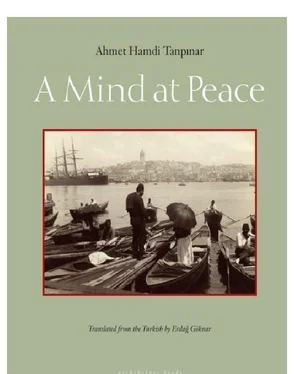

Behçet had loved, and was jealous of, Atiye, his own wife of twenty years. First he grew jealous of her, then of Dr. Refik, one of the first members of the Committee of Union and Progress, and as a result, he made an illicit denunciation of Dr. Refik through a secret police report to the Ottoman palace; but even after the doctor’s death in exile, Behçet couldn’t save himself from fits of jealousy. As he’d told İhsan himself, when he heard the lady softly singing the “Song in Mahur” on her deathbed, he struck her in the mouth several times, and thereby had maybe hastened her death. This particular “Song in Mahur” was a ballad by Nuran’s great-grandfather Talât. The ordeal and many like it had given Behçet the reputation of being bad luck by several factions in their old Tanzimat-era family, which had flourished through a series of well-arranged marriages. Yet, the haunting ballad remained in people’s memories.

The “Song in Mahur,” in its simplest and shortest version, resembled a visceral cry of anguish. The story of the song was strange in itself. When Talât’s wife, Nurhayat, eloped with an Egyptian major, Talât, a devotee of the Mevlevî order, had written the lyrics. He’d actually wanted to compose a complete cycle of pieces in the same Mahur mode. But just at that time, a friend returning from Egypt informed him of Nurhayat’s death. Later he learned that her death coincided with the night he’d finished composing the piece. In Mümtaz’s opinion, “Song in Mahur,” like some of Dede Efendi’s compositions and traditional semâi songs or like Tab’î Efendi’s “Beyâtî Yürük Semâi,” was a piece with a distinctive rhythm that confronted the listener with fate in its profundity. He distinctly remembered when he’d heard Nuran sing the song and tell the story of her grandmother. They were on the hills above Çengelköy, a little beyond the observatory. Massive cumuli filled the sky and the evening descended like a golden marsh over the city. For a long time Mümtaz couldn’t determine whether the hüzün of inexplicable melancholy falling about them and the memory-hued twilight had emanated from the evening or from the song itself.

Behçet replaced the cane handle. Yet he couldn’t pull himself away from the folding fan. Obviously the small feminine accessory cast him — a man whose entire intellectual life had frozen like clockwork stuck at his wife’s death, and who resembled a living memento from 1909 in his outfit, necktie, and suede shoes — far back into time, to the years when he was the fine gentleman Behçet, when he was enamored and grew jealous of his beloved, and, not least of all, when he’d been the catalyst of her and her lover’s deaths. Presently, reminiscences long forgotten were being resurrected in the head of this living, breathing remnant of things past. I wonder which of life’s fragments he sees in these paving stones he stares at so intently?

An old shrew struggled to follow behind the used mattresses she’d purchased, perhaps up the street. The street porter she’d hired was overwhelmed by the top-heaviness of the burden on his back more than the weight itself. Mümtaz didn’t want to spend another second here; today neither the book market nor the Çadırcılar street market was of any consequence. He turned into the flea market.

The market was cold, crowded, and cacophonous. Almost everywhere in the small shops hung an array of clothing, prepared life-molds, like selfcontained fates. Buy one, put it on, and exit as a new person! Crammed on both sides were dresses, yellow and navy blue worker’s overalls, old outfits, light-colored summer wear whose tacking was visible above the sewingmachine seams, cheap women’s overcoats that sheared dreams of life to zero with unseen scissors from where they hung. They were displayed by the dozens on tables, small chairs, couches, and shelves. A cornucopia! No shortage of thrift and misery as one might have thought; just disrobe from life but once and be certain to find desperation in every imaginable size!

He stopped short before a display window: A small, broken mannequin had been dressed in a wedding gown that had somehow slipped down too far; on the bareness of her neck, above the décolleté, the shopkeeper had pasted the image of a betrothed couple cut from a fashion magazine. The prim and stylish couple, located under hair tinsel and veil and above the white gown, before a landscape fit for silver-screen lovers, made this watershed moment bursting with bliss an advertisement for life and love that subdued one like a season — as would happen in the mind of the woman who might wear this gown. A small electric bulb burned over this contentment-on-sale, as if to clearly emphasize the difference between thought and experience. With no need to look any longer, Mümtaz began to walk briskly. He made a series of turns and crossed a number of intersections. He wasn’t looking anymore; he knew what to expect. After having seen what rests inside me. For months now, everywhere, he’d seen only what existed inside him. And he realized, as well, that there was nothing so surprising or fearful in whatever he saw or stood before.

The market was a fragment of this city’s life; forever and a day it would confide in him somehow. All the same, what affected Mümtaz was not what he saw but rather his own life experiences.

Had he found himself before a good canvas by Pierre Bonnard, one of Les Nabis, or had he gazed at the Bosphorus from atop the Beylerbeyi Palace; had he listened to a piece of music by Tab’î Mustafa Efendi or to The Magic Flute, which he so admired, he’d still have these same feelings. His mind resembled a small dynamo stamping everything that passed beneath its cylinder with his own shape and essence, thereby obscuring and disposing of its actual meaning and form. Mümtaz had termed this phenomenon “cold print.”

Mümtaz’s relations with the external world had been this way for months. He perceived everything only after it had passed through the animosity between him and Nuran, spoiling its mood, coloring, and character. His person had been secretly contaminated, and he related to his surroundings only in accordance with the changing effects of the poison.

It might be a crisis eliding everything at a single stroke, like Istanbul’s rainy and misty mornings that deadened all color. No matter how much Mümtaz struggled to draw open the multilayered shroud, he’d fail to see anything familiar. Beginning with the consciousness of his existence, ashen muck, like a river whose flow was barely detectable, would carry everything away; a kind of Pompeii buried beneath lava and moving at the rate of a life span.

At such times nothing “good,” “bad,” “pretty,” or “ugly” existed for Mümtaz. Through an effectively isolated eye whose connection with the nervous system that sustained it had been lost and whose potential for analysis had been interrupted, an objective eye experiencing final moments of hermetic perception, Mümtaz would stare dumbly at the living visions in this garden of death, and at everything that broke free from the ashen muck and accosted him, as if he were staring at reflections of a realm of nothing but echo and aftershock.

At times, seized by an anxiety that shook the entire framework, rattling everything from the windows to the foundation, Mümtaz would be agitated by all things in a frenzy that pushed the limits of his mental faculties. No accident at sea could damage a ship on the verge of sinking down to the last stave, dislodging its every nail.

He turned toward the old Bedesten of the Grand Bazaar. The auction hall was empty. But the double-sided display cases and the rooms had been prepared for tomorrow’s great auction. In one of the cases, a single antique piece of jewelry, rumors of which had spread through Istanbul for the past two months, glimmered like a cluster of stars, rawly and savagely, yet not without beauty.

Читать дальше

![Джон Харгрейв - Mind Hacking [How to Change Your Mind for Good in 21 Days]](/books/404192/dzhon-hargrejv-mind-hacking-how-to-change-your-min-thumb.webp)