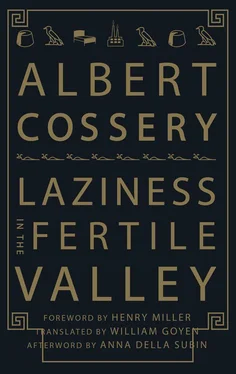

Albert Cossery - Laziness in the Fertile Valley

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Albert Cossery - Laziness in the Fertile Valley» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: New Directions Publishing Corporation, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Laziness in the Fertile Valley

- Автор:

- Издательство:New Directions Publishing Corporation

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Laziness in the Fertile Valley: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Laziness in the Fertile Valley»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Laziness in the Fertile Valley — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Laziness in the Fertile Valley», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“I can’t come with you,” said the child. “I have to go on hunting.” He hesitated a moment. “But if you’ll give me a half piastre, I’ll come. I haven’t a house to eat in. You understand!”

Serag fumbled in his pockets, drew out a collection of junk, among which was a two milliemes piece. It was a souvenir he had kept for a long time. Suddenly he had remembered it.

“I haven’t much money with me right now,” he said to the child, holding the coin out to him, “but here are two milliemes. Will that do?”

“We won’t haggle,’ said the child. “It’s all right, let’s go!”

II

The path they followed was hidden by the corn field. The child walked ahead — limping, either because of his injured foot, or only to give himself the air of an heroic martyr. Ever since he had touched his two coins he had abandoned himself, overflowing with unbelievable energy. He had torn off an ear of corn, crunched the hard kernels, then spat them on the ground with disgust. Serag paid no attention to him. He felt only his presence, and his gesticulating walk kept him from sleep. He moved forward like a sleepwalker, his brain invaded by thick clouds.

For a moment the cold became very sharp. Serag shivered at each blast of wind. His red woollen sweater, with its rolled up collar, scarcely protected him. But this seemed only a minor evil. He was really oppressed by his shoes. As always, when he went out to look at the factory, he wore his old football shoes, a survival from his years at school, and they weighted down his steps and bruised his feet. No mere whim governed his choice of this strange gear; it had a profound meaning for him. Serag wished to prove to himself, in venturing on this pilgrimage, that he was making a dangerous expedition. The idea of performing some daring feat filled him with a certain fervor. Without this fervor he wouldn’t have had the courage to try anything. Therefore, he suffered the football shoes, as a torment necessary to his liberation.

Suddenly the path grew wider, and they found themselves in the middle of a field planted in clover. A peasant’s hut of dried mud, partly in ruins, stood on the edge of an ancient trench filled with weeds. Nearby, a dismantled sakieh lay in the dust. Serag stopped; he could go no farther. He stumbled down the side of a furrow and dissolved in tears.

The child continued on alone for several steps, then turned and came back toward Serag.

“You paid me to come with you. Let’s keep going.”

“I’m tired,” implored Serag. “Have pity on me.”

“You’re crying,” the child observed, puzzled. “Why? Are you sick?”

“It’s nothing. I’m not sick. I’m just tired. Give me one more minute.”

“I can’t wait,” said the child. “Stop crying. What a day this is! There probably isn’t any factory at all.”

“There is a factory,” said Serag. “On my honor, you’ll see it soon. We aren’t very far now.”

“Why do you want to go there?”

“I’ll explain in a little while. You’ll see. It’s very interesting.”

The child pondered a long time. What drew this sleepy young man to see a factory? After puzzling awhile he seemed to have found out.

“Tell me: you’re not looking for treasure by any chance?”

“No, it isn’t treasure,” said Serag. “It’s only a factory under construction. Believe me, there isn’t any treasure.”

“It doesn’t matter,” said the child. “Maybe we can find some treasure anyway. Now get up! I’ve waited long enough. This day’s wasted for me.”

Serag got up painfully, ran his fingers through his hair, then searched the horizon as if trying to orient himself. A pile of twigs burned somewhere behind the high stalks of corn. In the distance, some crows fled under the low clouds. Serag recognized the place, put his hand on the child’s shoulder and prepared to take up his march again.

They didn’t walk long. Coming to the end of the field, they turned left, crossed a dry pond, then climbed a little hillock.

“Here’s the factory,” said Serag.

In a large stretch of land, lying fallow like wild country, the unfinished factory lay in the middle of a mass of rubbish and crumbling scaffolds. It was a strange and awful place, uneven with quagmires, forbidding. It seemed more like a wrecking yard. There were only the fronts of walls, half constructed — a whole derelict architecture partially completed, abandoned to the briars. All around fragments of old iron and rough stone were lying in the dirt. In a corner at the far end of the field were piles of corrugated iron, covered with a heavy layer of rust. Work seemed to have been stopped a long time; it was already more than six months since Serag had seen anyone there. He couldn’t understand the reason for this. Two or three times a week he came here to take a look, in the hope of seeing the masons resume their work. But it was always the same deception. The factory remained as it was, giving the impression of a phantom or a stage set.

The child had lost his mocking exuberance. He seemed dismayed, in the grip of some pitiful fear. It was apparent that he’d forgotten the treasure.

“Is that the factory?” he asked.

“Yes,” replied Serag. “I wonder why they don’t finish it. I’d like to work there.”

“What kind of factory is it?”

“I think it’s for textiles. I want to apply for a job.”

“And if they don’t finish it?”

“Then I’ll never be able to work,” said Serag wearily.

“Why, are you out of work now?”

“Well, you see, I’ve never worked yet. But I’m very anxious to begin.”

“You’re crazy,” said the child. “You want to work in a factory! What a day for your mother!”

“Listen, little one! I want to work; I think I’ll be able to do a lot of things.”

“What can you do?”

“I don’t know yet. But a man has to work, don’t you think?”

“You’ve got a house where you can eat and you want to work! What a joke.”

They stood for a few minutes without speaking.

“Why don’t you look for a job in the city if you want to work so much?” the child began. “Because if you ask me, this factory would make a good latrine.”

“I can’t go to the city,” said Serag. “It’s too far. The good thing about this factory, you see, is that it’s so close to our house. I won’t get too tired coming here.”

“You get tired very fast. Are you sick?”

Serag didn’t answer. The nearness of the factory was an excuse he clung to in despair. In his heart, he knew the factory would never be finished and, because of this, he would never run any risk of working there. When he faced this deceit, Serag despised himself. He was unhappy and made endless reproaches to himself. Then, to justify himself, he would say it was only a beginning but that what he had already done was a satisfactory start. The courage it had taken to make this pilgrimage, to look at the place where he ought to have worked, was already enough to merit esteem and confidence. He gave a last look at the unfinished factory, fortified himself with the idea that he was already on the road of social progress, and congratulated himself inwardly.

The sky continued to drift its malevolent clouds into remnants. A heartbreaking and secret melancholy crept into the folds of the landscape, invading the country like the approach of evening. Near the unfinished factory, a starving dog wandered among the rubbish. It sniffed everywhere, without insistence, as if it had already lost all hope, then vanished behind a wall. Serag waited to see it reappear, then turned towards the child. He was behaving wildly again, shooting in the air with his slingshot, without concern for a target, simply for the pleasure of moving. He seemed no longer interested in Serag; and he had returned to his vagabonding life. Suddenly he stopped and asked, as if disturbed:

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Laziness in the Fertile Valley»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Laziness in the Fertile Valley» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Laziness in the Fertile Valley» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.