Richard Ford - The Sportswriter

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Richard Ford - The Sportswriter» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1995, Издательство: Vintage Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

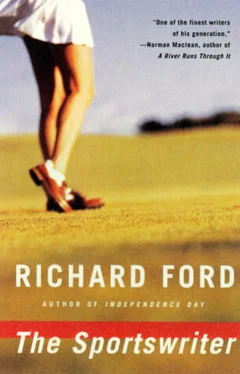

- Название:The Sportswriter

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1995

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sportswriter: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sportswriter»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sportswriter — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sportswriter», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Mine, I’m happy to say, is the best possible.

“Well, hey,” I say in a stirring voice, hands upon my breast. “What say we get out of here and take a walk? I haven’t eaten since lunch, and I could pretty much eat a lug wrench right now. I’ll buy you a sandwich.”

Catherine Flaherty bites a piece of her lip as she smiles a smile even bigger than mine and colors flower in her tulip cheeks. This is a pretty good idea, she means to say, full of sentiment. (Though she is already nodding a business woman’s agreement before she speaks.) “Sounds really great .” She flips her hair in a definitive way. “I guess I’m pretty hungry too. Just let me get my coat, and we’ll go for it.”

“It’s a deal,” I say.

I hear her feet slip-skip down the carpeted corridor, hear the door to the ladies’ sigh open, sigh back, bump shut (always the practical girl). And there is no nicer time on earth than now — everything in the offing, nothing gone wrong, all potential — the very polar opposite of how I felt driving home the other night, when everything was on the skids and nothing within a thousand kilometers worth anticipating. This is really all life is worth, when you come down to it.

The light across the street is off now. Though as I stand watching (my bum knee good as new), waiting for this irresistible, sentimental girl’s return, I can’t be certain that the man I saw there — the heavy man in his vest and tie, surprised by the sudden sound of a voice and his own name, a sound he didn’t expect — I can’t be certain he’s not there still, looking out over the night streets of a friendly town, alone. And I step closer to the glass and try to find him through the dark, stare hard, hoping for even an illusion of a face, of someone there watching me here. Far below I can sense the sound of cars and life in motion. Behind me I hear the door sigh closed again and footsteps coming. And I sense that it’s not possible to see there anymore, though my guess is no one’s watching me. No one’s noticed me standing here at all.

THE END

Life will always be without a natural, convincing closure. Except one.

Walter was buried in Coshocton, Ohio, on the very day I sounded the horns of my thirty-ninth birthday. I didn’t go to his funeral, though I almost did. (Carter Knott went.) In spite of everything, I could not feel that I had a place there. For a day or two he was kept over in Mangum & Gayden’s on Winthrop Street, where Ralph was four years ago, and then was driven back to the midwest by long-haul truck. It turns out it wasn’t his sister I saw on the train platform in Haddam that night, but some other woman. Walter’s sister, Joyce Ellen, is a heavy-set, bespectacled, YWCA-type who has never married and wears mannish suits and ties, is as nice a person as you will ever meet, and has never read Teddy Roosevelt’s Life . She and I had a long, friendly visit at a coffee shop in New York, where we talked about the letter Walter had left and about Walter in general. Joyce said he was a kind of enigma to her and her entire family, and that he hadn’t been in close touch with them for some time. Only in the last week of his life, she said, Walter had called up several times to talk about hunting and the possibility of moving back there and setting up a business and even about me, whom he described as his best friend. Joyce said she thought there was something very strange about her brother, and she wasn’t all that surprised when the call came in. “You can feel these things coming,” she said (though I do not agree). She said she hoped Yolanda wouldn’t come to the funeral, and I have a suspicion she got her wish.

Walter’s death, I suppose you could say, has had the effect on me that death means to have; of reminding me of my responsibility to a somewhat larger world. Though it came at a time when I didn’t much want to think about that, and I still don’t find it easy to accommodate and am not completely sure what I can do differently.

Walter’s story about a daughter born out of wedlock and grown up now in Florida was, it turns out, not true, but simply a gentle joke. He knew, I think, that I would never run the risk of letting him down, and he was right. I flew to Sarasota, did a good bit of sleuthing, including some calls about birth records in Coshocton, I called Joyce Ellen, even hired a detective who cost me a good bit of money but turned up nothing and no one. And I’ve decided that the whole goose chase was just his one last attempt at withholding full disclosure. A novelistic red herring. And I admire Walter for it, since for me such a gesture has the feel of secrecies, a quality Walter’s own life lacked, though he tried for it. I think that Walter might’ve even figured out something important before he turned the television on for the last time, though I wouldn’t want to try to speak for him. But you can easily believe that some private questions get answered — just in the nature of things — as you anticipate the hammer falling.

Coming to Florida has had a good effect on me, and I have stayed on these few months — it is now September — though I don’t think I will stay forever. Coming to the bottom of the country provokes a nice sensation, a tropical certainty that something will happen to you here. The whole place seems alive with modest hopes. People in Florida, I’ve discovered, are here to get away from things, to seek no end of life, and there is a crispness and a Tightness to most everyone I meet that I find likable. No one is trying to rook anybody else, as my mother used to say, and contrary to all reports. Many people are here from Michigan, the blue plates on their cars and pickups much in evidence. It is not like New Jersey, but it is not bad.

The time since last April has gone by fast, in an almost technicolor-telescopic way — much faster than I’m used to having it go — which may be Florida’s great virtue, instead of the warm weather: time goes by fast in a perfectly timeless way. Not a bit like Gotham, where you seem to feel every second you are alive, but somehow miss everything else.

With my bank savings, I have leased a sporty, sea-green Datsun on a closed-end basis and left my car and my house in Bosobolo’s care. This has allowed him — as he explained in a letter — to bring his wife over from Gabon and to live a real married life in America. I don’t know the fate of the dumpy white girl. Possibly he has put her aside, though possibly not. And neither do I know what my neighbors think of this new arrangement — seeing Bosobolo out in the yard, surveying the spirea and the hemlocks, stretching his long arms and yawning like a lord.

I have a furnished adults-only condo out on a pleasant enough beachy place called Longboat Key, and have taken a leave of indefinite absence from the magazine. And for these few months I’ve lived a life of agreeable miscellany. At night someone will often put on some Big Band or reggae records, and men and women will gather around the pool and mix up some drinks and dance and chitter-chat. There are, naturally, plenty of girls in bathing suits and sundresses, and once in a while one of them consents to spend a night with me, then drifts away the next day back to whatever interested her before: a job, another man, travel. A few agreeable homosexuals live here, as well as an abundance of retired Navy men — midwestern guys in most cases, some of them my age — with a lot of time and energy on their hands and not enough to do. The Navy men have stories about Vietnam and Korea that all together would make a good book. And one or two have asked me about writing their life stories once they learned I write for a living. Though when all that begins to bore me, or when I don’t feel up to it, I take a walk out to the water which is just beyond the retaining wall and hike a while in the late daylight, when the sky is truly high and white, and watch the horizon go dark toward Cuba, and the last tourist plane of the day angle up toward who knows where. I like the flat plexus of the Gulf, and the sensation that there is a vast, troubling landscape underwater all lost, with only the definite land remaining, a sad and flat and melancholy prairie that can be lonely but in an appealing way, I’ve even driven up to the Sunshine Skyway, where I have thought of Ida Simms, and of the night Walter and I talked about her and of how much she meant to him. I have wondered if she ever woke up there or in the Seychelles or some such place and went home to her family. Probably not.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sportswriter»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sportswriter» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sportswriter» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.