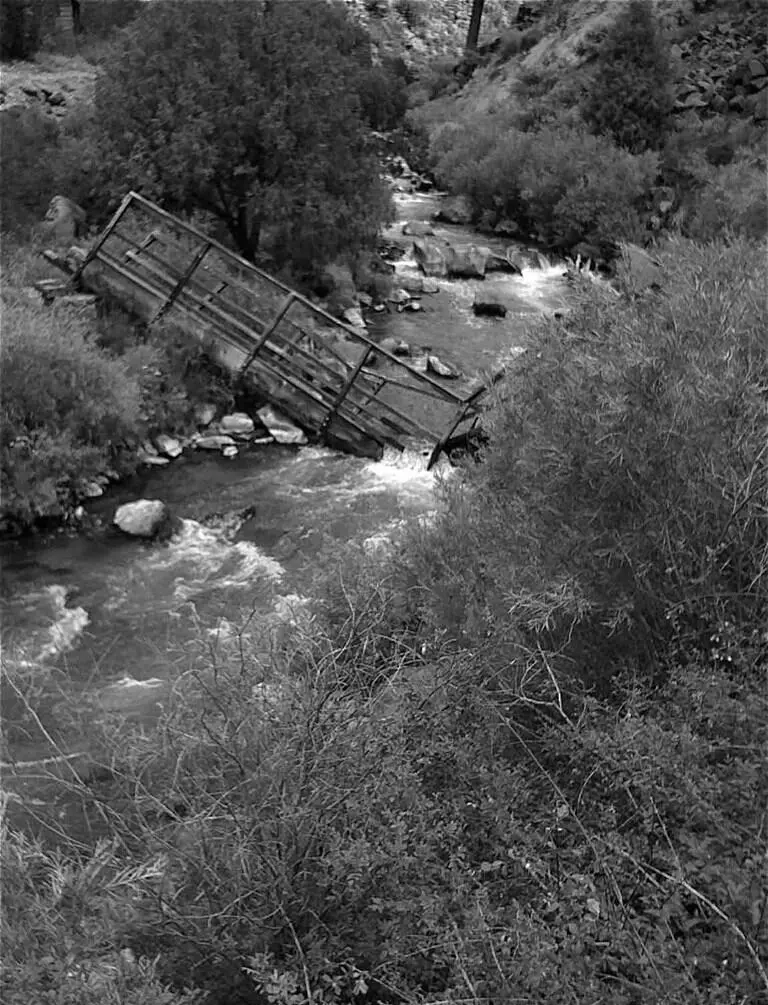

I ran. In the milky faces I saw the soldiers of My Lai, wide-eyed violent lust-burning gazes, their mouths agape and gap toothed, their voice high registered and pig-squealing with perverted delight, hardly animal but all too certainly human. I ran and I ran along that dirt and gravel lane but turned off, afraid that I would be too easily seen in the twilight, the unfolding moonlit night, my white high-top Converse sneakers promising to give me away. So I cut into the inky woods where I made much noise breaking sticks and brush and being slapped by low branches, but my noise was so much less than their beastly moaning that it hardly mattered. I could see my father’s expressionless face telling me to run. I wasn’t sure I was being chased, to this day I do not know if those red legs, those rednecked inbred bastards, actually chased me into the night. I remember the hooting of owls, especially when I came to a broken-down footbridge, the water racing over its collapsed middle. I used the structure to support myself as I splashed through the chilly water.

I made my way up a steep embankment to the shadowy blacktop, a stretching, sable ribbon twisting through the darkness, and I ran, not choosing a direction; the direction chose me. A pickup truck caught me in its yellowed headlights and skidded to a stop. I was too tired to run any farther and so remained there, bathed in the sick glow, my hands trembling on my soaked denim knees, my chest heaving. It was not until I saw that the driver was a black man that I started quietly crying, for so many reasons. He approached me cautiously, turned sideways like a crab. I tried hard to say something but could not make a sound. He told me to slow down, called me son and I didn’t like that, tried to put a hand on my back. I moved away from his touch. I told him that they were going to kill my father, that they were killing him. I said KKK and he scooped me up in his arms, shoved me into the cab of his truck, and drove off in the opposite direction. I recall that the cab of that truck stank of turpentine and that there was no door on the glove compartment.

The stories we could have told. Give me your evidence. Shant, said the cook. And here we are, supine, what a lovely word, like the name of a flower, look at the supines in the meadow, a sad vision actual, a virtual vegetable garden, and we cucumbers among them, in our proper rows. You can be Murphy this time. I’ll be you.

Do you see what I see? Turn about and wheel about, and do just so. But all that disappears into the water that is behind us and in the desert that lies ahead. None of what mattered matters and it will not matter if the matter matters, no matter what, as a matter of fact. A lie we would do well to believe. But here I am, me again, head propped up, sort of, at a seventeen-degree angle, the bright overhead lights offering no bother. I could be writing you could be writing me could be writing you. I am a comatose old man writing here now and again what my dead or living son might write if he wrote or I am a dead or living son writing what my dying father might write for me to have written. I am a performative utterance. I carry the illocutionary ax. But imagine anyway that it is as simple as this: I lay dying. My skin used to be darker. Now, I am sallow, wan, icteric. I am not quite bloodless, but that is coming. I can hear the whistle on the tracks. I can also hear screaming, but it is no one I know. So, fuck them.

First Continuation

In some woods you became lost, the darkness swallowed you and then spat you out in a quiet place at dawn, where you sat crosslegged beside a tree that in stories might have been called stalwart or majestic, and you sat in a crook of that massive trunk, whereupon you were approached by a young woman who saw and attended to the wounds on your arms from the brush and thicket, dabbed at your blood with broad leaves from a nearby shrub. She wouldn’t look directly at, but stole peeks at, your eyes and you were pleased she was there but more confused, her tender touch slowing your breathing, relaxing your neck. She felt immediately like a friend, steady, redoubtable, like the oak against which you leaned. You wanted to say something, to tell her why you had been running, to ask her how you had come to be in this place, to ask just who she was, but every time you tried to speak kaks and clucks came out and spittle rolled down your chin. The girl finally looked at you and she said, Take care of the sense and the sounds will take care of themselves. Her words were familiar and had the ring of truth, looked true on her lips.

They killed my father, you said.

She nodded sadly. And yet here you are.

And where is that?

Where is what?

Where is here?

It’s here.

You sat up straighter and imagined that you understood. What is here next to?

There.

And how far is it from here to there?

Once you leave here, you’ll be there. You’re silly. Next you’ll no doubt want to know how long it takes to get there. Well, I can tell, it varies. If you look over there you’ll see that it’s here for as far as you can see. Do you hear that?

What?

It’s the bear. He’s here.

Where?

Over there.

How can he be here and there?

Oh, here and there are not so different. The two are so much more alike than then and now or now and again, but not near as similar as how and why.

How and why? How are they alike?

Why do you ask?

Because you just said that how is like why.

No, I said they are similar.

I know.

You’re not suggesting that similar and alike are the same thing, are you? Why, they couldn’t be more different.

How are they different?

I don’t know. You tell me. I just know that they couldn’t be more different. They can’t, can they?

I need to find my father.

I thought you said they killed him, whoever they is.

The klansmen killed him.

Whoever they are, she said. Back to how and why? You will later ask yourself how you survived and you will wonder why you survived. So you see, one is the other and vice versa.

I don’t care about all that. You pushed yourself to your feet and brushed off your clothes, then paused to wonder why you’d bothered. I have to be going, you said. I don’t like it here. All you speak is nonsense.

Of course, that’s true, and wouldn’t it be sad if I didn’t? Of course I do and I rhyme, too, but I could make not a sound if it weren’t for you.

I’m sad about my father.

You miss him.

Yes.

But imagine if you didn’t.

What do you mean?

Imagine what it would mean if you didn’t feel so bad, if he were dead and you didn’t feel a thing or you felt good.

That’s not possible.

It’s not possible only because it isn’t, but it is very possible because it could be and since it could be, try to imagine what it would mean. When children die they come back as themselves as adults.

What about when adults die?

A riddle, a riddle, violin or fiddle.

Who are you? you asked.

I am a little girl.

What’s your name?

My name is Name. My name is my name and the name of both the word name and Name, my name. I am not the only one with the name Name and also there are other names.

I’m getting out of here.

Читать дальше