I returned from the bathroom and, as I settled back into my chair, my friend pushed the paper napkin toward me.

You’re amused?

Give me the great illusion — I wait with bated breath, I said.

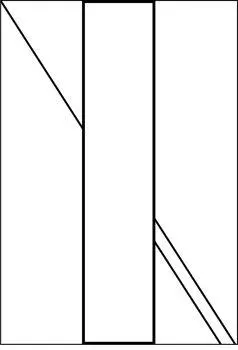

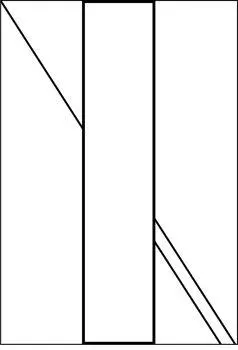

That’s good, he said. Now let’s begin with the obvious part, something we can agree on. This diagonal line on the left — which of the two diagonals on the right does it extend to?

The top one, I answered.

Of course it does, said Zafar. Now take this other napkin and line it up to check you’re right. Humor me.

I should have seen it coming. As I brought the edge of the folded napkin against the diagonal in the top left of the diagram, it became apparent that this line extended downward not to the top diagonal, as I had said, but to the bottom one.*

This is Poggendorff’s illusion, said Zafar. Johann Poggendorff, he continued, was a nineteenth-century German physicist and the creator of a number of measuring devices. Your father will probably have heard of him. There are countless optical illusions of a similar type — you probably know the Müller-Lyer illusion: two parallel lines with arrows at the end, arrows inverted on one of the lines; which line is longer?

I know that one, I said.

But it’s Poggendorff’s illusion I like the most, because it reminds me of the distinction between a reason for doing something and an incidental benefit of doing it. But I’ll come to that. You say that once we know how the world actually is — once we see it correctly — we can fix things. Now that you know what the truth here is, let me ask you one more time: Which of these two diagonals on the right, the top one or the bottom, which of them looks — and I mean looks —like it’s the extension of the diagonal on the left?

The same. Nothing’s changed, I replied. It looks the same as before.

Knowing how things are doesn’t make you see them correctly, doesn’t stop you from seeing things incorrectly. Stare at the image as much as you like, it’s all in vain. It will never surrender the truth, not to your naked eyes; you have to go in armed with a straightedge.

Yes, yes, I said, somewhat defensively — this was a human cognitive failing, everyone’s shortcoming, but I couldn’t help feeling that somehow I’d been shown up.

Do you know Harvard’s motto? he asked.

Veritas.

And Yale’s?

No, I don’t.

Lux et veritas. Light and truth. Quite a distinction. Shining a light doesn’t always reveal the truth of things. Jan Evangelista Purkyně said: Illusions of the senses tell us the truth about perception. * So the question is, he asked me: Do you trust your senses, your perception of the world?

Trust is a slippery word, I said. When I tell you that I trust someone or something, a newspaper or politician, say, I mean that his behavior agrees with my expectations of how he’ll behave.

Do you trust your own perception of the world?

Optical illusions aside, I think the way the world behaves tends to agree with my expectations of what it will deliver.

Aren’t you putting the cart before the horse?

How so?

Your expectations are formed by your perceptions in the first place. Then you use later perceptions to determine if your expectations have been met. What if your initial perceptions make you form stupid expectations? What if your own perceptions are rigging the game before it’s started?

And we’re all living in a matrix of illusion, like the movie?

I looked for a response, but he just smiled.

Maybe, I continued, not trust then but believe. Don’t we have to believe in our perceptions? I asked. We have to have some faith. What’s the alternative?

Do you have to believe in evolution if you reject creationism?

Doesn’t it follow? What’s the alternative?

Why not hold off having a belief? Why do you have to have a belief one way or the other?

I read somewhere about a survey, I said, showing that most people who said they believed in Darwinian evolution actually got its basic ideas completely wrong when they were quizzed about it.

Exactly. Those people, said Zafar, have rejected creationism and placed their faith in ideas that they mistakenly regard as Darwinian evolution. Aren’t they better off suspending belief altogether rather than clinging to false gods? They don’t even meet your test.

What test?

Why do they need Darwinian evolution in their lives — their warped notion of evolution, that is? Didn’t you say you need to believe your perceptions — you need to believe something?

* * *

That day, I forgot to remind Zafar that he said he’d explain why he liked Poggendorff’s illusion more than others. When I recently researched the illusion, I discovered something quite extraordinary, which I suspect he had probably had in mind even as he looked out the windows of the café at the Union Jack above the British Museum.

According to one authority, the British national flag was designed in such a way as to overcome the pitfall of Poggendorff’s illusion, whose effect was known even before the German physicist formalized it. Here, some say it has to do with fimbriation and rules of heraldic design, and perhaps this is what Zafar was hinting at when he mentioned the distinction between a reason for doing something and an incidental benefit of doing it. In any event, the optical illusion is countered in the Union Jack by displacing the red saltire of St. Patrick slightly so that each spoke of the saltire can at least look aligned with its opposite spoke on the other side of the Cross of St. George. Along the length of each spoke of St. Patrick’s Cross, only one half of the width (not length) of the spoke is included in the Union Jack.

The flag is surprising for another, related reason. I expect many people think, as I did, that the flag is symmetrical about the central vertical and horizontal axes: that the top half is a mirror image of the bottom and the left half of the right. In fact, this is not true. The lack of reflective symmetry is visible in the corners of the flag. At the top right corner, the red saltire of St. Patrick meets the northern edge of the flag. If the flag had reflective symmetry about the axis that runs from left to right through the middle, then the upper left arm of the red saltire of St. Patrick would also meet the edge of the flag on its northern side. But it doesn’t; it meets the western edge. (The only symmetry the flag has is 180-degree rotational symmetry about its center.)

As I say, Zafar mentioned none of this business about the Union Jack. Instead, he proceeded, in his odd way, to where he was heading that day. I see that now.

* * *

Do you love her?

Meena?

Who else?

I’m not sure, I said.

Of course you don’t. But it doesn’t matter, right?

What do you mean I don’t love her? I didn’t say that; I said I’m not sure.

Does it matter?

Does what matter?

Does it matter whether you love her?

It might help.

So you don’t love her, said Zafar.

I didn’t say that.

I had always suspected him of a capacity for cruelty. I think I know why Zafar was attractive to women. I think I know how he drew them. He invaded their private spaces; he asked direct questions, questions just shy of inappropriate. For instance, he asked Eva — the young woman in Central Park — about her hair. That in itself should have scared women off. But Zafar was also manipulative. He invaded a woman’s space, but he let her know — he helped her believe — that she was safe when he did so. There was the smile, but there was also the mere fact of asking a question. It gives the illusion of control to the person who can choose her answer. When I thought of Zafar like this, when I understood how his manipulation worked, it brought him down a peg; he didn’t seem quite so charming. Maybe he didn’t know what he was doing. Maybe it was just ingrown habit. But the fact that it’s so well learned makes it no less manipulative. In fact, as I reflect on this, it seems to me that he and Emily had that in common; they were both highly manipulative. They had applied their skills in different directions, quite obviously, but whatever Zafar might ultimately have thought about the ways the two of them had been unsuited to each other, in this one regard — their respective capacities to manipulate — they had been perfectly matched.

Читать дальше