"The way they bloodied up the Living Room," Stoker said, "you'd have thought it was the Amphitheater!"

He had arrested them both and administered first aid; amnesty or no amnesty, he declared, he was fetching them to Main Detention, where he meant to stay himself until Rexford should sober up and go "back where he belongs." As for Anastasia, she might breed a barnful of billy-goat bastards for all he cared.

Leonid said flatly: "He cares."

"Yep," said Greene. "Anybody can see that."

Stoker responded with a jeer. "So there they sit, Goat-Boy: two blind bats! Are they passed or failed?"

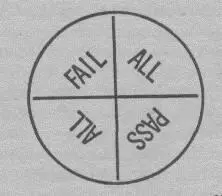

Affecting as the grim tale was despite its teller's sarcasm, and shocking the bloody sight of my former cellmates, I listened and looked without comment, if no longer without emotion. Yet it wasn't pity I felt, or terror, not even responsibility for their present wretchedness. Stoker's question had been mine since early on in his narrative, and had absorbed me entirely well before he asked it, fetching me from apathy into the intensest concentration of my life. Indeed, my spirit was seized: it was not I concentrating, but something concentrating upon me, taking me over, like the spasms of defecation or labor-pains. Leonid Andreich and Peter Greene — their estates were rather the occasion than the object of this concentration, whose real substance was the fundamental contradictions of failure and passage. Truly now those paradoxes became paroxysms: I shut my eyes, swayed on Croaker's shoulders, trembled and sweated. All things converged: I understood what I had done to Dr. Eierkopf with my innocent question about paleoooontological priority. That circular device on my Assignment-sheet —

beginningless, endless, infinite equivalence — constricted my reason like a torture-tool from the Age of Faith. Passage was Failure, and Failure Passage; yet Passage was Passage, Failure Failure! Equally true, none was the Answer; the two were not different, neither were they the same; and true and false, and same and different — unspeakable! Unnamable! Unimaginable! Surely my mind must crack!

"What is it?" Greene asked. "What's going on, Leo?"

"I can't see, classmate."

The troopers murmured at my strange countenance and behavior; Croaker rumbled, feeling my thigh-grip on his neck, and stood up in the sidecar.

"Don't try to get loose!" No doubt it was Leonid Stoker warned, but his words struck my heart, and I gave myself up utterly to that which bound, possessed, and bore me. I let go, I let all go; relief went through me like a purge. And as if in signal of my freedom, over the reaches of the campus the bells of Tower Clock suddenly rang out, somehow unjammed: their first full striking since the day I'd passed through Scrapegoat Grate. As all listened astonished, the strokes mounted — one, two, three, four — - each bringing from my pressed eyes the only tears they'd spilled since a fateful late-June morn many terms past, out in the barns. Sol, la, ti, each a tone higher than its predecessor, unbinding, releasing me — then do : my eyes were opened; I was delivered.

Dr. Eierkopf too the bells revived; at first sound of them he had sat up and clutched his head. On the sixth stroke he'd snatched off his new eyeglasses just in time, for the seventh shattered them, as earlier in the Belfry. On that eighth and last, blood spurted from his nose, his eyes rolled up out of sight, he shrieked, "Ach, mein Grunder, ist geborsten der Schädelknocken!" and collapsed again. Croaker bounded to his side, and I sprang down. The handcuffs fell at my feet.

"Halt!" a guard warned; Stoker drew his pistol. But I went in perfect sureness past him to the sidecar, and caught up his prisoners' hands.

"Leonid Andreich!" I said. "Pete! Thank you and pass you!"

"It is George," Greene said joyfully. "Hi there, George."

"Hi," I said. "Listen, Leonid: why are you going to Main Detention?"

"Because he's under arrest!" Stoker snapped.

Leonid shrugged. "I talk again to Dr. Spielman; maybe turn him looseness yet."

I gripped his hand. "Max doesn't want that, classmate. But you : look — " I tapped his handcuff. "You're free!"

He shook his head.

"Go back to Nikolay College!" I urged him. "That's where you have to pass!"

"Selfishly, George."

"Yes! And when you're passèd, try to help Classmate X."

"Forget it," Stoker said dryly. "This afternoon Chementinski declared himself a failure to the Union and asked for execution. Said he loved his son more than he loved the brotherhood of students. I imagine they'll oblige him."

"What is this!" Leonid cried.

"Never mind," I said. "Look: you and Pete have ended your quarrel. Re-defect! Tell your stepfather his confession was selfish: he wants them to kill him so he won't have to kill himself. Then tell him that's all right! Do you see?"

"George!" Leonid's forehead wrinkled above the bandage. "Passness of me, that's nothing! Even Classmate X, I love so, that's nothing to pass! But the self of Studentness — He matters! And you teach me He's flunkèd selfish! How He's pass?"

"Probably He can't," I said. "Try and see."

Red tears oozed into his bandage. "Failure is Passage, yes? No?"

I clapped him on the shoulder; the handcuff fell from his wrist.

"See here, now!" Stoker protested.

"Da!" Leonid cried. "Tomorrow, after Max: redefectness!"

"I'll take you to Founder's Hill," Peter Greene said, suddenly determined. "Look here: we'll meet my daughter at the Pedal Inn and stay the night; tomorrow we'll go to the Shafting together, for old Doc Spielman's sake."

"The flunk you will!" Stoker said. "You stay where you are!"

I took Greene's hand. "What then, Pete?"

He swallowed a number of times. "I got right smart of work to do back home, George. Finish up inventory; try and set things right with Sally Ann…"

"Do you really think your marriage can be saved?"

He set his chin, and would I think have blinked had his eyes been unbound. "Prob'ly not. But what the heck anyhow, George! I'm going to start from scratch, what I mean understanding-wise. Things look different to a fellow's been through what I been through. I got a long ways to go."

"Pass you!" I declared.

"Into first grade," he added wryly. "I might Graduate yet, one of these days. But the odds ain't much."

"They never are! Look for me at Founder's Hill tomorrow."

He now wept freely, and his wounded eye bled a little onto his cheeks. He supposed with a laugh that he'd have no more hallucinations, at least, and wondered aloud whether a mixture of blood and tears might be good for acne. "Come on," he said then to Leonid; "I'll show you the way to the Pedal Inn."

"Nyet, friend; I know the way. I show you."

"I'll show you both," I said; "I'm going back to Great Mall."

Stoker fired his pistol into the air. "Flunk all this! Who the Dunce do you think you are, Goat-Boy? The Grand Tutor Himself?"

I regarded him closely. "Have your men drive them to the Infirmary first and then to the Pedal Inn. If Dr. Eierkopf's all right, he and Croaker can wait in the Powerhouse until the Frumentians come tomorrow. Why don't you take me to Tower Hall yourself?"

"You're coming with me, all right," he said, "but not to Tower Hall! Get in that sidecar!" He commanded his men to ignore what I'd said; Greene and Leonid were to be delivered to the Infirmary for treatment of their wounds and then left at the Pedal Inn — but not at my direction, only because that had been his plan all along. The amnesty, he explained crossly, forbade him the use of Main Detention. Similarly, Croaker and Eierkopf (who was stirring now as his roommate licked his head) were to be taken to the Living Room, but purely because he, Stoker, hoped thereby to chase Rexford out; the guards were to see to it that Eierkopf directed Croaker to that end. As for me, if I thought he meant to chauffeur me to a tryst in the Belfry with his tramp of a wife, I had another think coming…

Читать дальше