Maggie understands she is looking at two kids.

Their shirt is wide, aqua-green, with uneven shapes hidden beneath it. Down the center of the trunk, a ridge like the leading end of a wedge. An arm comes out on each side. They wear shorts with three legs, their outward facing legs very far from each other. Their middle leg has a gap above its knee where two thinner legs seem to separate like a cleft in the roots of a tree. Further down the leg, a second, smaller shoe hangs off the ankle at an angle, a baby boot, like a white rosebud or a hanging bell, resting limply on the larger, leather shoe. The other feet kick a little, like Maggie when she tries to swim, though more slowly, in coordinated circles.

“They share a little bit of brain,” explains Francine, speaking in English, “and some other organs. The doctors wanted to separate them, though the odds weren’t good they would live. They said it wasn’t worth living like this. I told them all to go to hell.”

Maggie nips her father’s hand because she wants to talk. He squeezes harder.

“These are the ones you were pregnant with when we left?” he says.

“They developed too quickly. They were born only a little after you left. The doctors were bewildered, though they said there had been a few cases that year. There haven’t been any since. They think maybe the Germans,” she trails off. “I don’t know. But we love them, don’t we?” She repeats it in French.

Albert says, “Of course.”

Dorian and Pierrot struggle to angle their eyes so they can see Maggie. They each have to gaze sidelong to look dead ahead. It makes her think of lizards. The one on the right closes his mouth. The one on the left says, “Hello.”

“Hello,” says Maggie’s dad. “I’m very pleased to meet you.”

“This is Uncle John,” says Francine.

“Hello,” says the one on the left. He reaches across himself to offer his hand. Maggie’s dad leans forward to shake it, finally releasing her mouth.

“Hello,” says her dad.

Dorian and Pierrot smile, closing their eyes in a way that says they feel happy. Then the one on the right—is he Pierrot?—begins to cry.

“They never feel the same thing at the same time,” says Francine. “Something about the brain parts they share. Only one of them ever gets to be happy. More and more often it’s Dorian. Pierrot is getting used to it.”

Cousin Matthew stands up. He goes for Pierrot’s hand. “It’s good to meet you,” he says. “You remind me of me. Maybe I can be your uncle.”

“Sure,” says Albert. “Uncle Matthew.”

Pierrot, holding Cousin Uncle Matthew’s hand, rolls his eyes up to look at his face, while Maggie’s dad continues to shake Dorian’s hand, and Dorian stares back at Maggie’s dad. Pierrot smiles. Dorian begins to weep.

“Good for Pierrot,” says Cousin Matthew.

“Too bad for Dorian,” says Maggie’s dad.

Soon the fifth kid is put back to bed. Maggie sees him three more times before the new family leaves. Pierrot never smiles again. Once, he looks very angry. Dorian is delighted.

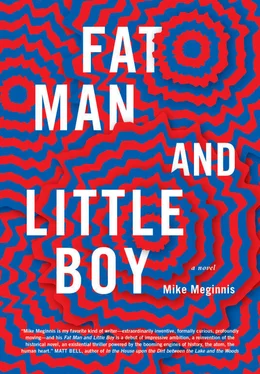

Picture Hollywood, summer 1956. The spindle palm trees with their leaves all shiver-shivering. All the highway tangles. Here are the beggars and the street performers—guitar, harmonica, kettle drum, saxophone, tap shoes—hats upside-down, weighed down with change and petty cash, sidewalks littered with cardboard fried chicken buckets, popsicle sticks or tongue depressors, chewing gum wrappers, cigarette butts with ash trail smears punctuated by dirt imprints of half a boot’s tread, tough guy toothpicks, and a part of somebody’s tire. Here’s the idling cop car parked up against the curb, right next to that fire hydrant. Maybe he’s getting his hair cut at the barber. Here are men and women, young and old, coming out of the barber’s, most of them sporting the same seven haircuts, and half the guys with Hawaiian shirts unbuttoned down the top third, curls of chest hair. If someone smokes a marijuana cigarette in an alley, leaning up against a dumpster, what they’re saying is leave me alone. If someone stands in that same alley though, just at the edge of the shadows, fluffing her bleached-blonde hair and waving a purple boa, wearing a pink polka-dot skirt with the hemline raised well past the point of modesty, clicking her heels on the pavement—if someone’s dressed like this and she blows a bubble of Doublemint, and she lets it pop so it hits her nose, and she sucks that back up in—then what she’s saying is don’t let me spend the night alone. Here’s the newcomer who has to learn to tell the difference, standing center-sidewalk, one hand on his gut, the other checking the umpteenth time for his wallet. His wife is at a shop window looking at exotic belts. His brother, his nephew, his son, Little Boy, is standing beside him, his daughter’s hand—Maggie’s—squeezed tight.

Little Boy says, “Don’t you dare leave my sight, Magnolia. Don’t you dare leave my sight.”

Fat Man says, “We should find somewhere to eat.”

Rosie says she isn’t hungry yet. She says they can wait to find somewhere nice.

“Do you know how long it’s been since I had a real American burger?” says Fat Man. Which is, implicitly, a lie—fact is he’s never had one. He adjusts his shirt.

Rosie says, “You like them?”

“What’s not to like?”

“Where do you want to go then?” says Rosie.

“What about there?” He points down another street, the word “BURGER” glowing red, though the rest of the sign is obscured. “Something-Burger,” he says. “Sounds great. It’s always the little places that blow your socks off with a sandwich.” He totters in the Something-Burger’s direction. “Come on,” he says. “I’m starved.”

A streetcar rolls by briskly. It is in fine condition. Everyone inside is alive. He remembers the ones that he saw in Japan, rolled over on their sides, warped and impacted, full of the dead. This one makes a cheerful chiming. A boy hangs off the back.

It’s been a month since Francine and Albert came to Hotel Gurs. Two weeks after they left for home, Francine called a nearby restaurant, offering the waiter who answered a small fortune if he would have Fat Man on the line the same time the next day. The hotel itself does not, of course, have phone service. Fat Man dreaded the call until it came. It was almost a relief to hear Francine’s voice, even as she delivered terrible news.

“The fake cops, Bruce and Rousseau, came with real cops,” she said. “They arrested Albert. Took him away. I’ve got no idea what the charges are, they wouldn’t explain it. They said they’d been watching us—that coming to see us again when they did, before we came down to the hotel, was a feint. They wanted to see what we’d do. They said we went running to you. They called you the mastermind. I don’t understand. They said it wasn’t about the Blanc woman anymore, it’s much more than that now. I think they’ll come for you next. They want to bring you in, I think. I think they’ll come very soon.” She cried into the phone. It made the line crackle. “He’ll probably look guilty if you run but at least I know he’s been a scum. You were always kind to me. I think you should leave the country for a while, until we can figure out what’s happening.”

“Shh,” said Fat Man. “Shh-shh-sh. Thank you for calling me. We’ll set all this right, I’m sure of it. We’ll do as you say. We’ll run. I won’t tell you where. That would just make things look worse than they already do.” He calmed and soothed her while the waiter, hoping to receive his money from the gentleman rather than through the post, listened with wide eyes and prying ears. Fat Man shot him several contemptuous glances, to which the waiter was either oblivious or inured.

Читать дальше