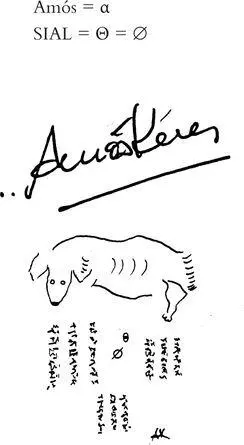

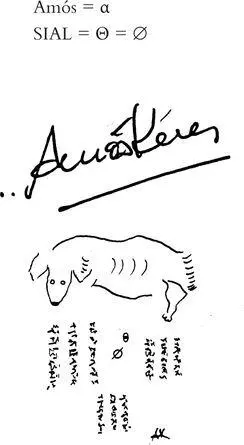

Amós Kéres, mathematician, doomed to the gallows for attempting suicide, justified in his view for having understood that the universe is the work of Evil and man its disciple, and then almost executed for trying to prove the logic of his understanding, was free. The scorched plain was here and there dotted with debris and mud and there was no sign of a single human on the landscape. Aching, he took two or three steps. Shouted ohs ahs, anybody out there, anyone there, hey world, hey storm! Since nobody answered in the course of many days and nights, he kept walking. In the direction of what? he thought at times. He’d have to see. As soon as he could see.

To think the great discomfort

Of feeling you here, in nausea, in excrement.

To think myself to myself, also the prison of your body

Stretched in the black branches of this night.

To think that I thought of you as a flash and rice paddies. Seed.

And sharp dyes

Returning to the crumbled walls. And that I thought of you

As though I had only seen you

In the abyss incarnate with infinite lives.

And to discover that your means

Are equal to the steps

Of drunkards.

That there is old age and death

In everything that you created: suns, galaxies. And in us:

Animals of your pasture.

Beyond the other side of the mirror: I, Amós, longer, thinner, walking to that tree where I’d intended to sleep my ten minutes. The tree seems to me like an old, wild fig tree, wide-leafed vines around its trunk. I saw three hundred yards away the gallows and the gibbet. A stumpy man, oval-headed, moved among the broken boards. He bellows: and doesn’t it seem that he’s right? Only the devil can unleash such a booming fury. And where are the patrols, the escorts, the doomed man himself? Well there you have it, whoever carries out the law is nearly buried alive, and where does that leave the one who breaks it, where is everyone? Where is he? I’ll look for him wherever he is, he must be hanged, dead or alive. The hangman shakes his whole body like a wet dog. He tramps across the ground, his boots high and tight. He cleans his hands, wiping them across his thighs, groin: well, that son of a bitch, he was going to be my tenth hanged man, after that it’s retirement, pension, I was going to raise some pretty pigs. After the tenth you’re done, the magistrate told me. And the tenth was this son of a bitch, this inventor of fears, this pimpled snotty knowitall. He should’ve shut up if he understood the world like that. I got my own ideas but who’s gonna listen to ’em? Not even a stone, because these ideas don’t leave my mouth. By keeping my mouth shut I still have my bread and butter, my life. I swallow everything I think. Well now. Will they hang the bishop, the Professor? I’m standing by. I never even spoke with any of the condemned. And I could talk to them, why not? They’d be shut up from then on, forever. But I’m cautious. Things can change from one moment to the next. Didn’t they just change? He takes a few steps through the rubble and thinks that later they’ll definitely come to make a bonfire of the whole field, later he’ll definitely come across some other people and he’ll speak with the magistrate. Because he fulfilled his duty and understands it’s not his fault the escorts were negligent with their escorting, it’s not his fault if God or the devil spewed wind and water to bring everything down. After the tenth hanged man you’re done, he remembered very well what the magistrate said. He’d get the runaround, they’re going to tell him that there’s no hanged man without a wrung neck. Well, they’ll see, I’ll find that blabbermouth, that blather-world and dead or alive I’ll get him in the noose.

Blind I will walk over hot coals

Mangled and demented for all

But a trilling troubadour

Of the black paradise of your face

Or if you like, fold me.

Your hand on the back of my head

Will curve my body down to the waist

In the barrels of the question. I must know the pit

Of never understanding. As they have been until now

Over me, these sandy winds of your breath

Or quiet me. My heart joined to the moss of the stone

Exempted from this search.

I do a few somersaults. Mirror and boots. I’m a castaway from myself and a gardener. I’m in the depths but I plant as though I were outside. I’m an executioner in a classroom. If they ask me I don’t respond. This is who I am. Somersault, cuddle, fish, silken tail, water, grindstone clouds in this aquarium. The eyes eye me. The faces lean their noses into my space. Mutely I roam through the room. There is a circle of glass between us. There are a bunch of people in the entryway: is that the professor? Begonia. I revisit the window in its yellows. We are questions in an extensive and inconclusive ball of twine.

I lie down on the thread, the twine nestles me, it goes concave, gets longer, makes a hammock, I sleep hearing groans and complaints. The ones who can see me are very annoyed. A man crosses the room, sits down, farts on my black chair. I ask: did you say your name, sir? There are laughs from the desks in the back. Someone gives me a jasmine. I am mutely bored. The questions grow and form cubes in the air. They collide. I stretch out on the smoothness of the mats. A cube wounds my worn-out elbow. Another bangs against my forehead, testing my bone brown with shackles. Women invade the room. They stomp on me with their high heels. Sado-slippery I’m sweating and laughing. Grotesquely I’m dispersing. There’s blood spattering the walls of the circle. An avalanche of cubes blankets my tissues of flesh. I’m empty of anything good. Full of the absurd.

Lift me, Shining One

To the opulence of your shoulder.

With my dog-eyes I stop before the sea. Tremulous and sick. Bent, thin, I smell fish in the driftwood. Fishbone. Tail. I gaze at the sea but don’t know its name. I remain standing there, askance, and what I feel is also nameless. I feel my dog body. I don’t know the world, nor the sea in front of me. I lie down because my dog body orders it. There’s a bark in my throat, a gentle howl. I try to expel it but man-dog I know that I’m dying and I will never be heard. Now I’m a spirit. I’m free and fly over my miserable being, my abandonment, the nothing that contains me and that made me on Earth. I am rising, wet like fog.

The snares: As if a dead man

Believed the sunflower of life

To grow upon his chest.

Amós Kéres, 48 years old, mathematician, was nowhere to be seen. In the arbor, the she-dog looked to the sky, sniffing. His mother found a phrase on paper: God? a Surface of Ice Anchored to Laughter. And below it:

this page Ernest Becker (1927–1974) was a Jewish American cultural anthropologist and author of Denial of Death (1973), one of Hilst’s favorite books. She dedicated several of her books to him. José Antônio de Almeida Prado (1943–2010) was a composer and pianist. Mário Schenberg (1914–1990) was a theoretical physicist. Newton Bernardes (1931–2007) was a physicist. Ubiratàn d’Ambrosio (b. 1932) is a mathematician.

this page This translation of Copernicus appears in Arthur Koestler’s The Sleepwalkers , a book Hilst had in her library in Portuguese translation. Koestler is probably responsible for the translation from German to English, which is used here; in The Sleepwalkers , he was citing the book Entstehung und Ausbreitung der Copernicanischen Lehre (Erlangen, 1943).

this page Georges Bataille, Inner Experience , trans. Leslie Anne Boldt (Albany: SUNY Press, 1988), 13.

Читать дальше