“You’d best not cross Pinky,” said Henry, the bull-cook, her husband, as I was leaving the dining room. He was a large, muscular man who sliced, chopped, diced, peeled, ground for her, and kept her big wood stove stoked. His strong back was bent and stooped as if subservience to his wife was a kind of scoliosis.

That night I was shocked into wakefulness by a sharp pain on the crown of my head, as if Pinky had struck again. I snapped upright and looked to the window across the room that glowed strangely. I put out a hand to touch Jingle, forgetting she was in the women’s bunkhouse. All my other bunkmates were asleep. I was drawn to the window. I had never been this deep in any Idaho before. As I got closer I could see the face. Big cat stared at me. The eyes aimed bolts of lightning at my heart. “Less talking, more eating.” The windowpanes buzzed with the sound. It was Pinky at the window. Jaguar at the window. In my usual foolhardy way I rushed to the door and threw it open, because I wanted to see all of this big cat. The stars expanded above, around me, pulling me apart in their clamor. “Best not cross Pinky,” they chorused. I remembered to breathe. I had never been so enfeebled, so emboldened, so smothered in stars.

I was hired to teach at The University of Notre Dame, in South Bend, Indiana. I half believed the maxim that “them that teach don’t do,” so I was leery of teaching. I’ve always been committed to doing. I never liked school as an institution, felt individual creative paralysis was attached to any institution. But with kids in college, I needed a steady income. This was the possibility of a salary, with the most free time for writing. I’ve been pretty good at teaching most of the time, and never really regretted the move, but occasionally it has felt itchy, like living in an alien skin.

That was a confusing time for me. My marriage was breaking up. I was pulling out of my family. I was dizzy with remorse and guilt. I staggered into the little Datsun pick-up out of our family home in Pine Bush, New York, and drove for South Bend, feeling like a fighter who has been blasted for seven rounds, punchy, knocked down several times, with no choice but to keep going.

Just like the Vatican within Rome, Notre Dame is an independent entity within South Bend. Notre Dame, Indiana, is its own Post Office. South Bend had been the home of Studebaker. Notre Dame was home of The Four Horsemen, and Knute Rockne. I pulled into the town feeling like I’d taken a right hook that put me down into flatland Midwest. I had no idea where I was. I managed to find my way to a diner and grabbed a burger and some coffee. The diner owner noticed my New York plates, and asked me what I was doing in South Bend. I told him I was about to start teaching at Notre Dame. “You’d better like football,” he said. “If you don’t like football, you might as well leave South Bend.” I liked football okay. Now I knew where I was.

One of my colleagues advised me to buy season tickets at the faculty price. I wouldn’t regret it. My seat was behind the end zone, at the “Touchdown Jesus” end of the field. Behind me was the famous mosaic on the Hesburgh library — the huge savior faced the football end zone with both arms raised. On either side of me sat a nun with a season ticket. Each had a canister of compressed air attached to an air horn. Every time there was some Fighting Irish excitement they would blast them in my ears. I knew my hearing couldn’t survive many games. I suddenly dreaded the entertainment of Saturday football. I discovered I could scalp my tickets in the stadium parking lot before each game. Many of my colleagues were out there hawking tickets with me. That was the gist of the advice I got to buy the season tickets. It was a way to supplement a modest salary.

A carefully detailed body of Christ hangs from each cross inside the door of each classroom at Notre Dame. This is a well-built savior, six-pack abs, pecs of a halfback, a white man’s face. Although I rarely give it a thought, as I entered the classroom I did think to myself, “I’m a Jewish guy.” I remember my uncle Sammy always saying, “You don’t have to worry about it. Hitler decides if you’re Jewish.” As I looked around the class I could feel myself stiffen. These kids looked like the enemies of my childhood. These were the faces of the Irish kids from The Incarnation School, who used to come around when we were gangs in Washington Heights to look for Jews to stomp. They sometimes called us Christ killers. Some of my first words to the Contemporary Literature class were as follows: “The only guy in this room who understands how I grew up is up there.” I pointed at the figure on the cross. Nobody laughed. I dropped it. I don’t know if anyone got it. They were kids. It probably was not funny.

My Notre Dame experience was pleasant enough. My relationships there felt more like family than they did at other places I worked. The faculty was lively and collegial. Father Hesburgh enfolded everything in a wide spread of his catholic cassock. Most everything was tolerated within his liberal purview. I had a budget to bring in some radical experimental writers, and often they would be entertained at the house of Digger Phelps, whose wife was getting her Master’s in English. Digger was taking the basketball team to the Final Four. It delighted my writer’s heart to hear the extreme avant-garde poet/composer, Jackson MacLow, discuss college recruiting shenanigans with the coach. The Sophomore Literary Festival was a great event, that brought in such eminences as Tennessee Williams, William Burroughs, and Ken Kesey. I taught tai chi there at a community center. A club called Vegetable Buddies brought in all the great blues singers and musicians from the South Side of Chicago. Chicago itself was only two hours away, and my son, Nikolai, was at the University of Chicago. I spent a lot of time with the lovely Jane Jensen of Mishawaka, whom I loved, but I understood that too late. I was too close to the confusion of my family break-up.

As my two-year stint came to an end, I received an official letter that I’d been considered for tenure, and turned down. I’d never thought about tenure, never applied. The letter went something like this: “Even if you weren’t a Jewish novelist we would not grant you tenure, because we do not want to tenure a novelist of any persuasion.” It was approximately that. I didn’t even get a chance to say, “But I like football.” I’d never thought about tenure. At the time I didn’t understand it, didn’t think I’d want it anywhere. Teaching was not something I saw myself doing forever. It wasn’t until several years later that I realized that the letter, which I immediately tore up and tossed, could probably have provided grounds for litigation, might have bought me a few years out of the yoke. I don’t litigate. Too dreary and time consuming. I’ll litigate only if litigated upon.

You have to accept the idea that subjective time

with its emphasis on the now has no objective

meaning… the distinction between past, present,

and future is only an illusion, however persistent.

Albert Einstein

I won’t write this. I can’t.

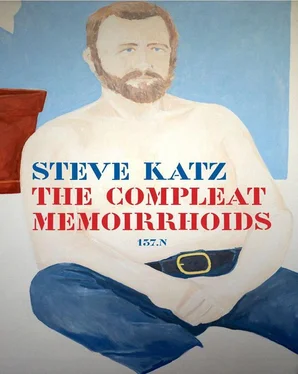

Before I started to produce the Memoirrhoids most of my works exercised in the grotesque, the perfectly bizarre, in erupted structures closer to the skin of my experience of the twentieth century. For me this was a more “realistic” evocation of what it felt like to be rattling around in our dystopia than anything I could ever leach from the modes of pedestrian realism that the American literary establishment embraced.

These Memoirrhoids are different. I’m looking to retrieve the past, to tell it like it was. Fat chance. I can’t write this. I can’t even establish NOW. When is it? To grab it is like trying to grip a handful of mercury. It squirts into the past as I back into the future. I never see what’s coming until it is NOW, and any NOW immediately takes its place in the reticulation of signs blinking out there that I scan as my past. Son of a bitch. There’s no way I’ll ever write this. I haven’t got the metaphysical chops. How do you describe, evoke; I mean, write any moment? The moment relentlessly disappears into language, a medium that obliterates as soon as it connects.

Читать дальше